The First World War was defined by trench warfare. While trenches had played a part in previous conflicts, never before had they been so crucial. For four long years, the two sides faced each other in a two-way siege the length of the Western Front.

These trenches were more than crude holes in the ground. By the end of the war, many had become sophisticated feats of military engineering.

The Emergence of Trench Warfare

Trench warfare emerged by accident on the Western Front.

At the start of the fighting, both sides expected a war of movement. But their attempts to outmaneuver each other failed, forcing troops to hold their ground.

Soldiers started digging in, creating improvised defensive positions that most expected to be temporary. As maneuvers ground to a halt, men found themselves in one place for a long time, under fire from an ever-present enemy. They started digging deeper, more solid trenches.

Trench Layouts

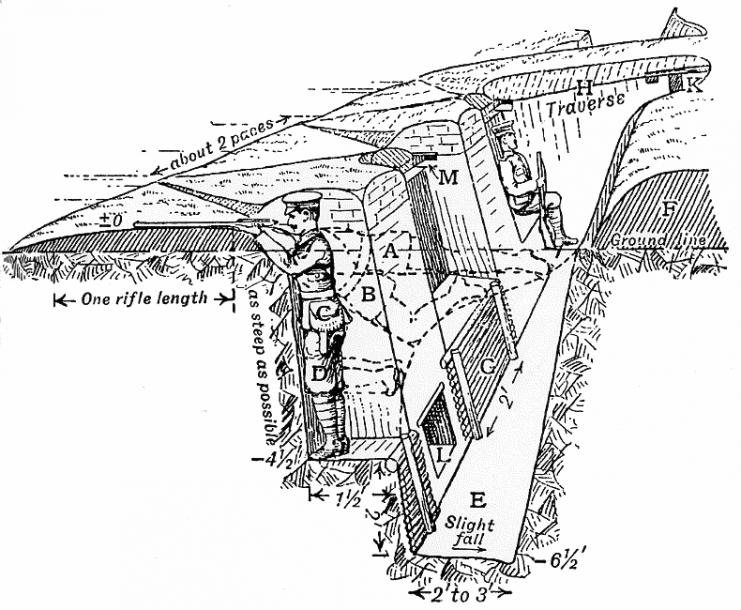

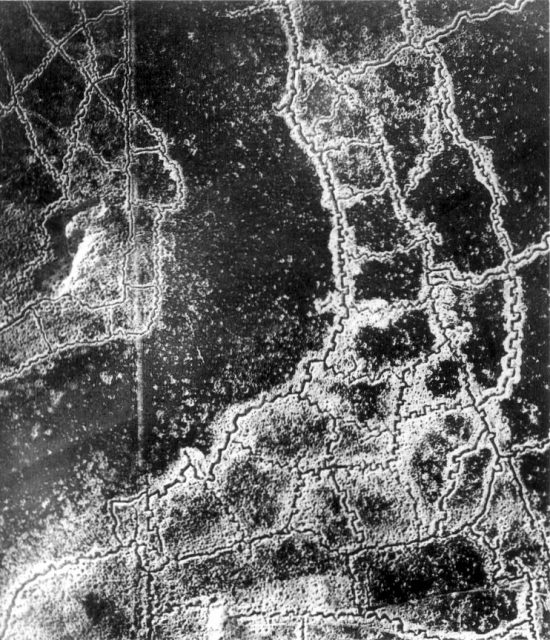

A typical defensive system was made up of three lines of trenches about 800 yards apart. These ran parallel with the front line, providing protection from fire from the opposite trenches and letting men hold their ground.

