Throughout history, rivers have divided countries, territories, and armies. They’ve proved to be difficult obstacles, keeping invading troops at bay and keeping countries separated. Of course, rivers have also been lines to cross – the challenging obstacle to conquer in order to successfully gain more territory and crush the opposition.

Such was the case during World War II, as the Allied forces faced the Rhine River and the German lands that laid behind its eastern bank. As the war began to reach its final months, the Allied troops needed to cross the Rhine and secure the territory still held by the enemy. In order to successfully execute a river crossing, Operation Varsity was developed.

On the night of March 23, 1945, the Allied forces that had gathered along the Rhine launched their invasion. Hours later, the attack multiplied as the ground troops were aided by an impressive airborne operation that brought planes, paratroopers, and more soldiers. With more than 16,000 paratroopers and thousands of aircraft taking to the sky, this was Operation Varsity.

In just one day, this airborne effort helped the Allied troops secure victory on the ground, and take control of crucial German towns, villages, and strongholds. Operation Varsity was more than a success; it was a historic event, full of interesting strategy and impressive moments. Here are 10 facts you may not have known about this large-scale effort to bring World War II to an end.

1. The actual crossing of the Rhine River was led by the British; Operation Varsity was an Allied air attack meant to aid those on the ground.

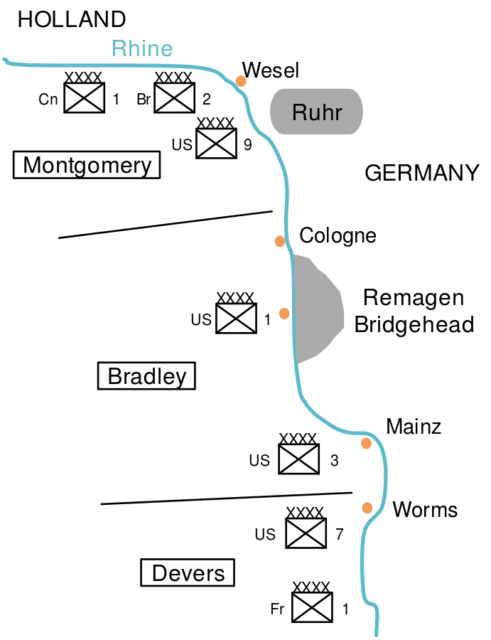

Although Operation Varsity was orchestrated by Allied Forces to secure territory and control in western Germany, those who participated in this operation didn’t actually cross the Rhine River. That ground-based effort was conducted under a different name: Operation Plunder. While Operation Plunder took place, the British 21st Army Group led across the river by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, Operation Varsity was launched in the sky. More than 16,000 American, British, and Canadian paratroopers and thousands of aircraft came together to help the ground troops secure the all-important land surrounding the Rhine.

Operation Varsity followed different orders and different plans than Operation Plunder, though the two were a combined effort. The plan was to disrupt a variety of German defense in order to secure territory quickly.

Operation Varsity was meant to support and help the Allied ground forces accomplish their goals.

Two divisions of the U.S. XVIII Airborne Corps were assigned specific villages and landmarks to capture; Schnappenberg, Hamminkeln, sections of the Diersfordter Wald, and three bridges along the River Issel were to be taken by the British 6th Airborne Division, while Diersfordt and the rest of the Diersfordter Wald were taken charge by the U.S. 17th Airborne Division. Once these airborne targets were secured, the airborne divisions were to hold them until the Allied ground troops joined them.

2. Operation Varsity was the first crossing of the Rhine River since Napoleon Bonaparte.

The combined efforts of Operation Plunder and Operation Varsity marked the first time any invading army crossed the Rhine in over a century – the last attempt to do so was led by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1805, and his crossing was a success.

3. General George Patton was specifically ordered not to cross the Rhine River.

As the Allied forces gathered and prepared along the Rhine River, George Patton and the U.S. 5th Division were quietly carrying out their own plan. Commanding General Omar Bradley ordered Patton to stay put; Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery was preparing to lead his division across the Rhine the next morning, and Bradley worried that any action by Patton would interfere with the entire operation’s success.

Patton, however, was hopeful that the Americans would be the first to cross the river and announce their success, so he gathered his men and took matters into his own hands. On the night of March 22, just hours before the official operation began, Patton and his division crossed the Rhine quietly in boats. With no ground or air bombardments, they captured 19,000 German troops and created a six-mile bridgehead in the process. Bradley, surprisingly, knew nothing of Patton’s crossing until the following morning when he had already achieved success.

4. The Allied Forces faced well-prepared German troops on the other side of the river – but they met less resistance than anticipated.

When the troops participating in Operation Varsity and Operation Plunder were gathering along the Rhine, not much was hidden from the German forces waiting on the other side. The German military knew that the Allied troops were doing more than simply increasing their presence; they knew an invasion was soon to come. So, not surprisingly, the Allied forces believed that the Germans would be quite prepared for the coming Rhine crossing.

It was expected that mortar and artillery guns were already trained and waiting at every potential river crossing location, and that elite troops would be manning these sites. However, when Allied troops took to the river and the sky, they met weaker resistance than they expected; even in heavily protected areas like the northern Ruhr River region, the German response was less destructive.

