In October 1939, Adolf Hitler signed a decree that enabled Nazi Germany to forcefully euthanize patients who they deemed were “unworthy of life”.

After the war, the law was classified as Action T4. The name stands for Tiergartenstrasse 4, the infamous address of the Chancellery Department in Berlin, which employed physicians designated to conduct the euthanasia program.

The head of the Chancellery was Phillip Bouhler who worked together with the Fuhrer’s personal physician, Dr. Karl Brandt to carry out the program. Hitler’s eugenics policy promoted his interpretation of the Darwinist law of nature ― the survival of the fittest ― emphasized within the Nazi ideology.

Put that to a state-controlled level and you get mass murder of thousands of physically and mentally challenged people, including children. Hitler’s Action T4 used the Greek word “euthanasia” (literally: good death), as his name for his policy. Using various means, such as fake death certificates, the deception of the victims and their families and widespread cremation the Nazi extermination strategy of the weakest and more vulnerable in their society was hidden.

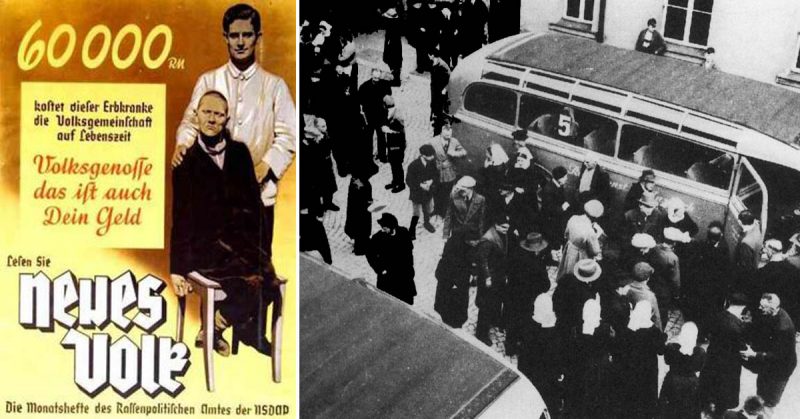

To understand how this happened, we need to understand the context of the time. Eugenic theories (the science of improving the genetics of humans) were indeed popular in Europe and the United States during the first half of the 20th century.

Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States passed laws that endorsed sterilization of individuals deemed to carry hereditary diseases, especially ones concerning the person’s mental health, such as schizophrenia. On these grounds, Hitler made sterilization legal in 1933 passing the “Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring” that involved people who had hereditary diseases such as schizophrenia, epilepsy, Huntington’s chorea and “imbecility.” The law also impacted on those with chronic alcoholism and a history of social deviance.

They targeted inmates of nursing homes, asylums, prisons, care homes and special schools for disadvantaged children. An estimated number of sterilized persons is 360,000 in a period between 1933 and 1939. In 1937, a shrinkage in the workforce occurred, so the sterilizations were pushed back. In 1939, war conditions forced the Nazis to reconsider their policy.

Hitler knew he couldn’t implement the euthanasia law before the war, but when the war effort started, a lot of popular support went to the idea of emptying the hospital beds reserved for the terminally ill or patients in psychiatric wards.

Although the law was passed in October 1939, a “test subject” was committed in July that same year. Karl Brandt conducted a “mercy killing” of a blind, mentally challenged boy as an answer to a plea submitted by the boy’s family.

The boy was killed in September 1939 before the decree was in effect. This was never legally approved, for the entire program relied solely on a letter written by Hitler and not on an official Fuhrer’s decree. Hitler deliberately bypassed Health Minister Conti and his department, who might have raised questions about the legality of the program.

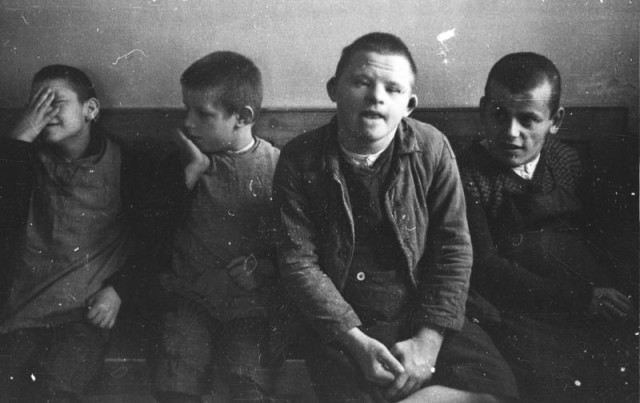

After this, the Reich Committee for the Scientific Registering of Hereditary and Congenital Illnesses was established as an institution for monitoring and registering any newborns with certain defects. The secret killing of infants began in 1939 and increased after the war started. By 1941, more than 5,000 children had been killed.

There were six extermination centers, established on the grounds of existing psychiatric hospitals: Bernburg, Brandenburg, Grafeneck, Hadamar, Hartheim, and Sonnenstein. These murders played an important role in creating the Final Solution policy and the Holocaust. Thousands of brains were taken from victims of euthanasia and used for so-called “medical” and “scientific” purposes.

Nazis used various deceptions when dealing with parents and legal guardians, especially in Catholic areas, where the families showed a lack of cooperation. Often, they would lie to them, saying that the children were being sent to special institutions where they would receive advanced medical treatment.

The children were indeed sent to special institutions, where they met their demise. They were kept for a few weeks for “assessment” in which it was determined whether or not the child is “worthy of life.” Those who didn’t pass were injected with a lethal poison, phenol. The cause of death was often claimed to be pneumonia.

As the war progressed, a parent or guardian’s consent was no longer deemed necessary, and the killings were done much more quickly, removing the “assessment” part completely. The parents who rebelled were often threatened with being sent to labor camps. The families were denied visiting rights due to wartime regulations. This practice lasted until May 29th, 1945, when the last child was murdered, three weeks after the war ended. The child’s name was Richard Jenne.

The same treatment was implemented on adults. The first adults who suffered this fate were Poles in 1939, during Operation Tannenberg, which was a genocidal act that intended to ethnically cleanse Polish population in Western Poland so that it could be inhabited by German settlers.

All hospitals and mental asylums in the territories annexed in 1939 were emptied by killing more than 20,000 patients during the first year alone. Some of the first gassing experiments were conducted in Poland, using hospital and mental asylum patients as victims in 1940.

With the arrival of the first military casualties, hospitals in Germany needed more space. In the initial phase of cleansing, more than 8,000 patients were murdered in Pomerania and East Prussia so that the wounded soldiers could be accommodated.

The gassings were then conducted in Germany, in Brandenburg Centre, under the supervision of Victor Brack who became the chief organizer of the Euthanasia program. The Nazis started using bottled pure carbon monoxide. Dr. Brandt declared during his trial in Nuremberg that this was “a major advance in medical history.”

Besides the gas chambers, experiments were conducted in utilizing the gas van, invented by the Soviet NKVD before the war and popularly called Dushegubka. Some doctors managed to save their patients by cooperating with the families. Some were declared sane, to avoid death, but it was a risky practice since the SS often inspected the program. The wealthier could afford to transfer to private clinics which were out of the reach of the T4 program.

The official duration of the program was from 1939 to 1941, but the Nazis continued with it throughout the war. The number of victims is hard to establish. In the two-year period, 70,273 people lost their lives and records exist to confirm this. Historians estimate that the total figure exceeded 200,000.