When the Allies invaded Normandy in June 1944, one of the most important advantages they had was their air power. The Royal Air Force (RAF) and the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) played a critical role in the Overlord campaign which began the liberation of Nazi-occupied Europe.

Preparation

The work of fighter pilots and bomber crews began long before ground forces crossed the Channel. From early in the war, Allied bombers had set out from Britain to pound German infrastructure and industry, undermining the Axis war economy. Under the command of Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris (RAF) and General Carl “Tooey” Spaatz (USAAF), the bombers flew day and night against Germany.

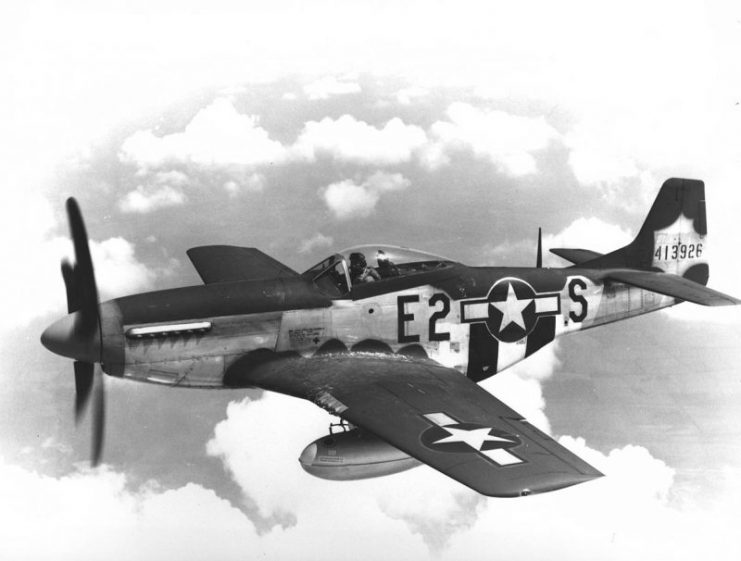

Early in 1944, Spaatz turned his focus onto Germany’s air fleet. Fortress and Liberator bombers attacked aircraft factories. This was not directly effective in weakening the Luftwaffe but did the job by other means. Attacking in daylight, the Americans needed fighter cover, and their deadly Mustang P-51 fighters destroyed so many intercepting planes that the Luftwaffe was left seriously short.

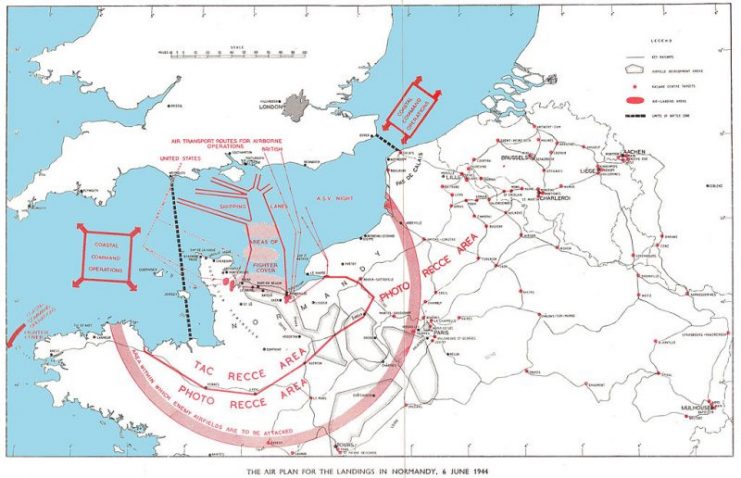

In the weeks leading up to the invasion, the focus shifted onto bombing the coast of northern France. Attacks were launched not just close to the invasion site but in other likely areas. As a result, German defenses were weakened and their troops distracted from the real targets.

D-Day

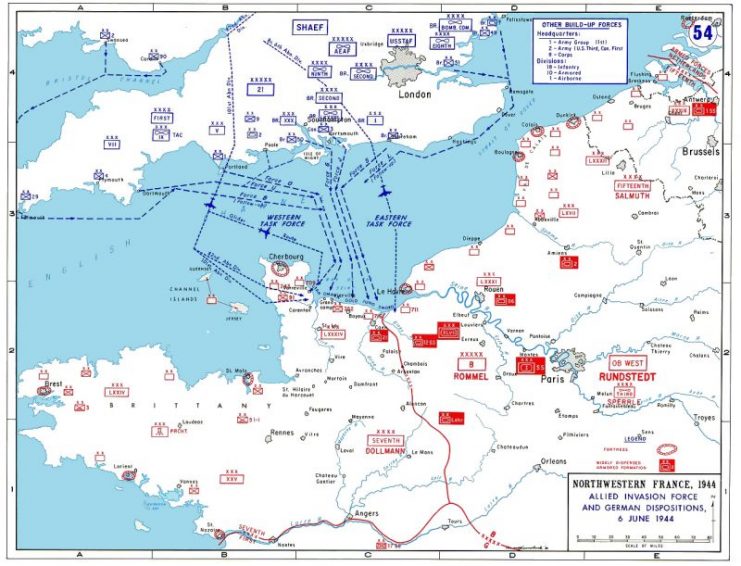

As the invasion force sailed across the Channel on the 6th of June, they were preceded and accompanied by the air forces.

The intense bombing of bridges, railways, and rolling stock, combined with sabotage by the French Resistance, mauled German lines of communication and crippled their ability to bring troops to the front. The work of the preceding weeks climaxed in a final round of attacks close to the landing beaches.

There were also air attacks against German defenses in the invasion area. By vigorously pounding the German positions, the RAF and USAAF softened them up before the troops landed.

