A quick look at the fall of France in May 1940.

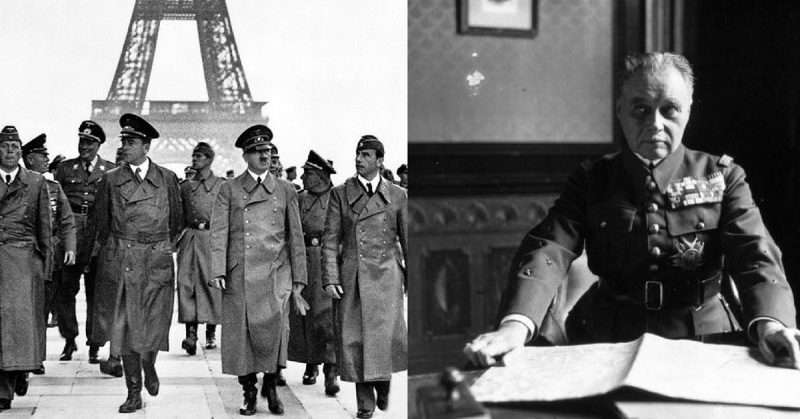

1. The French Were Led by Maurice Gamelin

At the start of the Second World War, the French general staff were led by General Maurice Gamelin, an officer widely respected by both allies and opponents. A veteran of the First World War, he was credited with much of the planning that led to victory at Marne in 1914. Since then, he had tried to modernize and mechanize the army.

But Gamelin was suffering from neurosyphilis, whose symptoms include lapses in concentration, memory, judgment, and intellect. Gamelin’s own memoirs showed paranoia and delusions of grandeur. His strategy was grounded in First World War tactics, despite changes since then. As the French were driven back by Germany, he sacked twenty front line commanders, scapegoats for his failure, rather than accept that his plans had been flawed.

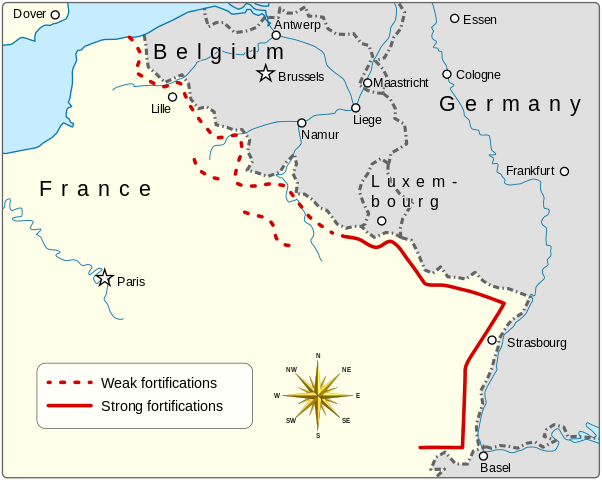

2. Their Main Defense was the Maginot Line

Gamelin’s defense of France relied upon the Maginot Line, a line of concrete fortifications running the length of France’s border with Germany. This was meant to make it difficult the Germans to invade France directly, giving the French time to prepare.

To avoid offending the Belgians, the line did not run past their border all the way to the English Channel. As a result, despite its near-impregnable concrete defenses, the Line became useless, with the Germans simply advancing around its northern edge.

3. Gamelin Relied on a Slow Defensive Strategy

![Hitler watching German soldiers marching into Poland in September 1939. Photo Credit. UBz: eine der packendsten Szenen; deutsche Soldaten, die während ihres Vormarsches am Führer vorüberziehen. 4.2.1940 [Herausgabedatum]](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2016/09/bundesarchiv_bild_183-s55480_polen_parade_vor_adolf_hitler-640x426.jpg)

Very little effort was made to invade Germany or weaken her infrastructure with targeted bombing. The initiative, and so the course of the war, was left in German hands, and the Germans were given time to finish fighting in Poland and then after their victory in the east to move troops west.

