There are many unflattering labels to apply to the disastrous events in the North Sea early in the morning of September 22nd, 1914. Certainly, for the British Royal Navy, it was a huge waste of life, an embarrassment, both nationally and internationally, and a deeply foolish mistake.

As the three Royal Navy cruisers sunk into the cold waters a few miles off the coast of the Netherlands. They were torpedoed by a single German U-boat and the day could be called the beginning of an era, an important wake-up call, and a major lesson to both Germany and Britain on what modern naval warfare had become.

Barely a month into the First World War, the great naval powers of Britain and Germany had yet to understand the role submarines could play. Indeed, after their first few engagements (though both Germany and Britain sunk a light cruiser in the first few weeks of war with submarines), not all naval authorities were convinced that they were particularly useful in comparison to their top-side counterparts like behemoth Dreadnaught Class battleships.

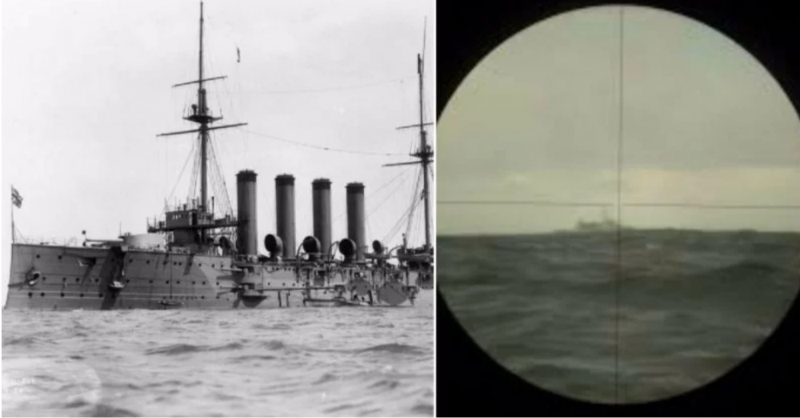

With such a mindset, three British armoured light cruisers, HMS Aboukir, HMS Hogue, and HMS Cressy, were sailing almost straight abreast, two miles from each other, and riding straight ahead through the North Sea. No zigzagging or precautions were being taken as it was figured that the turbulent seas of a few hours earlier, which had been too rough for the destroyers assigned to patrol a different approach to the English Channel, must have also been too rough for submarines.

Captain John Drummond of the Aboukir was assigned to lead the squadron in the absence of Rear Admiral Arthur Christian. His flagship HMS Euryalus had to return to port at 6:00 AM for coaling and communications issues. Though dimwitted in regards to the threat of German U-boats, he was far down the list of people who should have taken action to avoid the coming catastrophe.

This particular squadron was formed of Bacchante or Cressy Class armoured cruisers, which had been built right around the turn of the century and were considered quite unreliable and obsolete. The men who were assigned to operate them were pulled in from the reserves as WWI began. There were also many Naval College cadets onboard the vessels, often younger than 15 years old.

Several of the Royal Navy’s admirals, commodores, and even the First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill had argued that such a squadron was at huge risk and shouldn’t be patrolling the North Sea. In fact, it had been nicknamed the “Livebait Squadron.”

However, Vice Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee, though aware of the Bacchante cruisers’ inadequacy, insisted that the squadron remain in their service until the new Arethusa Class cruisers had been completed.

It just shows how utterly without imagination the majority of our senior officers are.

–Lieutenant Sir Bertram Ramsay, who would go on to be an Admiral and great WWII officer

So the Livebait Squadron remained on patrol in the Broad Fourteens, the area of the North Sea West of the Netherlands which is characterized by its mostly consistent depth of 14 fathoms. And at 6:30 AM on the 22nd of September, a quiet beast struck from below.

For Kapitänleutnan Otto Weddigen, the fish were in the barrel. He had been hunting these waters for just such a catch as these three cruisers in command of his Type U 9 U-Boat, christened the SM U-9.

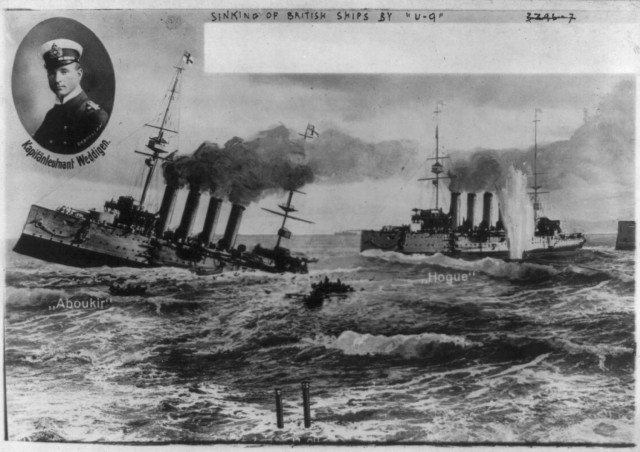

U-9’s torpedo tore into the Aboukir. Drummond assumed he had hit a mine and signaled the other two ships for help. According to Weddington, he must have hit under the magazine and the ship again shook from a massive explosion as this was set ablaze before going down at 6:55.

As the Hogue steamed in to pick up survivors, Weddigen fired his torpedoes again from just 300 yards away, striking the ship as the Aboukir fell beneath the waves.

The third of the Livebait Squadron ships lived up to its name, arriving to help the survivors of her fallen sisters. The Cressy was torpedoed at 7:20 and 7:30. None of the ships even had their water-tight doors sealed and by 7:55 AM, all were underwater.

As Dutch and English vessels rescued what survivors they could and Royal Navy destroyers searched the Sea for the hateful foe, Weddigen, gliding U-9 unseen beneath the waves, headed home. He was welcomed as a hero. Not only had he been married the day before he left for this mission, but he had also suddenly become the most successful submarine captain in the seas. The Kaiser awarded him the Iron Cross First Class, his entire crew the Iron Cross Second Class.

With her keel uppermost she floated until the air got out from under her and then she sank with a loud sound, as if from a creature in pain.

-From A Memoir of the Sinking of the Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue by U-boat U-9 in September 1914 by Lieutenant Otto Weddigen

In Britain, the story was quite the opposite. Horror and outrage at the loss of 1,397 sailors and 62 officers gripped the nation. Captains and Admirals were reprimanded. According to Weddigen’s memoir of the event, British news reports stated that the cruisers had been sunk by a flotilla of six German U-boats flying Dutch colors.

Of the 777 sailors and 60 officers that survived, one was Kit Wykeham-Musgrave, who was 15 at the time and stationed on the Aboukir. When his ship went down, he managed, swimming against the suction, to escape and was pulled aboard the Hogue, just before it was struck. As this ship went down, Musgrave again slipped out of death’s fingers to board the Cressy. When this, too, went down, he clung to life on a piece of driftwood, unconscious, until being rescued by a Dutch trawler.

From that day forward, Britain and Germany understood the great threat and devastating impact of submarines. The U-9 alone would sink 18 ships by the time she was pulled from the front line in 1916.