The Western Front of the First World War was effectively a massive siege. Both sides sat behind lines of defences, hurling artillery shells and making attempts to seize heavily fortified enemy positions. One of the techniques they used, and one that had been popular for centuries, was mining.

The Tunnels Begin

From the 5th to the 12th of September, 1914, the Allies brought the German offensive to a halt at the First Battle of the Marne. With the war of movement over, both sides settled in, digging trenches and building defensive positions from which to face each other.

Within weeks, the French and German forces had adopted one of the classic tactics of siege warfare – undermining. Traditionally used against castles, undermining involved digging beneath enemy walls, then either detonating an explosion or setting fire to the tunnel supports, so that the ground would fall in and the defences break.

The French began mining in October, including counter-mines to prevent the Germans approaching their positions. On the 11th of November, the Germans captured some French engineers and learned about this extensive mining activity. They too began to dig in earnest.

The first great success with mines came on the 20th of December, when German mines blew holes in British positions, shaking the defenders both physically and psychologically, and allowing German infantry to launch an overwhelming attack.

The British initially suffered from a shortage of engineers. In late 1914 and early 1915, they joined in the underground operations, but at a disadvantage.

Counter-Mines

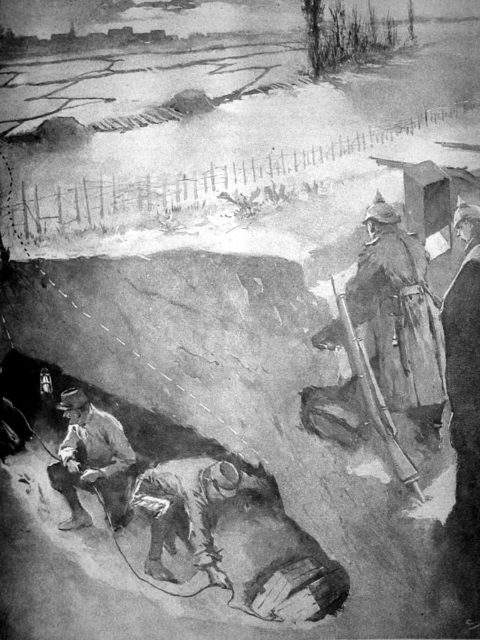

Counter-mines were a vital part of underground warfare. These were mines designed to reach, detect and disrupt enemy mining operations. When they met the other tunnels, vicious hand to hand fighting sometimes took place under the ground. On other occasions, explosives were detonated in one mine to disrupt another.

January 1915 saw intense counter-mining operations between the French and Germans around Massiges. Both sides sought to interrupt each other’s tunnels by detonating explosives near them. Part of the skill of this warfare was in listening for sounds that would show enemy positions. The Germans bluffed by intensifying their efforts in defensive tunnels, trying to distract from the attack tunnels.

The Technology of Military Mining

As the war progressed, all sides recruited experienced civilian engineers and miners into their mining units. The British brought in men from all over their empire, channelling the expertise of diggers from Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Civilian experts brought with them new technology and ideas.

Much of this was about the fundamentals of building a durable tunnel. Australian miners used greased hemp to seal the joints of mine shafts, preventing water from seeping into the tunnels, an important step in ground soaked by winter rains. Spiling allowed tunnels to be dug in the damp, unstable sands along the Belgian coast.

A range of ingenious tunneling devices was built. The French deployed such machines as the Guillat-Génie hand borer, used for creating ventilation holes, the Ingersoll screw drill, and explosively powered forcing jacks.

The British Stanley Heading Machine was adapted from its regular using cutting coal to dig five-foot-high tunnels through clay soil. One remains below the ground of the Van Damme Farm, 100 years after it went into use.

Gadgets played an important part in detecting enemy tunnels. The geophone worked like a doctor’s stethoscope but placed on the ground for a soldier to listen for movement. Water bottles were turned into improvised listening devices. Later in the war, the French invented the seismomicrophone, a box containing a lead mass held in rubber rings which transmitted data to a receiver.