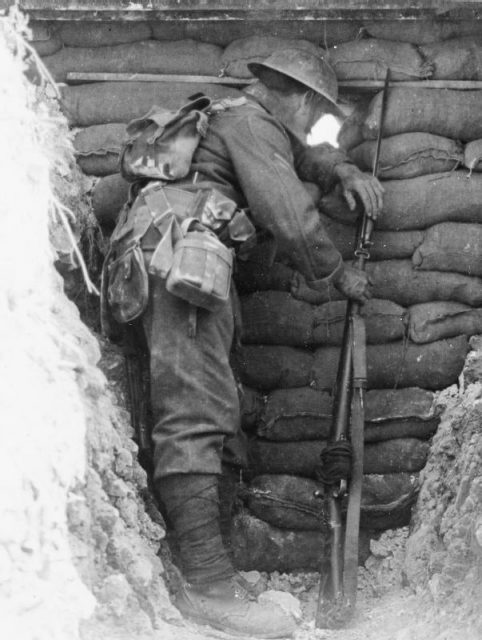

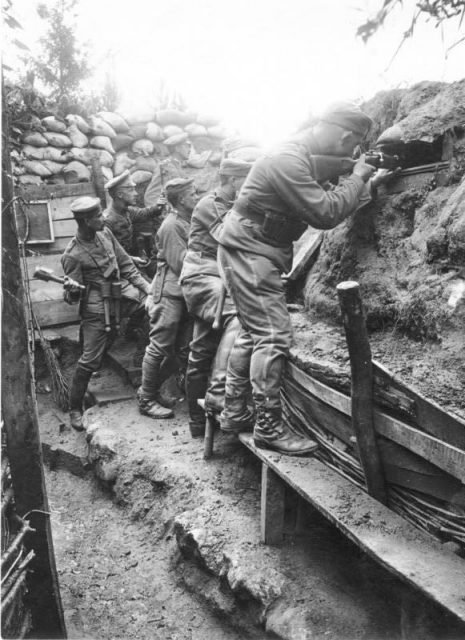

The line nearest the enemy was the fire trench. This was where soldiers regularly saw combat, whether the low-intensity warfare of sniping and pot shots or the higher intensity work of fighting off raids and frontal assaults. Behind this came the support trench, offering supporting fire to the front line, and then the reserve trench, holding more men ready to be flung in against a direct assault.

These trenches were not straight lines. Instead, they zigzagged or had protruding firebays. These irregular layouts meant that if a shell hit then its blast and shrapnel wouldn’t travel a long way down the trench. This reduced the number of casualties.

The main trenches were connected by communication trenches running off them at right angles. These connected the trenches to each other and to other forces to their rear. The communication trenches were more likely to be straight lines, as men weren’t sheltering in them from attacks, and runners might need to get along them quickly.

Both sorts of trenches were shored up with wood to stop the sides collapsing. Sandbags added extra protection and duckboards on the ground helped with drainage.

