Trench warfare is the iconic image of the First World War. All along the Western Front, the battle ground to a halt as the opposing armies dug in. Siege-works ran across half the width of Europe.

How did the entrenchment occur and what were the different approaches of the forces involved? Not everyone dealt with the situation in the same way.

War Becomes Entrenched

Ironically, the trenches began as a way for both sides to continue a mobile form of warfare.

At the start of World War One, the military leaders of the combatant countries expected a fast-moving conflict. Their tactics involved using devastating modern weapons to create breakthroughs which they could exploit using fast-moving troops.

These destructive weapons had the opposite effect. Artillery and machine guns made attacking a position incredibly difficult. Troops out in the open were more vulnerable than ever before. Attacks were tougher than ever.

The war on the Western Front became a series of failed flanking maneuvers. This so-called “Race to the Sea” involved each side trying to get around the other’s flank and control ports with access to the English Channel and the North Sea.

As these advances stalled over and over again along the line, men dug in. Tactically, the purpose of the trenches was evident. They provided soldiers with safe positions to defend, making it easier to hold ground.

Operationally, they served a more offensive purpose. Trenches allowed an area to be held by fewer men than were otherwise needed. This freed troops for the big assaults that were meant at first to out-flank the enemy and later to pierce their defensive lines.

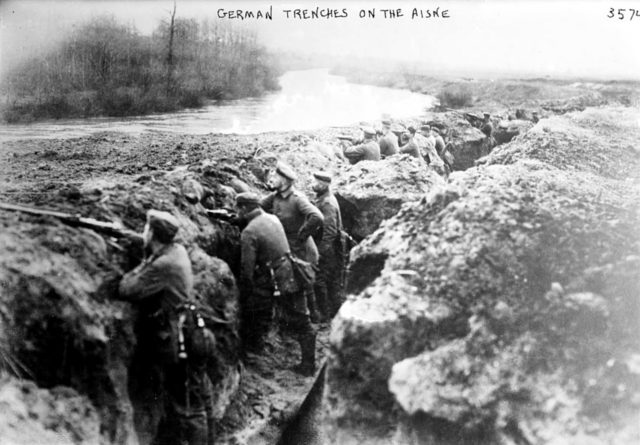

The Germans

On the Western Front, the German forces were the most defensively focused. Although they had been the ones to make advances at the start of the war, other areas of combat forced them to concentrate on holding what they had.

Fighting a war on two fronts, the Germans could not pour all their men into the Western Front. Instead, they put as much effort as possible into the more fluid Eastern Front, hoping to knock Russia out of the war. Once completed, they could turn their attention west.

The Germans on the Western Front, therefore, knew they were there for the long haul. The shorter length of the front meant it could be held with fewer men than in the east. Their job was to hang on.

General Erich von Falkenhayn ordered the Germans to build strong entrenchments along the whole front line. Shell-proof shelters provided somewhere for the troops to take cover during artillery bombardments. Where the soil permitted it, as in the Somme’s chalk hills, there were deep dugouts. These could become relatively comfortable barracks, with electric lights and floorboards.

As time passed, the Germans deepened their layers of defense, building a second and then a third line, in case the first was overrun. Far back from the fighting, it was easier to create strong defenses in these lines, including pillboxes and dugouts. The Hindenburg Line, which they fell back to in the spring of 1917, was particularly well fortified.

Offenses by the British became part of the German defensive strategy. If the line was breached, they made swift counter-attacks to block the hole and maintain the integrity of the defensive system. This was achieved by securing the flanks of the broken area to prevent the line further unraveling, then moving troops into the gap.

The British

The British philosophy was the polar opposite of the Germans. Commanders such as Sir Douglas Haig remained intent on an aggressive campaign throughout the war. They saw the trenches as an interim step.

The British trenches were not therefore designed to provide a long-lasting defensive system. Instead, they were a temporary measure used to bring large volumes of troops forward safely. Theirs was a rabbit warren through which fighting men could be funneled to the attack.

Their use of the trenches was also the most aggressive, until the German advances in the late stages of the war. Trench raids were used to maintain pressure on the enemy. The trenches were consistently gaining new complicated extensions. Big pushes were made to try to break the German line.

Similarly, the experience of British pilots was shaped by this difference in approach. They were usually the ones on the offensive, flying over German lines. This gave the edge to German pilots such as the Red Baron as they did not have to fly as far to fight. Conservation of fuel let them stay in the action longer. If they were shot down, they would probably land behind their own lines, while the British were likely to be captured.

Despite their intentions, the result was much the same for the British as it was for the Germans. The tools and techniques available were similar – barbed wire, minefields, and long ditches dug out of the earth. To ordinary soldiers, the results also looked the same.

The French

In principle, the French government and generals took an aggressive approach to the Western Front. They had lost land to the German advances. This stung their patriotic pride and shook national morale. It also harmed their ability to fight by depriving them of natural resources. They pushed hard for attacks early in the war, but once it became entrenched, the French shifted to a more pragmatic stance.

Some areas of the line were more static than others. Despite fierce fighting in the first winter, the Argonne forests and Vosges Mountains saw little movement. There seemed no benefit in fighting there, and so these became defensive areas. Up and down the lines, the French defined sectors as either active or passive. This way, they could dig in properly in the passive areas, much as the Germans had. Meanwhile, they stayed on the offensive in the active areas, much like the British.

For them too, the result was a familiar one. A long, drawn-out, and mostly immobile war in the churned up mud. A difference in philosophy did nothing to break through the stalemate technology had created.

Sources:

Martin Marix Evans (2002), Over the Top: Great Battles of the First World War.

Richard Holmes, ed. (2001), The Oxford Companion to Military History.