Following the arrival of American troops in North Africa in late 1942, the Allies began pressing the Germans and Italians from two directions – the Americans coming from the west and the British from the east. The heart of the Axis forces was Tunisia, and it was towards here that the Anglo-American forces pushed. And so, in November 1942, the Allies made their first attempt to seize Tunisia.

A Mixed Force

The Allied forces coming out of the west were predominantly American, but there were others in the mix. A smaller group of British forces had joined with them in the Operation Torch landings. They were also now supported by those French forces that had chosen to switch sides rather than fight for the Axis-oriented Vichy government.

The Allies had initially kept the involvement of the British minimal, due to tensions between them and the French. But as they pushed into Tunisia, British commanders and troops were given a more prominent role. They had been fighting the Axis in the region since 1939, and so brought the benefit of experience the Americans had not yet gained.

Contrasting Commanders

The push into Tunisia, aimed at seizing the ports of Tunis and Bizerte, was headed by the British First Army under Lieutenant General Kenneth A. N. Anderson. He had served in the First World War but had no successful experience commanding at this level.

In contrast, the Axis forces were led by the German General Nehring, a battle-scarred veteran of some of the most intense fighting in North Africa.

The troops matched their commanders. The British forces involved had little combat experience, the Americans none. The Germans, on the other hand, had been fighting in the region for several years.

The Route of Advance

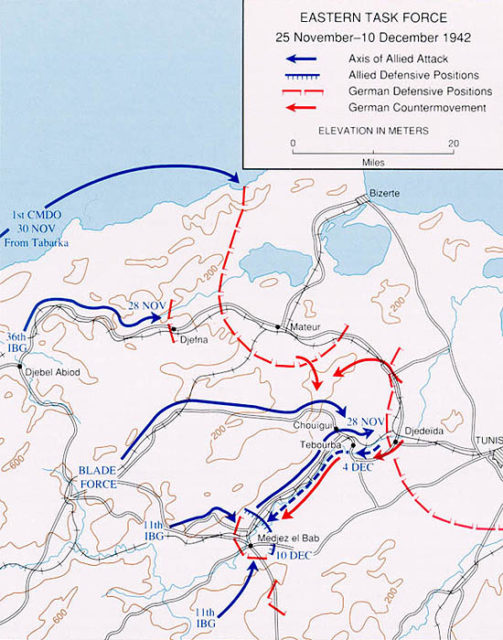

The geography of Tunisia pushed Anderson towards a specific strategy. Blade Force – a combination of his First Army and the American 1st Armored Division – would push between two areas of high ground and seize Chouisgui Pass, an important route connecting the two Axis bridgeheads at Bizerte and Tunis. They would then advance to seize those ports.

Heading In

The operation began on the 25th of November 1942. It got off to a promising start, with American armored forces brushing aside the Germans and Italians who had not yet had time to set up defensive positions. The Allies were soon into Chouigui Pass and seized an Axis airfield, destroying planes on the ground.

The problem for the Americans was that they lacked critical support troops, including artillery, engineers, and anti-tank guns. This would soon start to tell against them.

That night, both sides pulled back. This earned Nehring a lecture from Field Marshal Albrecht Kesselring, who believed that the Allies would advance slowly and cautiously.

The Fight Heats Up

Under pressure from Kesselring, Nehring sent a force of tanks to probe the Allies and see how they held. They engaged one American tank company, only to be attacked in the flank by another. In the first clash of the war between American and German tanks, both sides took significant losses before the Germans withdrew.

Advancing put the Allies at a serious disadvantage. They were now a long way from their airbases. By the time their air support reached them, the planes had already used up nearly half their fuel and so could not stick around for long. The Germans, on the other hand, had airbases nearby. They were able to spend far longer above the battlefields, strafing and divebombing Allied troops. Even when Allied planes got into action, they sometimes got targets confused and attacked their own side.

The soldiers on the ground suffered from a steady stream of air attacks.

The Southern Flank

Further south, British and American forces attacked the town of Medjez el Bab. Their assault on the first day was driven back by the Germans, who Nehring then withdrew overnight. On the 26th, the Allies marched into the town unopposed, to find that its bridge had been partially demolished.

These troops then turned north. On the 29th, they tried to seize the German airbase at Djedeida. The Germans endured a brief artillery barrage before mustering an effective defense with artillery, machine guns, and antitank guns, driving the Allies back.

The Northern Flank

The advance in the north started on the 28th, with the British 36th Brigade advancing along the road towards Bizerte. Approaching a pair of hills, they looked for signs of the enemy but couldn’t see them, so continued their march.

It was a terrible mistake. German forces were hiding in the brush on the hillsides. As the British marched between the hills, the Germans ambushed them, devastating the column. The British survivors eventually retreated, abandoning the push towards Bizerte.

Outflanking the Flank

A group of British commandos and American infantrymen were transported around the coast to get behind Axis lines in the north. They were to take control of the road towards Bizerte and hold it open for the British advance.

By the time they landed on the 1st of December, that advance had already failed, but they were unaware of this. They held the road for three days. By then, they were low on supplies, under attack from German tanks and infantry, and could see that the other forces weren’t coming. The survivors set off west across hills and mountains, reaching friendly lines five days after they had arrived in enemy territory.

The End, For Now

With the offensive stalled on all fronts, Anderson called a halt on the 30th of November. He had concluded that, until they dealt with German air superiority, there was no chance for the Allies to succeed.

An Axis attack in early December drove the Allies back. This was followed by a failed Allied attempt to seize and hold a key hill over Christmas, which ended in bloody defeat. By the end of the year, the first battle for Tunisia was over, and the Axis had won.

But the war in that region was still far from done. The Allies would return to storm Tunisia again.