By February 1916, the German advance into France had long since ground to halt, there was little movement on long front line and the conflict had become a war of attrition. For much of World War I in the West, the rival armies were locked into prolonged battles at a few key places like the Somme or Verdun. And it was at Verdun that German General and Chief of Staff Erich von Falkenhayn planned to draw the French into a bloody battle that would bleed them of enough men and material, to cause their morale to collapse, and this would lead to their surrender.

10. Verdun was not just a fortress, but the center of a large array of powerful fortification

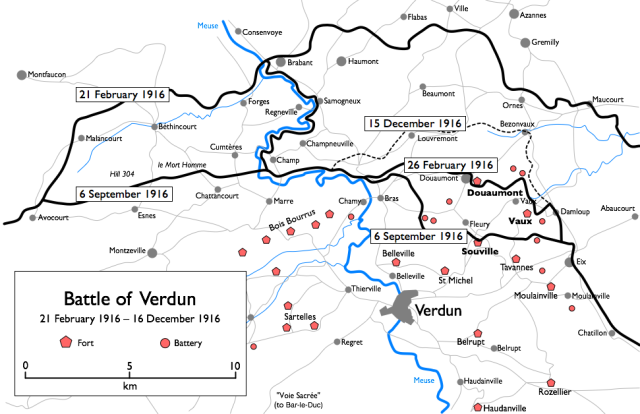

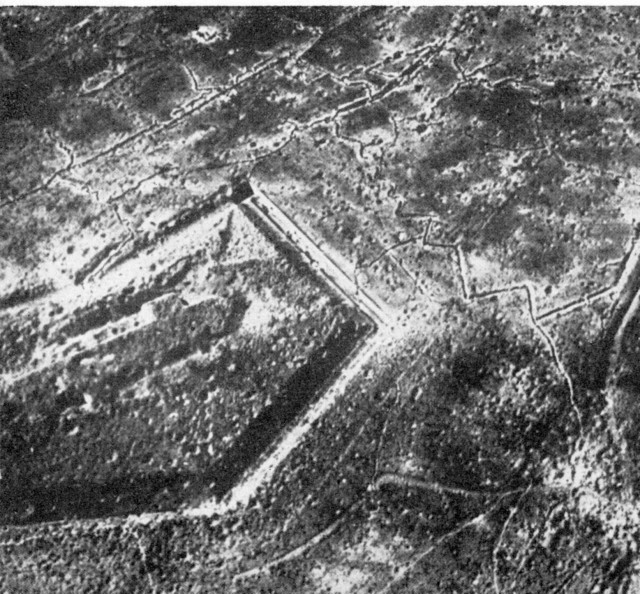

Verdun has long been key to France. It has a place in military history that stretches back to the thwarting of an assault by Attila the Hun in the area in the 5th century. Since the 1870’s, the French had been turning Verdun and the surrounding area into a fortress, creating a double ring of 28 fortresses and ouvrages (often artillery batteries), all at least 150 meters above the valley and Meuse river. These were positioned with good views of each other to provide visual and operational support.

The construction of these defenses included steel-reinforced concrete several meters thick, networks of protected bunkers, concrete trenches, and shell-proof turrets. Around 1,000 pieces of 150mm and 75mm artillery were stationed throughout these complexes as well as strategically placed machine guns.

Verdun was a fortress and would not to be taken lightly.

9. Falkenhayn hoped attrition of French forces would lead to a German victory in the War

Falkenhayn believed he could take the system of fortresses and Verdun itself, causing the French to commit entirely to retaking it. This would drain the French of manpower and, in turn cause the British to mount a relief offensive and expend their troops as well. His plan was then to force the French to negotiate for peace or just mop up what was left of the Entente’s armies along his Western Front.

Though the German 5th Army managed to capture several fortresses and key points over the months and months of slow, costly battle at Verdun, they never succeeded in capturing their main targets and certainly not Verdun itself.

8. Though Falkenhayn couldn’t take Verdun, he still believed he could cause enough casualties among the French forces by using massive amounts of artillery

The Germans began their assault at Verdun with well over 1,000 artillery guns, many of which were behemoths. The largest guns they used at Verdun were 450mm and could fire several kilometers. From the onset of Verdun, Falkenhayn believed he could basically blow the French army to pieces.