5. Operation Varsity contradicted all other airborne strategy used throughout World War II.

Operation Varsity made history as the largest single-lift airborne operation conducted in World War II, but that isn’t the only reason it became one of the war’s standout military maneuvers. In fact, it’s also notable because it was contrary to every airborne strategy used previously throughout the war. In an effort to reduce losses, the airborne troops dropped after the ground forces successfully crossed the Rhine River. Additionally, the airborne troops landed quite close to the troops on the ground – they dropped not far behind German lines, allowing them to connect with ground forces quickly.

This new airborne strategy came about after the somewhat disastrous Operation Market Garden, during which airborne forces dropped too far away to meet their counterparts on the ground and suffered great losses when attacked by German forces.

6. Some of the airborne divisions that participated had seen relatively little action in the war.

Although we often assume that successful military operations require greatly experienced soldiers, such isn’t always the case – and it certainly wasn’t the case in Operation Varsity. In the planning stages, three airborne divisions were selected to perform the operation: the British 6th Airborne Division, the U.S. 13th Airborne Division, and the U.S. 17th Airborne Division. Only one of these, the British 6th Airborne Division, had any wartime experience; the men participated in Operation Overlord at Normandy a year prior.

The other two divisions had far less experience. The U.S. 17th Airborne Division had never performed a combat drop, and the 13th Airborne Division had been far from any action, waiting in Britain and France since 1943.

7. Operation Varsity was the largest single day airborne drop in history.

Operation Varsity earned itself the title of the largest single day airborne drop in history – and that’s in addition to being the largest single-lift airborne operation in World War II. After Operation Plunder charged across the Rhine and secured multiple crossing sites along the eastern bank of the river, the efforts of Operation Varsity took off from England and France. 541 aircraft and their troops headed to the Rhine, along with 1,050 troop-carriers towing an additional 1,350 gliders.

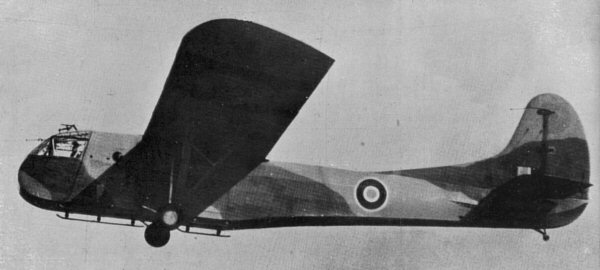

It truly was a massive effort; the 17th Airborne Division brought 9,387 troops in 836 C-47 Skytrains, 72 C-46 Commandos, and over 900 Waco CG-4A gliders, while the 6th Airborne Division added their 7,220 troops in 42 Douglas C-54 and 752 C-47 Dakotas, 420 Airspeed Horsa and General Aircraft Hamilcar gliders. As this incredibly large group made its way through the sky, it stretched across more than 200 miles – and, of course, it was accompanied by 2,153 Allied fighters.

8. The already-exhausted German forces were wiped out thanks to the air attack.

Operation Varsity was successful, and allowed the Allied troops to secure crucial areas within Germany – all of the original objectives of the operation were captured and held, and the entire effort was conducted in the span of a few hours. Perhaps the biggest advantage of all, as defending German Major-General Fiebig remarked, was Operation Varsity’s surprising speed.

Though German troops were gathered in the area and prepared for a coming Allied invasion, they had no idea just how large and fast it would be. The Germans were taken aback by the two airborne divisions, and it was the speed with the divisions landed their troops that overwhelmed the defenders. Major-General Fiebig also shared that the Germans were outnumbered and overpowered before the invasion even began; the troops were weakened by repeated battles with Allied forces, and Fiebig’s unit alone was left with only 4,000 soldiers.

9. Causalities occurred – but far fewer than expected.

It’s expected that every wartime operation will come with casualties, but Operation Varsity experienced fewer losses than military experts anticipated. Out of their original 7,220 troops, the 6th Airborne Division lost 1,400 men who were either killed, wounded, or missing in action. The losses of the 17th Airborne Division were similar, at 1,300 out of 9,650. The two divisions together captured about 3,500 POWs as well.

10. Though the operation was successful, notable mistakes were made.

Despite its overall success, Operation Varsity wasn’t without a few missteps. Pilot errors were the most prevalent – and the biggest mistake occurred when a pilot led a group of paratroopers into the wrong drop zone. The 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Edson Raff, was assigned to be the lead assault formation for all of the U.S. 17th Airborne Division. These paratroopers were to be the first American airborne unit to land on German territory, instead, things got a bit complicated.

The regiment and the troops it was leading into Germany were all meant to drop in Zone W, a clearing just a couple miles north of the town of Wesel. However, when the group arrived near Zone W, they met cloudy haze covering the ground, and the pilots were confused as to where to execute the drop.

With little direction, the regiment split into two groups – and the drop was performed in two different sites. Half of the paratroopers landed in Zone W, but Colonel Raff and nearly 700 paratroopers landed near the town of the Diersfordt. This was supposed to be a British drop zone; fortunately, no troops collided and the paratroopers were able to regroup and adjust quickly.