In the aftermath of the First World War, large areas of northeast France were left in ruin. Years of constant siege warfare along the Western Front had reduced buildings to rubble, churned countryside into a quagmire, and left the land littered with unexploded ordnance. From this ruin was born the Zone Rouge, or Red Zone – an area still too dangerous to live in a hundred years later.

The Problem

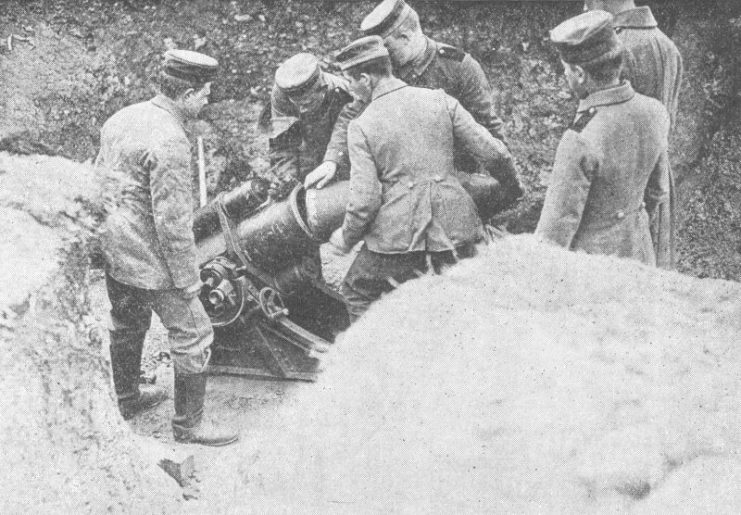

The fighting on the Western Front of World War One was unprecedented in its destruction. For four years, millions of men fought over the same patch of ground. The weapons they used, including vast batteries of heavy artillery and huge explosive charges placed in underground mines, reduced whole regions to nothing but rubble and craters. Communities were driven from their homes by the war, and the towns they left behind were turned into ruins.

In the aftermath, the French and Belgian governments found that they faced a serious challenge dealing with this land. If it had just been a matter of ruin, then they could have repopulated and rebuilt. But along the most fiercely contested sectors, the land was far too dangerous for that.

There were two problems – one obvious, the other more insidious.

The first was the unexploded munitions. Many of the explosives used during the war hadn’t gone off but still lay in wait, ready to kill or maim the unwary. In some cases, as when mines were laid, this was a deliberate feature of the weapon, but one the military leaders were willing to accept if it helped them win the war. In other cases, it was accidental, the result of faulty shells and grenades. Just because a munition didn’t go off when it was fired didn’t mean it couldn’t still explode years later.

The second problem was poisoning. Both sides used chemical weapons in the war, and this use left toxic residues in the soil. The rusting remains of buried battlefield debris added to the toxicity of the land, as lead, mercury, and zinc started to seep into the soil. In the worst cases, the poisons could quickly kill a human being. Even in less extreme areas, they could prevent plants from growing or make the crops deadly if eaten.

A Land of Ghosts

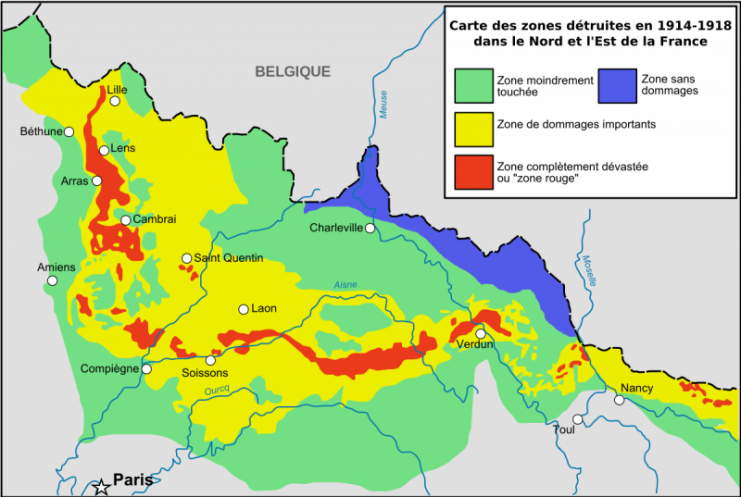

To deal with this, the governments mapped out the battlefields and marked off areas that were not safe for human habitation. A hundred years later, these divisions are still in place.

In France, this territory was divided into four zones, from the most deadly to those with no damage – red, yellow, green, and blue. The red zone consisted of areas of total destruction. 100% of the agriculture and buildings in this area had been destroyed. It had been left too deadly for human life. No-one was allowed to live on this land. In many areas, this is still the case.

The result was a strange and empty region, haunted by the remnants of the past. The ruins of devastated towns and villages could be found amid the rubble. In some places, so little remains that there is only a sign commemorating where a settlement once stood. These are the ghosts of once vibrant communities torn apart by war.

The war that destroyed them still haunts this place. The overgrown remains of trench lines, the remains of bunkers, rusted tanks poking out of the mud that swallowed them.

Nature Finds a Way

Despite the man-made ruin, nature has found a way to thrive amid the devastation of the red zone. To the surprise of early observers, plants quickly began to grow amid the toxic ruins. Grass and creepers overran the trench lines and heaps of rubble. Trees sprang up between them. Lush greenery took hold where, for four long years, there had been nothing but mud and destruction.

Then came the animal life. Snails, voles, and mice, too small to detonate the explosives, found a safe space to live. Wildcats came to prey on them. Deer and boar found shelter beneath the shade of sturdy juniper trees.

It isn’t a healthy place to live for some of these creatures. Explosives still create the risk of sudden death, and the larger animals are susceptible to lead poisoning as battlefield remains infect the food chain. But with so little human activity, it has become a paradoxically safe, quiet place, a rare and curious patch of wilderness in densely populated northwest Europe.

Reclaiming the Land

Humanity is also working to reclaim what was lost.

Some of this activity is symbolic. Signs have been put up to commemorate lost communities. The descendants of some of them still elect mayors for the lost towns, even though they are now scattered, far from the place their ancestors called home.

Some of it is far more practical. After a century of work, ordnance disposal experts are still laboring amid the ruins of the Western Front, identifying and safely disposing of explosives. Each year, they dig up 900 tons of explosive devices in France and another 200 tons in Belgium. Slowly, they are making the red zone safe again, but none of them will live to see the work complete. According to the agency in charge of the work, it will take at least 700 years to clear the dangers. Other people believe that it will never happen, that the scattered shells and landmines cannot all be found, and that this will never be a safe place again.

In the yellow and green zones, life has returned but is still affected by the war. Farmers have to have their crops tested for toxicity before they can sell them. Every year, they find more munitions beneath their fields, known as the iron harvest. In most cases, these are retrieved intact and taken to official dumping grounds. Sometimes a shell goes off and a farmer loses his tractor or just gets away with his life.

For the soldiers and politicians, the destruction of the First World War ended a hundred years ago. But in the red zone, it continues and will do so for centuries to come.