War History Online Presents this Guest Blog From Christopher Sandford – author of the book “Zeebrugge 1918: The Greatest Raid of All”

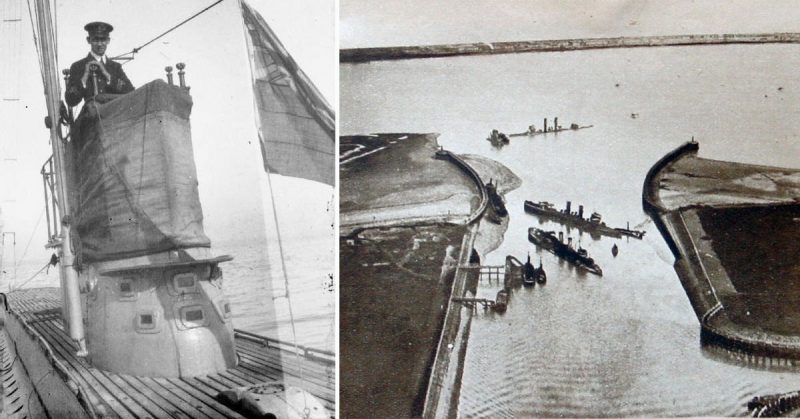

Shortly after midnight on Tuesday 23 April 1918 – St. George’s Day – a 26-year-old Royal Navy lieutenant and bishop’s son named Richard Douglas Sandford lined up his submarine C3 for a head-on collision with the viaduct of Zeebrugge harbor. His mission was to destroy the narrow causeway linking the harbor’s ‘mole’, or seawall, to Zeebrugge itself, and thus prevent the occupying German forces from reinforcing the area.

Meanwhile, about a mile away to the north the cruiser HMS Vindictive landed a party of sailors and marines whose brief was to storm the mole and spike the enemy’s guns, while three further British ships, each loaded with about 200 tons of concrete, slipped into the harbour and, amidst the confusion, scuttled themselves in a way that prevented the Germans from using the area as a forward base for their U-boat operations in the North Sea. The whole interlocking machinery of the Zeebrugge Raid went under the codename ‘Operation ZO’, and when the dust finally settled Winston Churchill came to reflect, ‘It may well rank as the finest feat of arms in the Great War, and certainly as an episode unsurpassed in the history of the Royal Navy.’

As it happened, Richard Sandford had something to prove that night beyond merely his ability to steer a 300-ton submarine, packed with amatol explosive, into a heavily defended enemy harbor, blow it up, and then escape as best he could in a small dinghy. There was a personal motivation as well. Just ten weeks earlier, Sandford had been one of the officers involved in a large-scale British fleet exercise off the coast of Scotland that came to be known as the Battle of May Island. Several ships had managed to collide with one another in the dark, and a total of 104 men perished as a result. Sandford had been the officer of the watch on the submarine K6 when she struck her sister ship K4. None of K4’s 59 crew survived her sinking.

An official note of censure read: ‘Sandford [was] informed by Admiral Beatty that blame attributable to him for not at once appreciating the necessity of getting clear, and not taking action to do so.’ This was a serious enough rebuke for any ambitious young officer, quite apart from the moral responsibility he might have felt for the deaths of his fellow British servicemen.

So when the opportunity for redemption presented itself, Sandford was ready. C3 struck the Zeebrugge viaduct exactly as planned, her bows lifted by the force of the collision into the mesh of steel girders and stanchions above, and exploded with a force that temporarily silenced even the raid’s other individual skirmishes. Standing nearly a mile away, a sailor named Harry Adams remembered: ‘There [was] a deafening explosion, a thud that shook Heaven and Earth – the nearest approach to an earthquake one could imagine. We had been warned to expect it, but amongst everything, it had passed from one’s mind … The convulsion threw you to the deck.’

Incredibly, Sandford (though shot twice) and his five shipmates on board C3 all survived and eventually made their way safely back to England. Theirs was the one part of the whole intricate apparatus of Operation ZO to go entirely, and spectacularly, to plan. Two of the three Royal Navy blockships managed to sink themselves at least close to their target, although the Germans were soon able to dredge a channel for their U-boats to pass by them. The third British ship went aground and had to be abandoned roughly half a mile out of position. There were some 600 casualties, including 225 deaths, out of a total complement of 1,600 who took part in the raid.

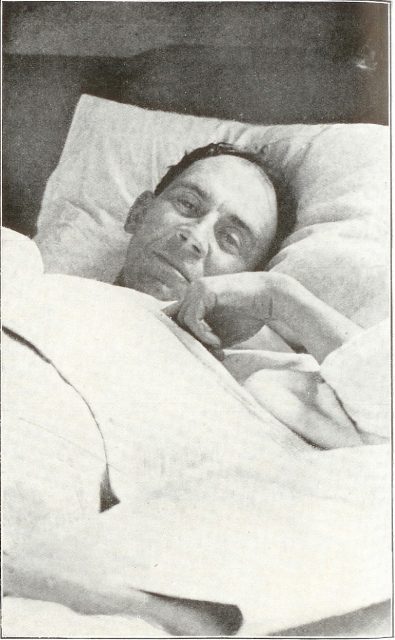

Sandford recovered from his wounds, and was one of the eight heroes of Zeebrugge to be awarded the VC at a ceremony held at Buckingham Palace on 31 July 1918. Some weeks later he fell ill and was taken to Eston Hospital in North Yorkshire. Richard Sandford died there on 23 November, of what was probably typhoid fever, just twelve days after the armistice that ended the war. He was 27. Towards the end Sandford was able to read a note from Admiral Beatty, commander-in-chief of the Grand Fleet, warmly congratulating him on his award. He had surely atoned for his mistakes.

Christopher Sandford’s book Zeebrugge 1918: The Greatest Raid of All (Casemate) is available now: Casemate US and Casemate UK.