During the Second World War, military intelligence came into its own in a way it never had before. The increasing speed, scale, and complexity of operations meant there was more to learn than ever. New techniques and renewed interest in old ones enabled the combatants to learn a lot about each other.

Intercepted Signals

During the First World War, electronic communication had been through telephone lines. These could only be intercepted if the cable was discovered.

In the Second World War, it was different. Radio communication was vital to connecting armies across a continent. It was also vulnerable to interception, as enemy operators could pick up the radio signals.

To counter this, both sides used codes and encryption to disguise their messages. In some cases the codes were broken, most famously with Ultra, the interception and interpretation of German Enigma signals by the British.

If decoded and translated in time, signal intelligence provided information about an enemy. A planned attack might be known about before it happened.

Photographic Reconnaissance

Aerial photographic reconnaissance had been born during the First World War. As planes flew across the trenches, their crews took photos of enemy equipment and emplacements. Experts then interpreted them back at HQ.

Although this area had been neglected between the wars, it came into its own again. As before, steps were quickly taken to improve the skills, techniques, and equipment available.

Photographic reconnaissance provided information about enemy supplies and formations. Interpreting it enabled analysts to predict where attacks were likely to occur, and where to direct bomber strikes.

Captured Equipment

There was no better way to understand enemy equipment than to lay hands on it.

On land, this mostly happened during moments of victory, when advancing troops could seize abandoned weaponry.

Where it came in particularly useful was in the aerial war. If a plane was shot down over enemy territory, it could be examined. This was one of the ways in which the British came to understand the German Knickebein bomb targeting system; through equipment found on a downed plane.

Captured material occasionally extended to other forms of intelligence, such as code books and orders. These lucky finds could create unexpected insights.

Agents

The long tradition of planting spies behind enemy lines continued in the Second World War. These could be among the most capable operatives, highly trained and able to seek out specific information. When successful, they often went unnoticed and unremembered.

The capture of enemy agents was as valuable as the work of friendly ones. Two British officers, Major Stevens and Captain Best, were caught by the Germans at Venlo on the Dutch-German border in November 1939. Under interrogation, they revealed details of other operatives, allowing the Germans to destroy much of Britain’s intelligence network on the continent.

Unknown to the Germans, their spy network in Britain was profoundly compromised. The British had identified every German agent on their soil at the start of the war. Many were neutralized, and those left in place were fed false information to give to the Germans.

Resistance Networks

Every country occupied by the Nazis had some resistance operatives. These proved useful intelligence sources for the Allies. Norwegian resistance fighters were among the sources of information that allowed the British to sink the Bismarck, the most powerful battleship in the world.

In Czechoslovakia, the resistance had ties to British intelligence. The British-trained Czech operatives were provided with equipment such as radio sets. In return, Britain received news about events in Czechoslovakia. A British-backed action by agents of the Czech government in exile, acting on intelligence from the local resistance, assassinated the senior Nazi Reinhard Heydrich.

Defectors

There were defectors on both sides, and they provided useful sources of information. On arrival, they were likely to be questioned at length about what they knew about military, industrial, and political matters.

Defectors could be useful, but they could also be problematic. A person who was contented and close to the center of power was unlikely to defect. Those who did had often been marginalized so were less well informed than their peers and prone to bias.

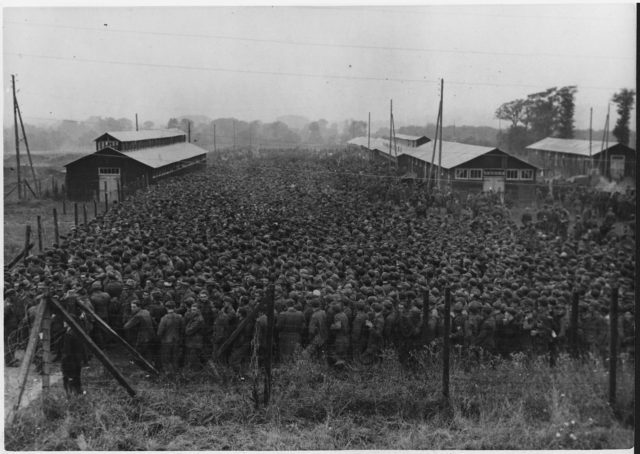

Prisoners of War

In the war, there were many prisoners. Whether soldiers, sailors, or airmen, all knew at least a little about the military operation of their armed forces. The more senior they were, the more valuable their information was likely to be.

Interrogation of prisoners was common. Despite the rules of war, it sometimes extended to acts of cruelty and torture, although the nature of such actions means it will never be known how common they were. Some men, broken by defeat, shared information willingly, others far less so.

Some shared information without even realizing it. Hidden microphones in a prisoner of war camp allowed guards to overhear conversations between inmates. This was another of the ways the British learned about the German Knickebein system; captured airmen talking about bomber apparatus that used radio pulses.

Friendly Neutrals

Official neutrality did not mean not playing a part in the war. As the Americans showed with their trade in arms to Britain, a country could seek to influence the outcome of the war without being drawn into the fighting.

Sometimes, neutral powers could be useful in intelligence gathering. Sweden, which remained neutral throughout the war, helped in the detection of the Bismarck. When a Swedish vessel spotted the German battleship, the location was passed to the head of Swedish intelligence. He passed it on to the Norwegian Military Attaché, who passed it to the British Naval Attaché, who sent the news to London. This game of Chinese Whispers let the Swedes help their Norwegian neighbors while maintaining every sign of neutrality.

Sources:

Ralph Bennett (1999), Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the War with Germany 1939-1945.

Russell Phillips (2016), A Ray of Light: Reinhard Heydrich, Lidice, and the North Staffordshire Miners.