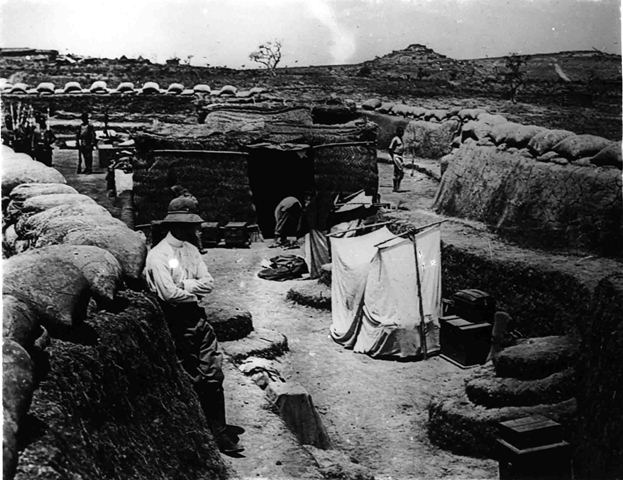

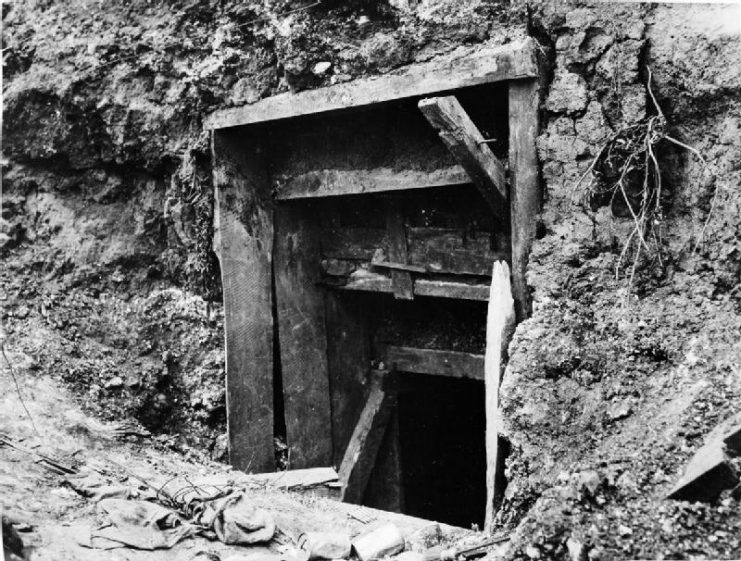

Dugouts were created in the sides of the trenches or deeper underground. The Germans became particularly sophisticated in creating these, producing deep, concrete-lined rooms. These gave men more shelter in which to live their everyday lives.

More importantly, they offered greater protection from artillery bombardments. The trenches themselves had shelters and overhead covers in some places, but these offered protection against the weather, not falling shells.

Latrines, kitchens, and dressing stations all had their places in the trench systems. Kitchen and medical stations might be shelters toward the rear of the rows of trenches. Latrines needed to be available near the very front. They were often built in smaller trenches running off the others, to isolate the stinking and unhygienic space.

Maintaining the trenches involved a lot of work. The dugouts in particular had to be constantly shored up and re-dug.

Local Variations

The design of trenches varied with the local terrain.

In some areas, trenches were built above the ground rather than dug out of it. This happened for two reasons. One was that the bedrock might be near the surface, making digging too difficult because of its solidity. The other was that the water table might be near the surface, as happened in Belgium, at the northern end of the Western Front. Here, sunken trenches quickly flooded, making them useless as shelters.

In other areas, the mountainous terrain got in the way. This made it harder to dig trench lines, but also less necessary, as the terrain itself contributed to defenses. This happened on the Italian Front, where mountain-top strong-points offered the combatants mutual defense across craggy valleys. Trenches formed part of the defenses but not complete lines running across the landscape.

Defense in Depth

From 1916 onwards, the Germans adopted a more sophisticated approach to their trenches, based around defense in depth.

The trench line facing the enemy was no longer designed to hold out against a full Allied assault. Instead, it consisted of relatively modest strongpoints built around concrete pillboxes and large shell-holes, connected by trenches. This was designed not to stop a focused attack but to delay it and channel the attackers into exposed kill zones.

Up to a mile behind this was the main front line. This was a tougher network of interconnected strongpoints, all supporting each other. Again, the German command accepted that this line might fall. As a result, the strongpoints were designed to be tough at the front but vulnerable to the rear, in case the Germans had to retake them in a counter-attack.

Behind the front line was the battle zone, an area of numerous strongpoints and short trenches. Over a mile wide, it was designed to hold up the enemy and provide really tough fighting terrain, giving the Germans time and space in which to launch a counter-attack against an increasingly exhausted enemy.

Finally, there was the reserve zone, containing the artillery, troop reserves, and more defensive trenches.

Saps

Narrow, temporary trenches called saps were used to launch attacks against the main defensive trenches. Dug out into no man’s land and then joined together in new trench lines, these offered troops a way to get close to the enemy before they attacked, as well as safe, concealed positions from which to listen in on the enemy. They were a laborious way of progressing an advance, but of potentially huge benefit to attackers.

The trench lines were a formidable defensive network. They were one of the reasons why the war remained so static until early 1918. It is why they are now remembered as a defining feature of the war.