For the French, the First World War was about more than stopping an aggressive nation. The Germans had invaded north-eastern France and held land there throughout the war. French politicians and generals were eager to drive them out.

Partly because of this and partly because of strategic and tactical doctrine, the Allies launched a series of huge offensives over the course of the war, each one intended to break the German lines and bring a decisive victory. It was one of these offensives that triggered the Third Battle of Artois.

The Autumn Offensive

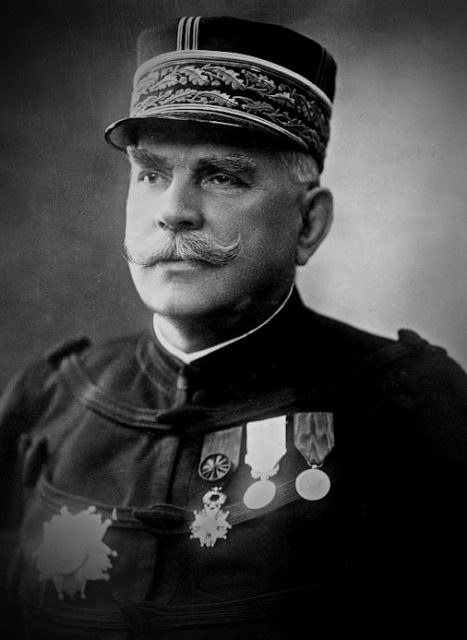

The Third Battle of Artois was part of a great offensive planned by Marshal Joseph Joffre, the French Commander-in-Chief, for the autumn of 1915.

Joffre’s plan was for two attacks at the same time. While the French launched an advance in the Champagne region, an Anglo-French force would attack the Germans in north-east Artois.

As always, the thinking behind the offensive was simple. By sheer weight of men and firepower, Joffre hoped to expend German resources in the region and break through their lines. By breaking through in Artois and Champagne, he could capture strategically important railways and force the Germans to abandon the Noyon salient, bringing about a substantial shift in the fortunes of the war.

Artois

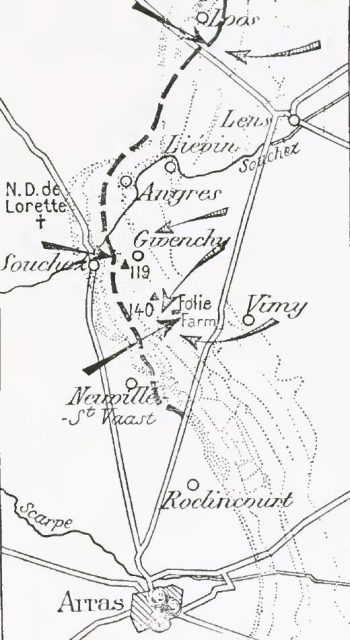

The Third Battle of Artois, also known as the Loos-Artois offensive, involved a pincer movement. French troops would seize the Vimy Ridge, vital high ground overlooking the flatlands around Arras. Meanwhile, to the north, the British would advance on the town of Loos.

Vimy Ridge

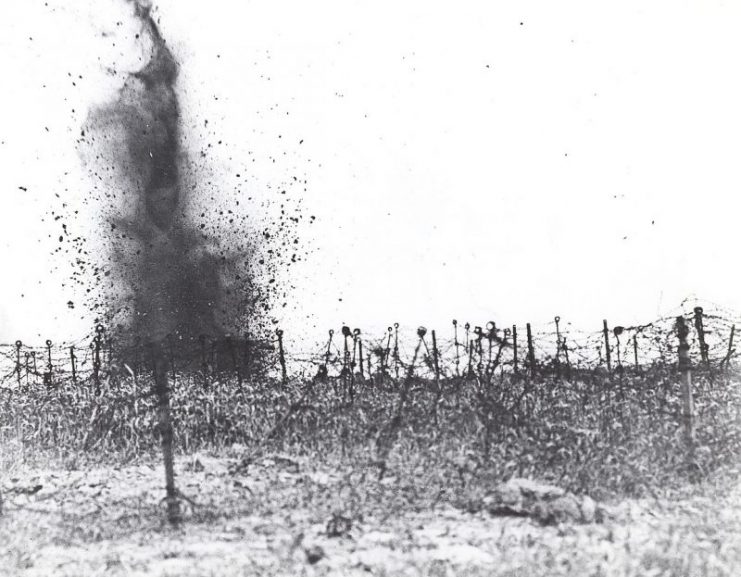

As usual with the offensives on the Western Front of World War One, the fighting at Vimy Ridge was preceded by a fearsome bombardment. From the 21st of September, Allied artillery pounded the German positions. Germans took shelter deep in their dugouts and waited for the rain of shells to end.

