The Battle of Gallipoli was an especially brutal campaign that took place over eight months during 1915-1916. It made heroes of many men, but William Dunstan was one of those who really stood out.

When nearly half a million soldiers are killed on both sides, it becomes difficult to separate the individual from the cold statistics of carnage. But when anyone is awarded a Victoria Cross, they instantly stand out from the crowd. It’s always remarkable when a person can undertake such acts of selfless valiance, live to tell the tale and continue to have a full life – but that’s exactly what Dunstan was able to accomplish.

On the Allied side, there were around 252,000 casualties among ANZAC, French and British forces, while the Ottomans and Germans had between 218,000-251,000 deaths. The aim of the Gallipoli landings was to secure the sea passage to the Russian Empire, an ally to those fighting the Germans during the campaign.

Allied commanders wanted to secure the peninsula and march on Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), which was the capital of the Ottoman Empire. The reverberations of that failure were felt around the globe – leading to ANZAC day in Australia and New Zealand as well as the birth of an entirely new nation, Turkey.

But for Dunstan himself, the military disaster would have a different meaning. The soldier was born in Ballarat, Victoria, Australia in March 1895 and was the third son of William John Dunstan and his wife, Henrietta.

He attended the Golden Point State School and was said to be a bright pupil. At the age of 15, Dunstan left school to begin working as drapery store clerk. Dunstan joined the army as part of the compulsory training scheme, where he rose to the cadet rank of Captain. In July 1914 he was commissioned as a Lieutenant in the militia.

In July 1915 the medal winner enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force as a Private. Two weeks later Dunstan embarked for Egypt with the role of acting Sergeant of the 6th Reinforcements of the 7th Battalion.

From August he was made an acting corporal with the 7th Battalion and was transferred to Gallipoli, where he began fighting in the Battle of Lone Pine. This area of fighting was named after the one Turkish pine tree that stood in the location before the fighting began. The battle took place between the 6th and the 10th of August 1915.

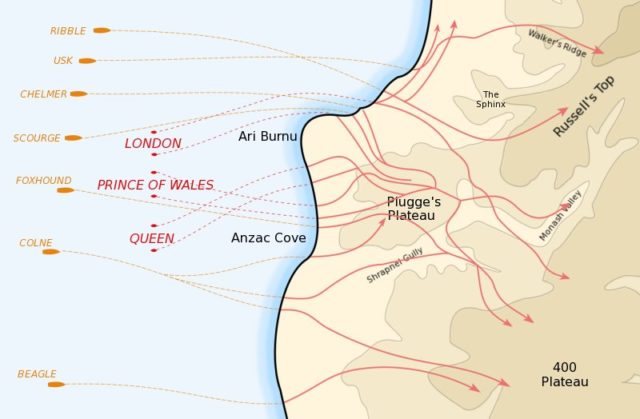

Australian forces launched an attack with the plan of drawing Ottoman attention away from several key assaults on Sari Bair, Hill 971 and Chunuk Bair. The attacking forces began assaulting the position, which was of strategic importance, with Brigade strength and captured the Ottoman trench line during the first few hours of fighting – but that wasn’t the end of the engagement.

Not to be defeated so easily, the Ottoman defenders launched numerous counter-attacks to try and make up the ground they had lost, which is where Dunstan won his Victoria Cross.

Just three days after the start of the offensive and just over two months after enlisting, Dunston committed the acts of courage and steadfastness under enemy assault that would earn him his Victoria Cross. It was the 9th of August, 1915. Dunstan was just 20 years old and was occupying a newly captured Ottoman trench along with Lieutenant Frederick Tubb, Corporal Alexander Burton, and ten other men. The Turkish forces launched a ferocious counter-attack, and the 13 were tasked with holding them off.

The attack was carnage, and two soldiers were blown to smithereens when they were tasked with throwing back grenades that were lobbed into the trench, or smothering them with their overcoats.

The remaining 11 looked to have things under some form of control when the attackers launched several bombs into the trench and killed or wounded five more men. Suddenly the defenders had gone from double to single figures, and their chances of survival had dropped like a trench coat trying to smother a grenade.

Tubb, Burton and Dunstan continued to fight on, they had to; they were the only men able to. Then another explosion blew down the barricade – their only protection. Tubb then drove off the Turkish forces while his comrades Dunstan and Burton set about the dangerous work of rebuilding the barricade. Upon seeing this, the Ottomans attacked again and again, but again and again, Dunstan rebuilt the barricade while Burton was lying dead on the floor.

At the end of this phase of the battle, Tubb was wounded in the head and the arm while Dunstan was blinded by a gunshot wound to the face and eyes. He was admitted to the 1st Australian Casualty Clearing Station on the 9th of August – and from there on to the 15th General Hospital in Alexandria. From then on, Dunstan returned home and was discharged on the 1st of February, 1916. In an absolutely remarkable three months, he’d seen one battle, won a Victoria Cross and been medically discharged after his heroic actions on foreign soil.

The outcome of the battle was a victory for the Australian forces, with the fighting being the some of the fiercest that they had experienced up to that point. Much of it took place in sweaty, dark and crowded trenches with grenades and bayonets. Despite the localised fighting on Lone Pine being a victory for the Allies, the wider August Offensive failed and resulted in a grinding and meaningless stalemate that ultimately lead to the evacuation of Gallipoli in December 1915.

Back home, on the 9th of November, 1918 Dunstan married Marjorie Lillian Stewart Carnell in his hometown of Ballarat, Australia. The couple had three children, one daughter and two sons, all of whom served in World War Two. The VC winner then moved to Melbourne, where he worked in the Repatriation Department. In 1921, Dunstan joined the Herald and Weekly Times as an accountant and worked his way up to become General Manager in 1934.

The heroic soldier’s life came to a swift and sad end on the 2nd of March, 1957, when he died of a sudden heart affliction. He was survived by his wife and children, while 800 people and seven VC winners attended his funeral.