Alan Turing was a British mathematician and cryptanalyst who worked tirelessly with a team of codebreakers during the Second World War. Together, they cracked encrypted German communications to help the Allies. However, Turing’s own contributions stood out among the group, as he developed approaches of deciphering encryptions that proved invaluable to the outcome of the conflict.

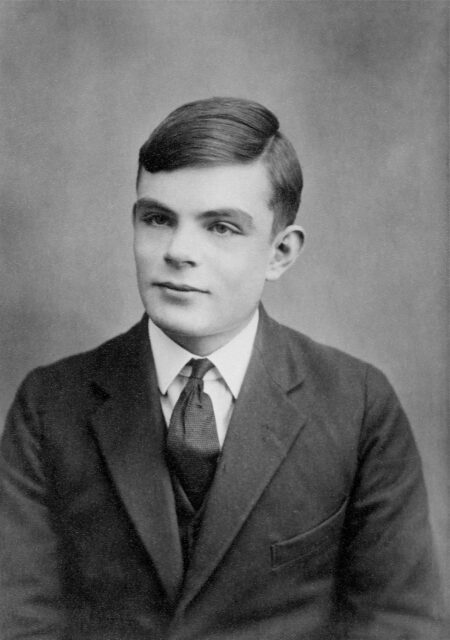

Alan Turing was a brilliant mind from an early age

Alan Turing was born in London in 1912, and showed intellectual promise from a young age. Between the ages of six and nine, he attended St. Michael’s Primary School, where the headmistress noted he was brilliant mind, saying she’d “had clever boys and hardworking boys, but Alan is a genius.”

Throughout his studies, Turing showed a natural inclination for mathematics and science. These interests were piqued further following his friendship with Christopher Morcom, who shared in this natural inclination. Morcom is said to have been Turing’s first love. When he died in 1930, it seems Turing channelled his grief into studying.

Turing attended King’s College, where he was awarded first-class honors in mathematics. He then attended Princeton, where he studied both mathematics and cryptology. When World War II broke out in 1939, he began a full-time position at Bletchley Park, in Buckinghamshire, which became the headquarters for Britain’s top codebreakers. There, they began to crack German military codes.

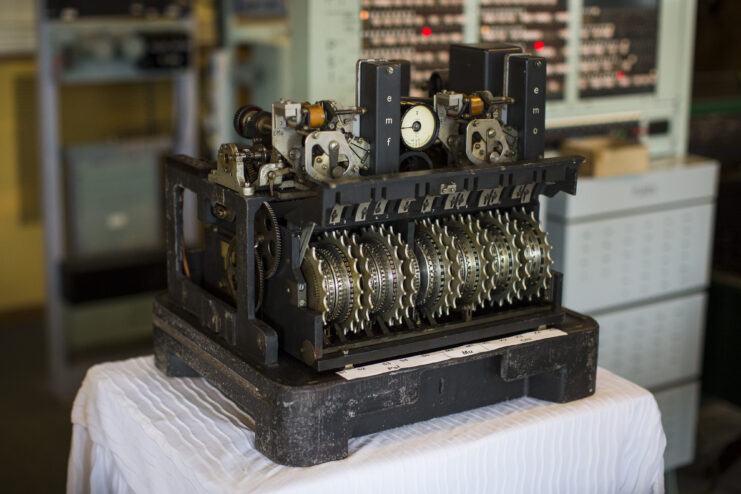

A Bombe named ‘Victory’

Throughout the war, the German military used a machine that encrypted messages. It was known as “Enigma,” and it used a typewriter-like keyboard to transmit messages through a series of rotating wheels and a plugboard, scrambling the output. It could only be deciphered using the correct settings, and allowed for encoding to occur in an incalculable number of ways.

Cracking the German Enigma seemed like an impossible feat, and the team at Bletchley Park were tasked with trying to do so. Polish mathematicians had already figured out how to read Enigma and shared this information with the British. The Germans, however, strengthened their security by changing their cipher system daily.

Alan Turing’s efforts to decode Enigma resulted in his inventing of the Bombe. Named “Victory,” it was an electromagnetic device that used logic to decipher the Germans’ messages. It didn’t decipher the messages directly, but, instead, drastically reduced the number of possible encryptions to a more manageable number.

