During the 1930s, many Western politicians and military commanders were complacent about the threat posed by Germany and Japan. Japan seemed far away, a Chinese problem. Germany’s Nazi party was belligerent in its outlook but surely not likely to start another massive war.

That complacency was part of the reason the Axis powers remained largely unopposed for so long. It allowed them to expand and leave the Allies unprepared for the coming war. While Germany experimented with the latest weapons and planned for the future, Allied leaders were bogged down in the thinking of the past.

Fortunately, a few military men were looking to the future.

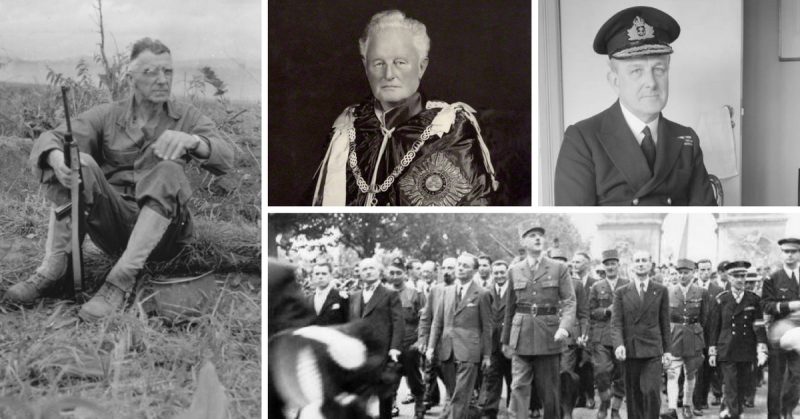

Charles de Gaulle

Remembered as the statesman who led the Free French through WWII, de Gaulle’s position before the war was very different.

As an officer in his 20s during WWI, de Gaulle proved he was a bold leader. He was wounded in combat three times, taken prisoner by the Germans, and made several escape attempts.

Between the wars, de Gaulle served as both a field commander and a staff officer. Using a mixture of theoretical and practical knowledge, he drew on lessons learned from the first war and changes in technology. They became the basis of several books, starting with Discord Among the Enemy in 1924. Outspoken in his opinions, he often clashed with his superiors. Political patrons saved his career.

De Gaulle argued for a more professional standing army and greater use of armored fighting vehicles. He wanted tanks concentrated into potent strike forces, rather than scattered around. He also advocated motorized infantry to make the most of any breakthroughs. As Hitler came to power in Germany, de Gaulle argued strongly for rearmament and modernization of military equipment.

Ironically, de Gaulle’s views were more influential among his enemies. His Toward a Professional Army sold ten times as many copies in Germany as in France and was studied by Hitler. In France, de Gaulle was sidelined by a military that had learned very different lessons – ones which turned out to be far less valuable.

When Germany invaded France in 1940, de Gaulle finally had his chance to put his ideas into practice. He was responsible for one of France’s few successes against the invaders. It also gave him the recognition by his superiors that had often been lacking. When France fell, he fled to Britain. There he rallied the Free French to continue the fight.

Vinegar Joe Stilwell

The American General Joseph Stilwell, widely known as Vinegar Joe, was one of the strongest personalities of WWII. His short temper and colorful language had long made him stand out and, like de Gaulle, he clashed with his superiors. He was smart, a capable leader, and had no patience for inefficiency or stuffiness.

Gifted in languages, Stilwell served on and off in the Philippines and China throughout his career. While stationed in China, he scorned the life of leisure and cocktail parties that many expatriates enjoyed. Instead, he acted as a supervisor on public works and traveled the country, learning about the state of the region. He saw the suffering of the Chinese as first civil war and then Japanese invasion tore the country apart. Stilwell became one of America’s top experts on China.

Having witnessed the Rape of Nanking in 1937, when the Japanese massacred 40,000 civilians, Stilwell became focused on Japanese aggression and brutality. He argued that America would have to side with China to stop the Japanese. He also identified the largest problem in doing so – the unreliability of the Chinese leadership.

In 1940, Stilwell was brought home. He spent the next year determinedly readying troops for the war he knew was coming. While many in America wanted to stay out of the fight engulfing the world, Stilwell knew it was impossible. His insight and energy helped prepare an unready America for war in Asia.

John Henry Godfrey

Admiral Godfrey became Britain’s Director of Naval Intelligence in 1938. He had been put in charge of a vital and neglected area of work. Since WWI, the British had assumed intelligence gathering and analysis could just be picked up again when it was needed. However, the skills and processes necessary to do so had not been maintained. A lack of insight into the German military was both a symptom of complacency and a cause of it. Without proper intelligence gathering, the British did not know how powerful their opponents were becoming.

Godfrey’s predecessor, Admiral Troup, had created the Operational Intelligence Centre (OIC). Godfrey built upon it. Although he did not know much about intelligence, he saw the need to employ men who did. He created an organization that could analyze incoming information and link that knowledge to action. By the start of WWII, the Royal Navy’s intelligence gathering service was still learning how to operate, but it was the best on the Allied side. It would lead the way in rebuilding military intelligence.

William James

One of the other key figures in rebuilding British naval intelligence, Admiral James became Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff in 1936. Seeing the information coming in about the Spanish Civil War and the Abyssinian War, he realized that the Naval Intelligence Division lacked the resources and skills to collate and analyze the information. Having been head of the cryptographic team in Room 40 during WWI, he realized how important it could be.

It was James’s advocacy that led to the establishment of the OIC and the recruitment of the skilled specialists who would lead its increasingly impressive work.

Sources:

Ralph Bennett (1999), Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the War with Germany 1939-1945

Richard Holmes, ed. (2001), The Oxford Companion to Military History

David Rooney (1999), Military Mavericks: Extraordinary Men of Battle