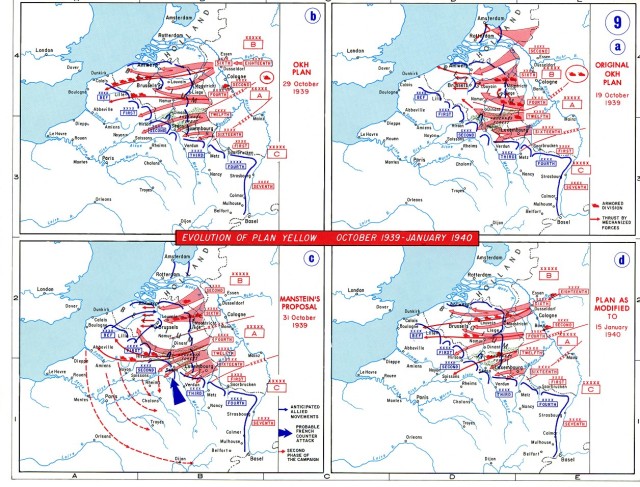

4. Germany Succeeded Using the Manstein Plan

German success was founded on a plan developed by General Erich von Manstein. Rather than advance primarily across the open plains of the Low Countries, the Germans focused two-thirds of their forces, including three-quarters of the available tanks, in a single strike along a narrow front through the Ardennes Forest. This area was weakly defended, as the French believed it was impassable to tanks.

The Germans proved them wrong.

5. They Divided the Allies with the Sickle Stroke

Having smashed their way into France, German forces then followed a move known as the Sichelschitt (sickle stroke). Sweeping south across France at remarkable speed, they divided the Allied forces into two parts, separated by the “Panzer corridor” of German armor.

Communication lines between the halves were cut, and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was left isolated in Belgium.

6. 340,000 Allied Troops Escaped Through Dunkirk

With German victory imminent, the British decided to save what forces they could. Only one Channel port was still in their hands, and so the BEF withdrew to there. This port was Dunkirk.

Despite German bombing of the harbor, the British conducted a successful seaborne withdrawal in the form of Operation Dynamo. Over the course of 8 days, 848 ships rescued 340,000 fighting men, two-thirds of them British. It was an extraordinary achievement, but one with substantial losses – six destroyers were lost, 19 damaged, and the soldiers’ equipment had to be left behind.

7. Italy Joined on 20 June

At the start of the Second World War, Italy avoided committing to the fighting, despite Mussolini’s political closeness with Hitler. Some in Britain even hoped that Italy might be persuaded to join their side, as in the First World War. On 22 May 1940, Mussolini signed a military alliance with Nazi Germany – the Pact of Steel. On 10 June he declared war on Britain and Germany, and on 20 June invaded southern France. By then the Battle of France was almost over. The Italian troops made only limited progress and made almost no strategic difference.

On 10 June he declared war on Britain and France, and on 20 June invaded southern France. By then the Battle of France was almost over. The Italian troops made only limited progress and made almost no strategic difference.

8. The Battle of France Lasted 46 Days

The Battle of France lasted only 46 days – from the German invasion of 10 May to the announcement of an armistice on 25 June 1940. German Blitzkrieg tactics and highly effective Panzer formations far outmatched the slow-moving French and Gamelin’s cautious strategy. The British, having far fewer troops in the fight, went along with the French plans, and found themselves cut off and forced to withdraw.

Paris fell on 14 June, and French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud, seeing the failure he had overseen, resigned on 16 June. His replacement, Marshal Philippe Pétain, immediately started suing for peace.

9. The Armistice was Signed in a Railway Carriage – Again

The armistice agreement was signed on 22 June 1940, with Hitler traveling from Germany for the event. The signing took place at the symbolically powerful site of Compiègne.

Compiègne had been the German headquarters in France during World War One, and it was there that they had signed the armistice of 1918. Hitler’s early political career was built on German resentment at the results of that peace. He made the French sign their own surrender in the same railway carriage in which the 1918 peace was signed, and then took the carriage to Germany as a souvenir. Five years later, in April 1945, it was destroyed rather than let the Allies recapture it.

10. There were 523,000 Casualties

The Germans suffered 157,000 casualties in the Battle of France, 27,000 of them dead. Their Italian allies suffered around 6,000 casualties.

The Allies lost over twice as many men, with 360,000 dead or wounded. A further 1,900,000 were captured.

Western Europe was now in the grip of the Axis powers, and the Allies had no land base on the continent.

Put on trial by Frances Vichy regime, which collaborated with Germany after the fall, Maurice Gamelin refused to answer the charges, sitting in dignified silence. He was imprisoned in France and Germany, and survived the war, living until 1958.