Before the first German assault on February 21st, 1916, they launched a 10-hour bombardment with 808 guns. Over 1,000,000 shells were fired and the rumbling of the explosions could be heard 160 kilometers away.

7. The French learned the values of using artillery en mass and they sure used it

Though originally believing that a war of material would be too slow and, in the end, cause more casualties, the French needed an answer to German artillery. By June, the French had over 2,700 artillery pieces at Verdun, focusing heavily on their 75mm guns. By the time the French had retaken every fort around the city and effectively won the battle in December 1916, the two sides had fired around 10,000,000 shells at each other.

6. What Falkenhayn didn’t anticipate was French resilience

After the first few months of battle, the Germans believed they were out-killing the French 5:1. Historical analysis of casualties, however, range from 1:1 to 3:1 and German intelligence was very far off.

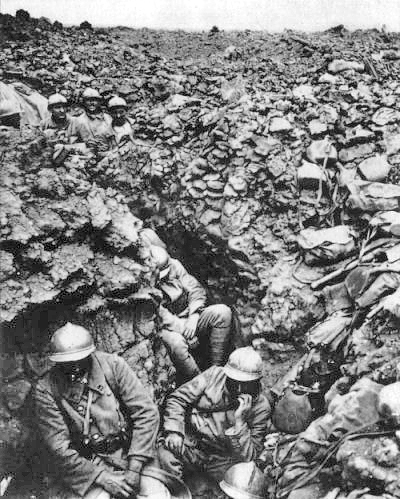

The French commander, Philippe Pétain, also adopted a rotation system that kept French battalions in the trenches for far shorter stretches of time then their German counterparts. Throughout the course of the battle, 85 French divisions saw action at Verdun compared to 48 German divisions.

Verdun had become very symbolic to the French and they weren’t about to let it be taken by the Germans. Falkenhayn’s attrition strategy seemed to be failing and by the end of April, most of his strategic reserve was committed to Verdun.

5. The back and forth of the two armies went on for months

The battle of Verdun lasted from February 21st to December 20th. German and French forces pushed each other in and out of several fortresses, ouvrages, and towns. One village, Fleury, was captured and recaptured 16 times throughout the year.

4. Soldiers on both sides of this battle called it Hell

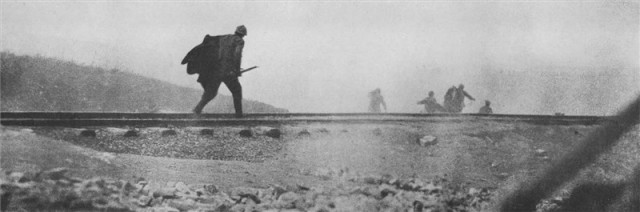

The millions of artillery shells that pummeled the land around Verdun demolished buildings and leveled forests. The rains turned the pulverized earth to mush and the shell craters into murky, slippery pits men drowned in. The battlefield was a wasteland filled with mud and dead soldiers.

Many tried to desert, many more became shell-shocked. This was the madness and terror of the Great War that poems and stories by the men who fought there try so desperately to convey, maybe to prevent from such a war from ever happening again. Massacre and carnage defined life in this hellscape.

3. The final French assault to retake the fortifications around Verdun came on December 16th

After six days of blasting 1,169,000 shells at the German positions, four French divisions advanced preceded by two lines of continued bombardment from their artillery. Of the 21,000 German troops in the assaulted front positions, 13,500 were lost. The French took over 11,000 prisoners caught while still undercover from the artillery barrage.

The German line had collapsed. The French now controlled every strategic position around Verdun.

2. The toll of the battle was immense for both sides

Estimates of casualties range from 315,000 to 542,000 for the French and 281,000 to 434,000 for the Germans. Several credible sources have placed casualty figures for both sides in the mid-300,000 range.

1. The legacy of Verdun has become one with a message of peace

Verdun is both a symbol of French pride and one of Franco-German reconciliation. Since the 1960’s, both nations have made symbolic efforts focusing on Verdun to mend the pain two world wars caused each other. The capstone of this bonding could be the image of German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and French President François Mitterrand holding hands in heavy rain at Douaumont Cemetery in 1984.

By Colin Fraser for War History Online