Meanwhile, other pilots carried advance troops across the Channel. They towed gliders and carried parachutists, dropping paratroopers behind enemy lines. There they seized key objectives before the Germans could rally a response.

Critical to this operation were the fighter pilots. Luftwaffe interceptors were outnumbered and driven off by the Allies, keeping them from attacking the bombers. Fighters also held back German bombers from attacking the landing fleet and shot down German planes approaching the troops on the ground.

The Limits of Air Power

Beyond the first day and the forging of the initial beachheads, air power continued to be critical. Bombers attacked German communication lines. Fighters harassed troops in the field. This left the enemy anxious and defensive, unable to properly assemble a counter-attack thanks to broken bridges and fear of an air attack.

But while this period showed the potential of air power, it also showed its limits. RAF and USAAF claims for the amount of damage they did were clearly exaggerated, whether for political reasons or simply out of an over-exaggerated sense of their own power. Amid the fog of war, the belief in achievements outstripped reality.

The potential of air power was also limited by the doctrine followed by Harris and Spaatz. Both men believed that bombing was a war-winning tool on its own and that the best use of their air fleets was in strategic bombing campaigns.

This attitude pervaded both air forces. Air commanders resisted or even refused calls upon them to provide close support for ground troops through tactical bombing, instead focusing their resources on the strategic campaign. This was done despite the proven success of the Germans with tactical air strikes.

The one notable exception was an American, General Elwood R. “Pete” Quesada. Instead of a suspicion of close support tactics, Quesada showed great enthusiasm for exploring their potential, providing the support ground forces called for.

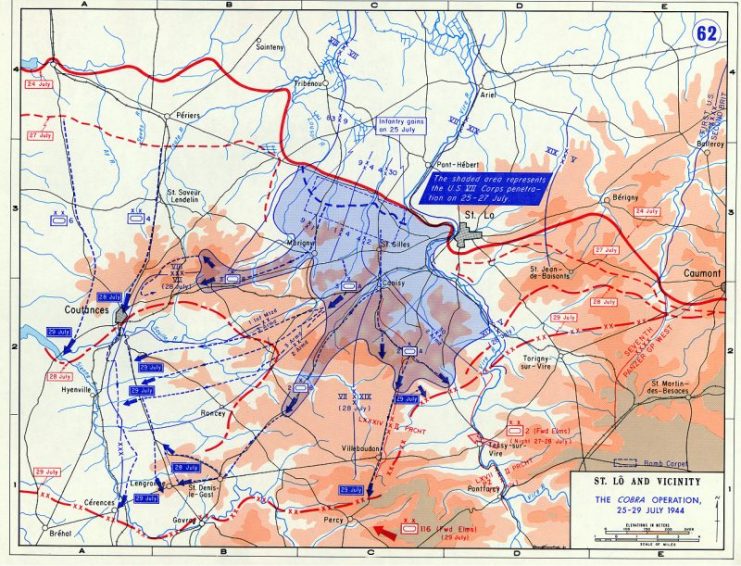

Cobra

After D-Day, the next significant use of focused air power came in late July with the launch of Operation Cobra. A focused American advance, this was preceded by the bombing of German positions across a narrow front. The aim was to leave the defenders too weak to offer significant opposition.

The bombing preparation for Cobra caused some problems. Some of the planes dropped their bombs short of the German lines, hitting Americans instead. This mistake, which may have been caused by drifting smoke, shook the Allied troops and undermined their faith in their airborne comrades.

Despite such errors, the Cobra bombing was a success. It left the target area of the German lines weakened. As the Americans advanced, again with air support, the enemy crumbled. American forces punched through German lines, creating a breakthrough that ended their containment of the Normandy coast.

The Falaise Gap

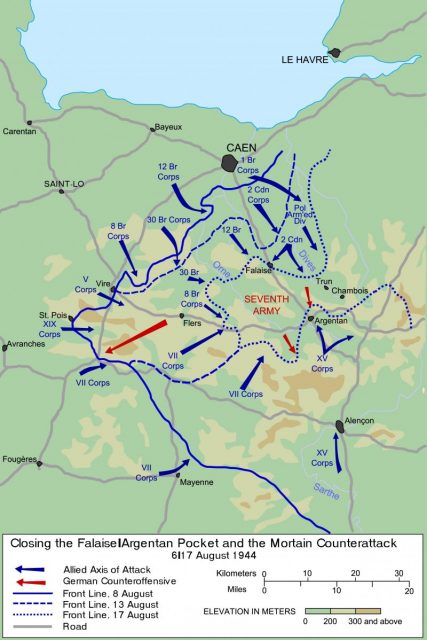

Cobra led directly to the last great battle of the Normandy campaign, the closing of the Falaise gap.

After striking south, American forces turned east, getting behind the German soldiers still trying to contain the Allies on the coast. Tens of thousands of Germans were surrounded on three sides by the Allies in a pocket of land west of the town of Falaise.

The Allies aimed to surround them by sending Canadian and Polish troops south to cut off the neck of the pocket and link up with the Americans.

Air power again came to the fore. As the Canadians and Poles advanced, they were supported by fighter-bombers attacking German positions. The Axis troops trying to flee through the gap also came under attack, pilots making the most of a target rich environment to hurt the Nazi war machine.

Again, there were mixed results. The Germans took heavy losses, but the Allies also suffered, as a lack of coordination between air and ground forces led to friendly fire incidents.

However, the gap was closed, and the final great act of the Normandy campaign was complete. The RAF and USAAF, which had played a prominent role throughout, turned their eyes east for the advance on Germany.