The early days of the First World War were very different from the long years that followed. As German troops advanced into Belgium and France, there was a brief war of movement. In a series of engagements, soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) gave ground before the onrushing invaders, while trying to find ways to outflank them.

There were several short, sharp engagements in which the weapons of the First World War – particularly artillery and machine guns – came extensively into play. The war’s defining tactics of entrenchment and heavy bombardment were not yet present.

One such battle took place at Le Cateau.

Covering the Retreat

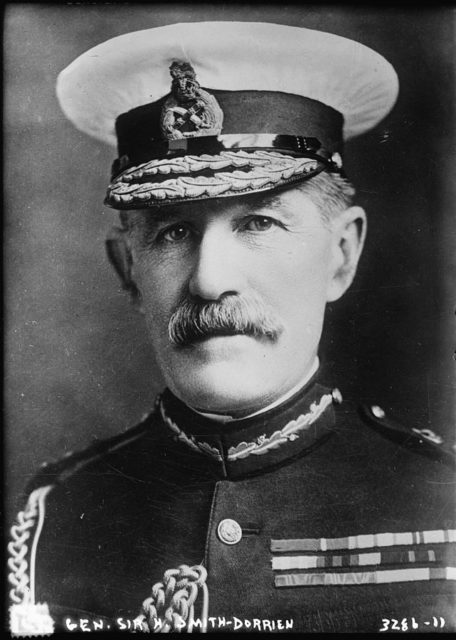

On August 26, 1914, General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien had a problem. As one of the commanders in the BEF, he had orders, but he could not fulfill them.

Smith-Dorrien’s troops, like many in the BEF, had been through a grueling two weeks. They had marched from France to Belgium, fought, and then marched away again. Now they had been caught by surprise, as German forces came through a forested region the Allies had considered impassable to armies.

Field Marshal Sir John French was pulling troops back amid a cloud of confusion. His order to Smith-Dorrien was to join in this retreat.

Smith-Dorrien however, could see what the Field Marshall could not. A withdrawal now would be disastrous. The Germans already occupied a hill the Field Marshall had expected to be used in covering the retreat. A straight-forward retreat would risk Smith-Dorrien’s men being enveloped by the German First Army.

Under the circumstances, Smith-Dorrien saw only one option. He ordered his men to take up positions on the ridge south of Le Cateau and fight the Germans there.

Open Ground

Fighting began early in the morning, as German soldiers entered Le Cateau. There they encountered British troops who had not yet been able to reach positions on the hill; the 1st Devon and Cornwall Light Infantry and the 1st East Surreys. There was a skirmish, after which the British soldiers pulled back to the hill line.

There they found themselves even more exposed than they had been in the town. This was a region of softly rolling hills and large open fields which would usually be growing grain. There was barely a terrain feature to take shelter behind.

Using what little scenery was available, the troops prepared a defensive line. Hurriedly, they dug shallow trenches to protect themselves from enemy fire.

German artillery was approaching close behind the advancing infantry; so close the infantry reserves were behind these field guns. As the men of Cornwall, Devon, and Surrey dug in, artillery began to pound the hillside.

A Napoleonic Defense

The fiercest fighting took place on the British right. There the German 5th Division found the flank of the British 5th Division and set about trying to roll up the defenders’ line.

Artillery shells rained down on both sides of the battlefield. British gunners caused enough carnage to slow down the German infantry. The Germans succeeded in hitting not just the British batteries but the infantry defending them. The 2nd King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry and the 2nd Suffolk Regiment took heavy casualties. An attempt was made to reinforce them with the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and the 2nd Manchesters, but these troops were unable to get through.

The Germans pressed their advantage on the right. The British were forced back, the artillery forming a line at right angles to their original position while continuing to fire at the advancing Germans. An officer later compared it with the soldiers of Wellington’s era and the open squares they had formed against the French.

Withdrawal

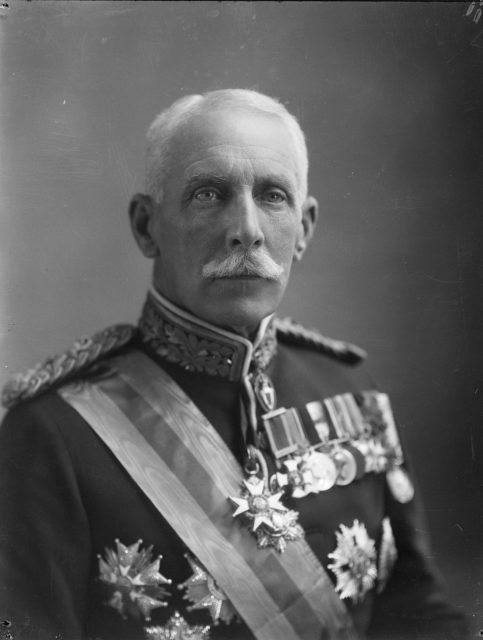

By midday, it was evident the line along the hill could not be held. The British were under pressure everywhere. Their right flank was being pushed back. Soon, the Germans would be wrapping around British units. The commander of the 5th Division, Major General Sir Charles Fergusson, told Smith-Dorrien his men would have to give up their position.

Smith-Dorrien sent out orders for an orderly withdrawal. He wanted to extricate his men from the chaos on the hill without allowing the whole line to collapse. This order reached Fergusson at 1400, and within the next hour, it reached most of the forward units.

The British fought fiercely to get their valuable artillery out as they retreated. Three men of the 37 (Howitzer) Battery won Victoria Crosses for their heroic actions during the withdrawal – Captain Douglas Reynolds, and drivers Fred Luke and Job Drain.

On the left, French forces saved the British from heavy losses. The Cavalry Corps of General Sordet, along with French Territorial reservists, held the Germans near Cambrai, giving the British time to retreat.

The Scattered Remains

Sadly, some units on the British right never received the order to retreat. Amid the deadly chaos of battle, the men bearing the orders did not get through, and soldiers were left behind.

The King’s Own Yorkshires and the Suffolks, caught at the fiercest part of the fighting, fought to the end.

Other groups were left isolated as the army withdrew and German units moved on past them. They headed west and south, hoping to meet up with the rest of the British forces. Some fought against the Germans who had bypassed them. Others made their way to the Channel coast. Many were eventually reunited with their units, ready to continue the war. Two men hid in the village of Bertry and while one of them was eventually shot by the Germans, the other survived.

The British lost 7,812 men at Le Cateau, dead, wounded, or captured. It was a high price to pay, but Smith-Dorrien was finally able to follow his orders and withdraw.

Source:

Martin Marix Evans (2002), Over the Top: Great Battles of the First World War.