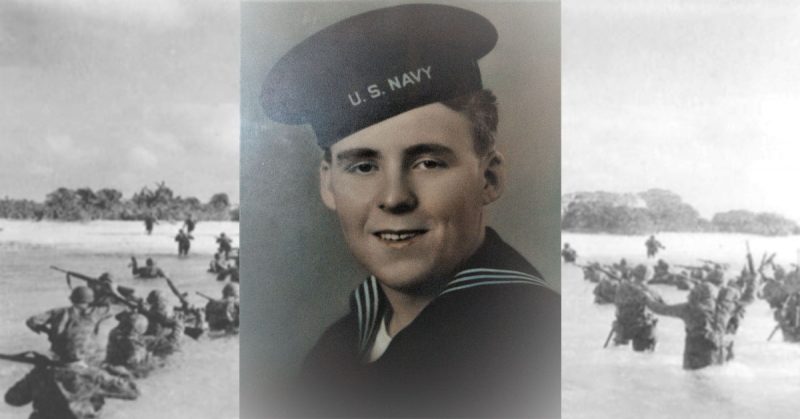

Decades before he was inducted into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame for his success as a high school football coach, John “Pete” Adkins collected a treasure trove of experiences with his first team—the U.S. Navy—in World War II. These days, however, when it comes time to assemble a team, it is in support of veterans’ events to honor those who never made it home from the war.

A 1943 graduate of Mexico High School in Mexico, Missouri, Adkins and a small group of friends decided to enlist in the U.S. Navy before the military draft process made the decision for them.

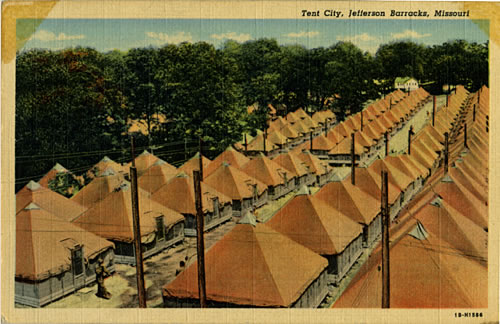

Adkins reflected, “We went over to enlist at a recruiting office in Mexico and they sent us to Jefferson Barracks [St. Louis] for our induction in July 1943. Then, a day or so later, they put us on a troop train and sent us to Farragut, Idaho, for boot camp.”

Established in 1942 as the Farragut Naval Training Station, Adkins said it appeared as though “they took a hillside, some flatland and then carved a naval base out of it.”

For the next eight weeks, he and his fellow recruits underwent their initial training. When many of the trainees began to depart for additional training at other locations, Adkins remained at the Idaho base for another eight weeks to become a signalman—a specialty, he recalled, that the Navy selected for him.

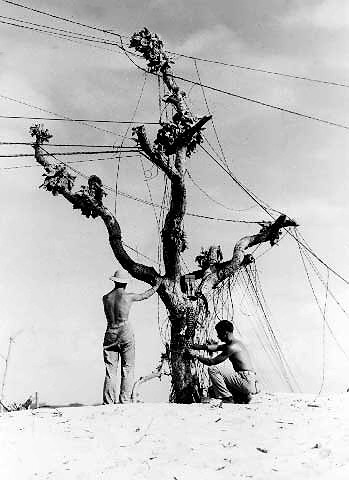

“Everything in signal training was visual; we didn’t use any radios for communication,” said the veteran. “We used flags and flashing lights to signal in Morse code. It was our job to learn to direct ship traffic in and out of harbors, making sure they knew where to moor, when to depart and so forth.”

Much of their training, he recalled, was spent in the classroom learning skills such as communicating letters of the alphabet using flag signals known as “semaphore.” Additionally, they spent time in a mock signal tower demonstrating they had acquired the skills necessary to direct harbor traffic.

From there, the untested sailors were transferred to San Pedro, California, to apply their new skills in a live training environment.

“We were there for about 4 or 5 weeks,” he said. “They had a signal station in the harbor and they indoctrinated us into doing live signal work by directing ships.”

They spent additional training time in San Francisco before traveling to Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay, where they received an issue of uniforms, weapons and equipment. They were then sent into the mountains for a brief period of training by the Marines, much of it focused on weapons familiarization, before traveling to Shoemaker, California, to board a troop ship.

Following an overnight stop in Pearl Harbor, Adkins and his fellow signalmen sailed for the Marshall Islands in the central Pacific. They arrived in late March 1944 on the Eniwetok Atoll, which had been the site of a brutal battle a month earlier.

Eniwetok “was defended by a garrison of 3,400 men,” wrote Trevor Dupuy of the Japanese occupation in his book Asiatic Land Battles: Japanese Ambitions in the Pacific. He added, “A combined landing force of Army and Marine units, totaling nearly 8,000 men, landed there on February 19 [1944]. The [Japanese] defenders were overwhelmed in four days of vicious fighting.”

“The island was said to be the largest natural harbor between Hawaii and Japan,” Adkins said. “When we got there in March, the Seabees had already built a signal tower that rose above a stockade that held a small group of Japanese prisoners of war.”

As the former sailor explained, the Japanese prisoners were soon moved elsewhere but he remained on Eniwetok, spending the next two years applying the signal instruction he had received stateside by directing naval traffic in the harbor.

“About the only time I left Eniwetok during the two years I was stationed there was for 11 days of leave in Hawaii—that was it,” Adkins affirmed. “We lived in a tent city that entire time and we had outdoor showers set up on the beach.”

In the early days of August 1945, an assortment of naval vessels began to assemble in the harbor, leaving Adkins and his fellow signalman to speculate that a major military operation was in its beginning stages.

“We found out several days later that the ships were there for the planned invasion of the Japanese mainland,” Adkins said. “But they ended up dropping the atomic bombs on Japan and the war was over.”

Remaining on Eniwetok until March 1946, Adkins returned to the United States and was discharged on April 3, 1946. After going home to Mexico, he married the former Lorraine Fenner in 1948 and utilized his G.I. Bill benefits to earn his master’s degree in education.

As the years passed, he became head football coach for Jefferson City High School, retiring in 1995. Throughout the course of his 45-year career, he compiled a 405-60-4 record, resulting in his induction into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame in April 2013 for being the most successful high school football coach in the nation.

His victories on the gridiron notwithstanding, Adkins values his service in the U.S. Navy and maintains it helped instill the lifelong aspiration to recognize his fellow veterans while also refining many positive qualities he has embraced throughout his career.

“The military does a lot for a person—the discipline, the work ethic and the fact that we had to learn to live very sparingly,” Adkins said. “I can tell you, living in a tent for two years will make a believer out of you and made me appreciate home.”

He added, “Since that time, I have always remained active in veterans’ events to help honor those men who were killed taking that island before I got there in WWII. And when you go to a veterans’ function, it’s special because we all have something in common…we have all developed a respect for those who have served.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.