Mining and Infantry Attacks

As well as being used to destroy enemy defences, mines could be used to get infantry close ready for a surprise assault. The main tool for achieving this was the Russian Sap, a tunnel dug close to the surface straight towards the enemy lines. It lacked timber support and had only a foot of dirt above it so that infantry could burst through the roof and pour out into enemy positions.

A French development, the Russian Sap was used extensively by them in 1915. In September that year, the French tried to launch a mass assault from such tunnels at Artois, while the British did the same at Loos. In both cases, the saps contributed little to the battle. They suffered from several drawbacks, including the fact that friendly artillery bombardments risked hitting them as they came close to the enemy.

The Hawthorn Mine

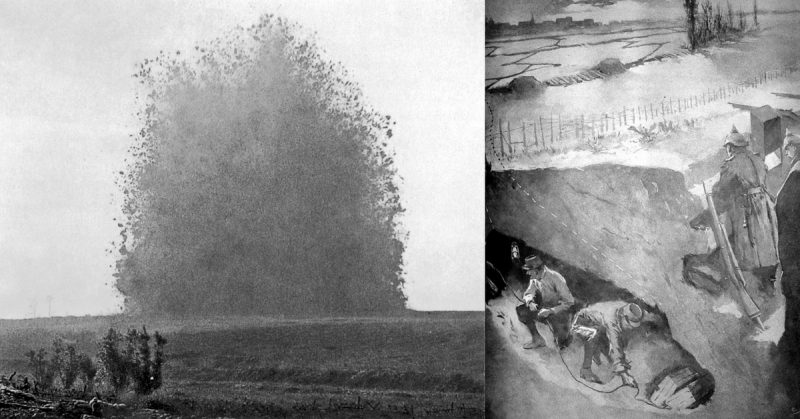

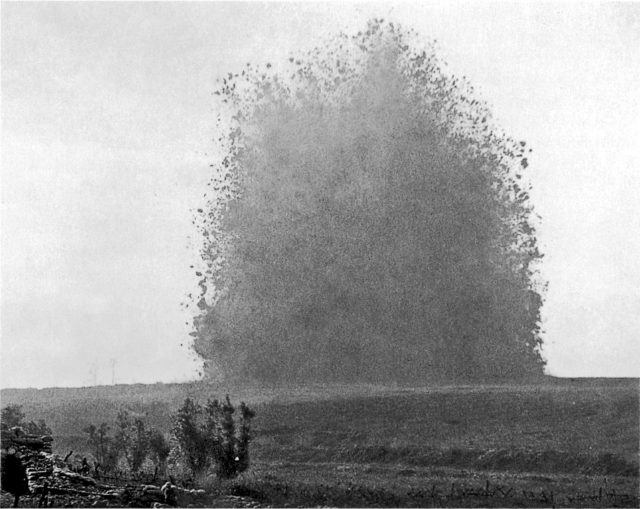

One of the most famous mines of the war was used by the British at the start of the Battle of the Somme. At 7:20am on the 1st of July, 1916, 18 tons of high explosives were detonated beneath the German strongpoint called Hawthorn Redoubt. The hill it was on was almost flattened and all the Germans in the redoubt were killed. The moment of the explosion was captured on film by a British cameraman.

But the Hawthorn explosion, like much of the preparation for the Somme offensive, was not as effective as General Haig hoped. German troops remained in place along the adjacent lines and devastated the advancing British with machine guns. It didn’t help that the British had over-estimated how long it would take debris to fall from the air, and so left too much time for the Germans to recover before starting their advance.

Messines

By June 1917, other forms of attack were taking the place of mining. The Battle of Messines, fought from the 7th to the 14th of June, therefore saw the last as well as the greatest mining assault of the war.

This time, the British got it right. Placing explosives directly beneath German positions all along the line, they shattered the enemy’s defenses. Mines allowed them to gain an edge in the initial attack, pushing back the Germans.

But the days of the military mine were over, for that war at least. It had been hard, dirty work, and few of those involved would be sorry to leave it behind.