On the 25th of September, the shelling stopped. Nineteen divisions of the French Tenth Army, led by General Dubail, waited until after midday for the mist to clear. Then they advanced up Vimy Ridge.

The Germans had built an impressive defensive system on Vimy Ridge. Here, trenches and dugouts lay behind vast swathes of barbed wire, intended to obstruct opposing troops and entangle them within range of the German soldiers.

The defenses were manned by thirteen divisions of Crown Prince Rupprecht’s Sixth Army. As soon as the shelling stopped, they emerged from their dugouts and took up positions along the fighting line. Machineguns returned to their firing pits, rifles were readied, and behind the lines, artillery was loaded for action.

A successful attack against these positions relied on several factors, and one of the most critical was the artillery bombardment. More than one and a half million rounds had been thrown against the Germans during the preparatory bombardment.

For the infantry to get through, they needed to cut the wire and smash open the German defensive positions. The artillery would then turn its attention to counter-battery fire against the German guns, to keep them from bombarding the French infantry.

As the French troops approached the German lines, it became clear that the bombardment had not achieved its goals. Much of the barbed wire was still intact, as were many of the defensive positions beyond it. The German soldiers, who theoretically should have been battered almost into submission, were standing ready to fight.

The result was very high casualties on the French side, in return for limited gains. The 29th division continued to fight its way through the layers of German defenses and reach the top of the ridge. However, the Germans retook the highest ground, robbing the French of the advantage they had sought. French troops never broke through the rear lines of the German defenses.

Fighting continued into October as autumn rains fell and the troops sank into exhaustion. Meanwhile, the need for shells at Champagne deprived the offensive of much-needed supplies.

Loos

Like the French, the British bombarded the German forces in their sector before launching an assault on the 25th.

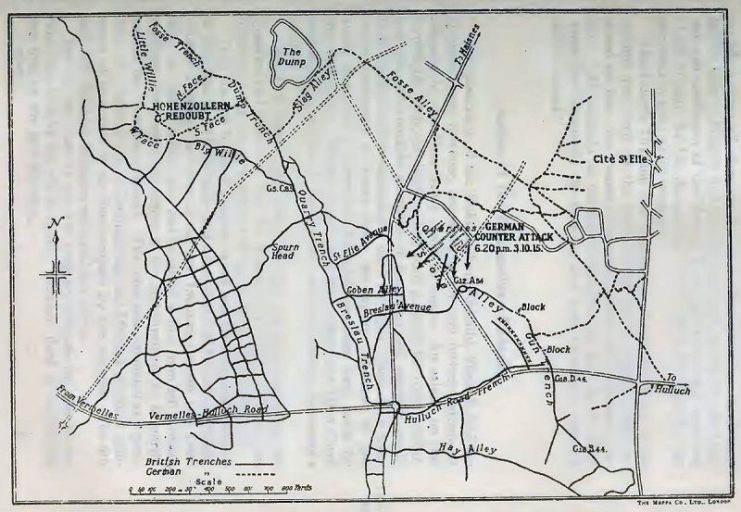

Six divisions of the First Army, commanded by General Douglas Haig, launched themselves against outnumbered Germans. A shell shortage hindered the effectiveness of the British artillery, and the British faced many of the same problems as the French – uncut wire, large areas of unbroken defenses, and German troops pouring out straight after the bombardment to man the guns.

Despite this, the British were initially successful. They captured the town of Loos.

But then the problems began. Field Marshal John French, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, withheld the reserves that Haig needed. There was trouble getting supplies through to the units on the newly advanced front.

Then came a German counter-attack, driving the British out of their recently taken positions. The fighting swayed back and forth, with high casualties on both sides. The Germans retook defenses they had abandoned, while many British troops found themselves back at their starting positions.

The fighting continued into October, while rain arrived and the men became exhausted and demoralized.

End

By the middle of October, both offensives had effectively ground to a halt. The Third Battle of Artois theoretically continued into early November before being called off.

The French and British had suffered a total of 108,000 casualties between them. The Germans lost less than half that number, thanks to the advantage of fighting from defended positions. Little ground changed hands.

In the aftermath, Field Marshal French was dismissed from his position in charge of the BEF. Already struggling to cooperate with Britain’s allies, he had further undermined the situation by his mismanagement of the Battle of Loos. His credibility shredded, he was removed from command. Haig, a commander who had struggled to succeed under him, took his place.