Operation Overlord and the D-day landings on June 6th, 1944 were supported by a massive assault of airborne infantry, both paratroopers and men in large military gliders. Results were very mixed. There were many casualties both in the air and for the often scattered soldiers who made it to the ground alive. There were many success stories, as well, of troops securing vital bridges, sabotaging German communications and equipment, and attacking the enemy.

This was not, however, the Allied force’s first use of an airborne assault. They had to learn through immensely painful trial and error, a process, that saw the largest friendly fire incident for the Americans at the time. This first major proving ground was the invasion of Sicily in July 1943, almost a year before D-day. Though the invasion was ultimately a success and paratroopers would be used in other major invasions, the horrors experienced by British and U.S. troops would not be forgotten.

Three separate incidents between July 9th and July 13th, 1943 resulted in an intensive reworking of how the Allied combined forces coordinated airborne infantry assaults. Two of them involved jaw-dropping friendly fire incidents and another almost lead to fights between British and U.S. pilots and glider troops.

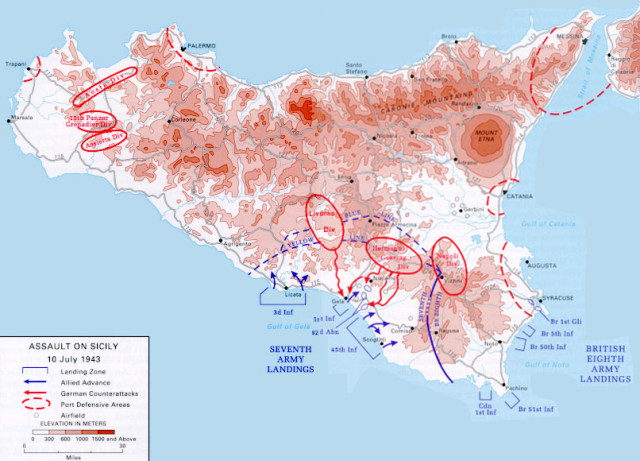

After dark on June 9th, the invasion of Sicily began, first with paratrooper and glider infantry, then by sea in the early hours of June 10th. The Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Allied force was General Dwight D Eisenhower. The U.S. Seventh Army, led by Lieutenant General George S. Patton, landed on the South coast while the British and Canadian Eighth Army, led by General Bernard Montgomery, landed on the Southeast coast.

Luckily, the U.S. paratroopers, mostly from the 505 st Parachute Infantry Regiment in the 82nd Airborne Division, avoided any calamitous friendly fire incidents this time around. They were, however, very scattered upon landed and often missed their drop zones by quite a ways. Though they did manage to harass the Italians and Germans a great deal. The British 1st Air-landing Brigade, however, fared far less well.

Over 2,000 British troops took off in 136 Waco (American built) and eight Horsa (British built) military gliders towed by British and U.S. bombers. While flying to their targets and encountering bad winds and anti-aircraft fire, the bombers climbed, taking evasive action.

Confusion spread throughout the formations and 65 gliders were released from their tow lines too early. They crashed into the sea and killed 252 men. Of the remaining gliders, some were taken back to their bases in North Africa and only 71 made it safely to Sicily. Of those lucky 71, only twelve landed close to their target.

Upon returning to base, British and American pilots, officers, and troops involved in the incident had to be separated due to tensions and accusations— and violence was feared.

Throughout June 10th and 11th, Allied forces landing on the beaches and meeting up with the airborne troops secured a foothold in Fortress Europe. On the night of June 11th, another drop of U.S. paratroopers was planned and executed, again from the 82nd Airborne, but now the men of Major General Matthew B. Ridgeway’s 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

From Tunisia, 144 C-47s and C-53s carrying some 2,000 U.S. paratroopers flew towards the South coast of Sicily. Word had been sent to the Navy informing them of the operation and to the forces on land. Many on the ships would later claim the message had not been received. Furthermore, they had been attacked by German bombers throughout the day and were frayed from battle.

Whatever or whomever was to blame pales in comparison to the terror that unfolded when anti-aircraft gunners on shore and on the ships opened fire on the planes carrying their fellow soldiers.

The reaction of onlookers from the time reveal the catastrophe in plain and striking words: “Patton could only stare in horror, repeating, ‘Oh, my God,’ over and over while Ridgeway cried. Anti-aircraft gunner Herbert Blair later wrote, ‘Only then does the dreadful realization descend like a sledgehammer upon us. We have wantonly, though inadvertently, slaughtered our own gallant buddies. I feel sick in body and mind.’”

Allied planes were exploding in the skies above their heads, shot down by their own comrades. The sight was heartbreaking, barely comprehensible.

Over 300 men were killed in the bloody mistake. One plane that had turned around and made it back to Tunisia had more than 1,000 holes shot through it.

The final, awful incident of the airborne landings on Sicily happened late on the 12th/early on the 11th of June. 1,856 men of the British 1st Parachute Brigade were being carried in well over 100 planes to land inside the Southeast coast of Sicily. Thirty-three of the planes accidentally went off course, flying over a convoy of Allied ships. The sailors had been expecting a German air raid and opened fire.

Four planes along with their contained soldiers went to the bottom of the sea. The planes that survived, along with those that didn’t stray from the flight plan, encountered heavy enemy anti-aircraft fire in Sicily and lost another 37 craft. All told, only 39 planes managed to drop their troops within a half mile of their target.

Following the invasion of Sicily, considerable training was implemented in the Army, Air Force, and Navy of Britain and the U.S. Glider pilots were subjected to much more rigorous training for missions, ships crews were instructed in aircraft recognition, and Allied planes were painted with three, large white stripes under the wings for identification. Everybody prayed such terrible accidents would never happen again.

By Colin Fraser for War History Online