By mid-1940, Luftwaffe signals were being decrypted and read at Bletchley Park. Deciphering the Enigma soon became faster. One example saw a message decoded, translated and read by the British Admiralty in less than 15 minutes. By 1943, Victory was helping decode a whopping 84,000 Enigma messages a month.

Alan Turing and the U-boat threat

Victory wasn’t the only contribution Alan Turing made to the war effort. One of the biggest threats to the Allied forces were the Germans’ U-boat “wolfpacks.” The Kriegsmarine had established its own, more complex, communications that Turing set his sights on deciphering.

He worked with the Hut 8 team at Bletchley Park, which was in charge of decrypting German naval communications. Using what he knew about Enigma, he developed a new technique called “Banburismus,” which inferred information about the Enigma machine using sequential conditional probability.

As a result, German naval messages were being read by British forces as early as 1941. This was invaluable to Allied convoys, who rerouted their trajectories based on the information. Prime Minister Winston Churchill once said, “The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.” Turing ensured the threat was minimized.

Going head-to-head with the Lorenz cipher

From 1942-onwards, the Germans introduced a new, more powerful cipher machine for correspondence between high-level commanders in Berlin and Commands across Europe. The Lorenz cipher was used by SZ40 and SZ42 machines. The British nicknamed the communications coming through, “Tunny.”

Turingery, developed by Turing, was a manual cryptanalysis technique that based its deciphering on the assumed wheel settings of the teleprinter rotor stream cipher machines. Breaking the Tunny messages provided detailed knowledge of German strategy and greatly affected the outcome of the war.

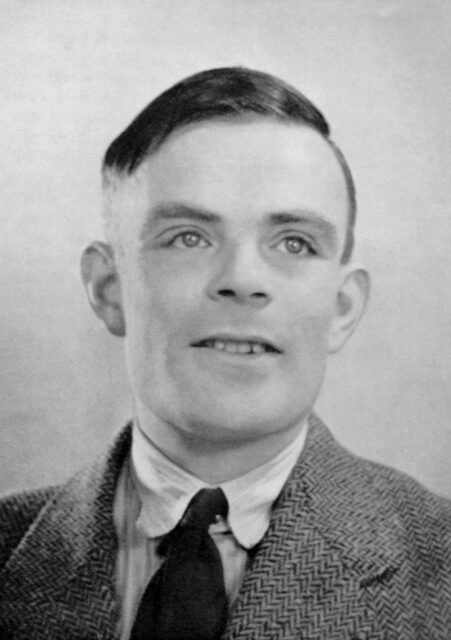

Alan Turing’s life after World War II was difficult

While Alan Turing didn’t work alone at Bletchley Park, his work in deciphering German encrypted correspondence was integral to the Allied war effort. Some historians estimate that the Enigma codebreaking and all subsequent deciphering done at Bletchley Park actually shortened the war by two-to-four years. This means a potential 14 to 21 million lives were saved as a result of the work done by Turing and the rest of the codebreaking team.

Following the close of the war in 1945, Turing was awarded an Order of the British Empire (OBE), despite his contributions being concealed from the public for decades. Prior to the the conflict, he’d been working on a hypothetical computing machine, known as the “universal Turing machine,” which he returned to after. He also worked with the National Physical Laboratory to develop a design for the Automatic Computing Engine, a forerunner to the modern computer.

Sadly, Turing’s contributions to mathematics, science and the war effort weren’t enough to save him from being arrested in 1952, on charges of homosexuality. Illegal in Britain at the time, he was convicted of “gross indecency.” Instead of being sent to prison, Turing accepted chemical castration, which took a toll on him. He was found dead by cyanide poisoning just two years later; he’d taken his own life.

More from us: Desmond Doss Was the Only Conscientious Objector to Receive the Medal of Honor in World War II

Turing’s story was kept secret until the 1970s, and it didn’t become more widely-known until the 1990s. In 2014, The Imitation Game, a film depicting a fictionalized version of Turing’s life and contributions to the war effort, was released.