During WWII Juan Pujol Garcia played an important role in deceiving Nazi Germany about where the D-Day landings would occur. In gratitude, the Nazi’s awarded him an Iron Cross Second Class – one of Germany’s awards for bravery or other military contributions.

Pujol was a Spaniard who hated Communism, Franco’s Fascism, and Hitler’s Nazism. His solution was to become a British spy, but they refused him thrice. It was hard to do otherwise. Pujol was born to a prominent family who fell on hard times during the Spanish Civil War, forcing him to become a chicken farmer. But that didn’t do too well, either.

Undeterred, he decided to spy for the Germans so that the British would take him seriously. Pretending to be a Spanish government official who was sympathetic to the Nazi cause, he got in touch with a German agent in Madrid.

The British had an effective and extensive spy network on the continent, but the German secret service (the Abwehr) did not have one in Britain – though not for lack of trying. They had sent spies to Britain, but all had been caught and either executed or turned into double agents.

Desperate to have more spies on British soil, the Abwehr therefore accepted Pujol. They trained him in basic espionage, gave him a codebook, put him on their payroll, codenamed him Arabel, then sent him to Britain to recruit more agents.

Pujol instead went to Lisbon, Portugal where he got to work. Visiting the Lisbon library, he created fake reports based on a Spanish translation of the Frommer’s Guide to England (a tourist manual), magazines, reference books, railway schedules, maps, and newsreels.

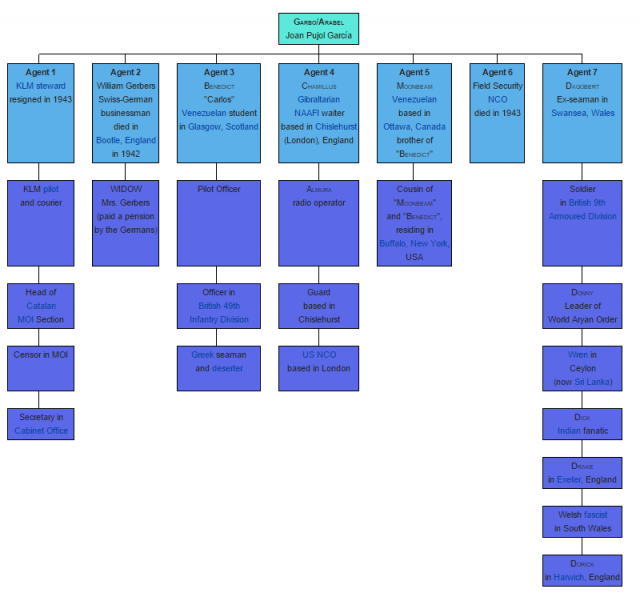

He also invented a vast network of non-existent spies. At its peak, they numbered 27, including a Swiss banker in London, a Venetian dock worker in Glasgow, and a KLM pilot who flew the route between Britain and Portugal. The latter explained why Pujol’s reports came from Lisbon – it was the pilot who flew them from London to Portugal, then mailed them from a local post office to the Abwehr.

Though none of these reports would have passed close scrutiny, the Abwehr apparently was not an effective organization so they never caught on. After the war, former Abwehr agents explained that it was better to send in numerous false reports than few or none at all. The alternative was to be sent to the front. On top of that, having failed to bring Britain to its knees, Germany was completely dependent on any information that Pujol sent them.

He sent so many reports that the British eventually intercepted them. Agents at Bletchley Park (where the British intercepted and decoded enemy transmissions) finally began hearing about a German agent in Britain, so they began looking for him – not realizing their man was on Portuguese soil.

The US entered the war in 1942, so Pujol approached them in February offering his services. The Americans saw Pujol’s potential and recommended him to the British, but they remained skeptical. It was only when Pujol sent the German navy on a wild goose chase looking for a non-existent convoy that the British finally took him seriously.

Pujol was relocated to Britain on April 24 and codenamed Garbo, even though he still didn’t speak English. To solve this, Pujol was assigned to Tomás Harris, a British secret service officer who did. The two men continued sending their reports to a post office box in Lisbon, producing so many reports that the Abwehr stopped trying to recruit more spies.

The intelligence they produced was largely fictitious, but contained enough genuine material to convince the Germans of Pujol’s effectivity. On 8 November 1942, for example, the British and Americans launched a joint invasion of French North Africa called Operation TORCH.

Pujol informed the Abwehr of the attack after it had happened, but the British had postmarked the letter to make it look like he had sent it before. After Operation TORCH, the Germans demanded a faster form of communication, so Pujol “recruited” a radio mechanic.

In cases where Pujol failed to give valuable information, he would claim that the agent responsible had died or was caught. In 1943, for example, a large British fleet set off from the northwest coast of England. To explain why he wasn’t able to report that, Pujol said that his man in Liverpool had died. To support this story, the British created an obituary for the non-existent spy which they published in the local paper.

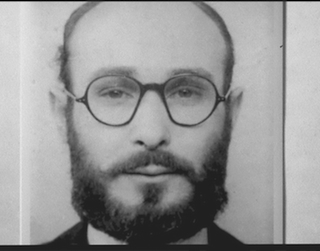

At the start of 1944, the Abwehr told Pujol that they expected a large-scale invasion of France. They were right, but it was necessary to let them believe it would happen at Pas de Calais instead of at Normandy, where they actually planned to land.

Pujol did such a good job that when the invasion happened on June 6, Hitler was convinced it was a diversion. He therefore held back two armored divisions and 19 infantry divisions at Calais, still believing that the main attack would come from there.

To ensure that no German reinforcements went to Normandy, Pujol sent another report on June 9 giving detailed accounts of a larger unit in England about to attack Calais. He was again believed, so the German divisions at Calais stayed put till August.

But there was a price. A week after D-Day, the Germans began launching their new V1 flying bombs across the channel into Britain. Many bypassed the British air defenses, hitting London.

They asked Pujol if they hit anything and to give them coordinates so they could fine-tune their aim. To maintain his cover, Pujol had to give them real coordinates so they could hit actual targets. While there were casualties and damage, his information at least minimized them.

Directing where those bombs fell was Pujol’s last act. After the war, he returned to Madrid where German agents told him that he had been awarded the Iron Cross on 29 July 1944. On November 25 that year, he also received a Member of the Order of the British Empire award from King George VI.

Pujol is, therefore, the only one to have received awards from both sides for his services in WWII.