“The conventional wisdom of D-Day is that there were no Black soldiers who landed on those beaches, but the truth is that there were almost 2,000 Black soldiers who landed by the end of the day June 6, [1944].” Linda Hervieux, author of The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, at Home and at War. The troops Hervieux is talking about: the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion.

Maj. Gen. Peter Gravett, US Army (Ret), the first African-American division commander in the Army National Guard, highlights the accomplishments of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion and three other African-American Army units in his latest release, Battling While Black: General Patton’s Heroic African American WWII Battalions.

African-American servicemen during the Second World War

The US Army never intended to build and deploy Black battalions during the Second World War, and while they’d go on to serve overseas, in battle after bloody battle the military hardly recognized them as humans, let alone official combat units. African Americans were merely there to prove a “technical presence” in the Army – just something to quiet the loudening voices of Black leaders uniting to disrupt popular opinion that they had no right to fight for their country.

Little did the US military know that the men of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion would make ignorance-shattering history by landing on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day.

Balloon battalions in the US military

More than 30 barrage balloon battalions were trained at Camp Tyson, Tennessee during World War II, including four African-American units: the 318th, 319th, 320th and 321st. White soldiers made up units 301 through 317.

War balloons were first established under the command of the US Army Air Corps (USAAC). One of the largest battalion-size organizations in the Army, each unit boasted an average of 1,100 men and more than 50 barrage balloons.

Initially, these units were “coast artillery barrage balloon battalions,” but the first half of the name was dropped on July 15, 1943, after the anti-aircraft command took over the balloon program, changing them to “anti-aircraft barrage balloon battalions.”

Undergoing training for action overseas

Those selected to join one of the barrage balloon battalions underwent basic training, after which they moved on to a six-week regimen that taught them how to handle the barrage balloons in battle. This included filling them with hydrogen gas; attaching explosives to their cables; camouflaging them; and maintaining and repairing them.

Once they’d completed this portion of their training, the recruits underwent a 12-week course on weather forecasting, a necessary skill, given how vulnerable the balloons were to the effects of Mother Nature.

320th Barrage Balloon Battalion and D-Day

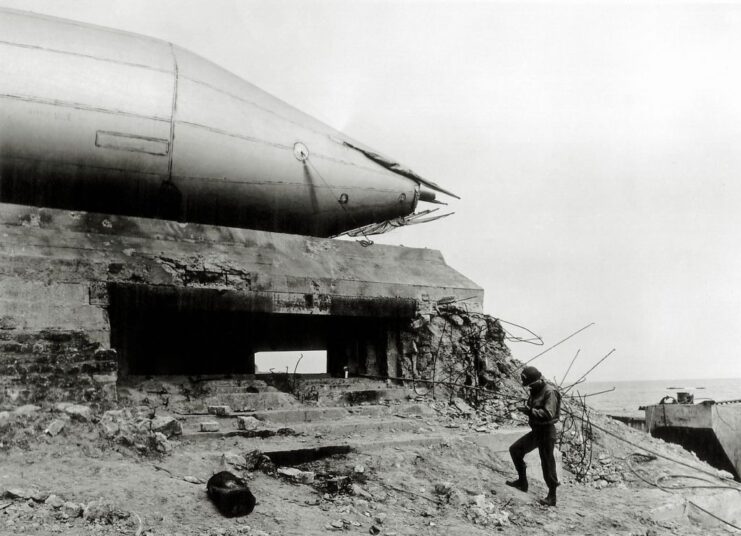

After their training, the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion received its first assignment: landing on two beaches – Utah and Omaha – on D-Day. Their job was to protect the infantry, armored and naval assault with hydrogen-filled barrage balloons, which would be raised 200 feet into the air.

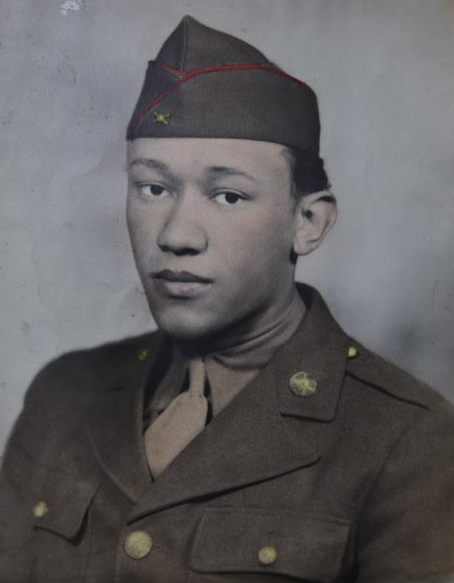

At 9:00 AM on June 6, 1944, five medics with the 320th landed on Omaha Beach, with crews of three-to-four men joining them shortly after. Cpl. Waverly Bernard Woodson, Jr. was among them. He was injured when his Landing Craft, Tank (LCT) hit a sea mine and was, then, struck by an artillery shell.

Despite his injuries, Woodson continued to perform his duties, conducting an amputation, setting limbs and removing bullets over a 30-hour period. He even revived three men via artificial respiration. His efforts on D-Day are believed to have saved 200 soldiers, and he was recommended for the Medal of Honor by Gen. John C.H. Lee. He, instead, received the Bronze Star and Purple Heart.

The remainder of the 320th faced heavy enemy fire, which destroyed the majority of their barrage balloons. That being said, 20 did make it ashore at Omaha Beach, with one making it into the air by 11:15 PM that night. By the next morning, another 11 were aloft, with replacements brought in as they were shot down by enemy fire.

320th Barrage Balloon Battalion’s service following D-Day

By August 1944, the skies over Normandy were quiet, with Allied aviation assets now controlling the skies and the Luftwaffe down to a small number of fighters. When September rolled around, the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion was redeployed for other tactical assignments throughout the country during its remaining 140 days in France.

Later that year, Battery A moved to the tip of the Cotentin Peninsula to fly a barrage at Cherbourg, the key port city captured by the Allies three weeks after D-Day. The remaining three batteries stayed on the beaches, their balloons soaring over Omaha and Utah until early October when deteriorating weather prevented ships from landing.

More from us: Bell P-63 Kingcobra: The American Fighter-Turned-Soviet Tank Buster

Following their service in the European Theater, the 320th underwent training at Camp Stewart, Georgia for their anticipated deployment to the Pacific. However, before they could make it there, the Japanese surrendered, ending the Second World War.

Maj. Gen. Peter J. Gravett, US Army (Ret) is the first black division commander in the Army National Guard and the son of a World War II Tuskegee airman enlisted soldier. Gen. Gravett also served four years as the Secretary, California Department of Veteran Affairs in the Governor’s Cabinet.

Gen. Gravett’s lifelong interests in World War II history compelled him to write, Battling While Black: General Patton’s Heroic African American WWII Battalions. He began his military career by enlisting in the then-segregated California Army National Guard. He holds a Master’s degree from the University of Southern California and executive diplomas from the University of Virginia and Harvard University. He is also a graduate of the FBI National Academy and the Army War College.