Everyone has a story about how they came to join the military. Some do it for the opportunity it presents. Others do it for patriotism. Some are even forced into it.

Florence Ebersole Smith enlisted for one reason: revenge.

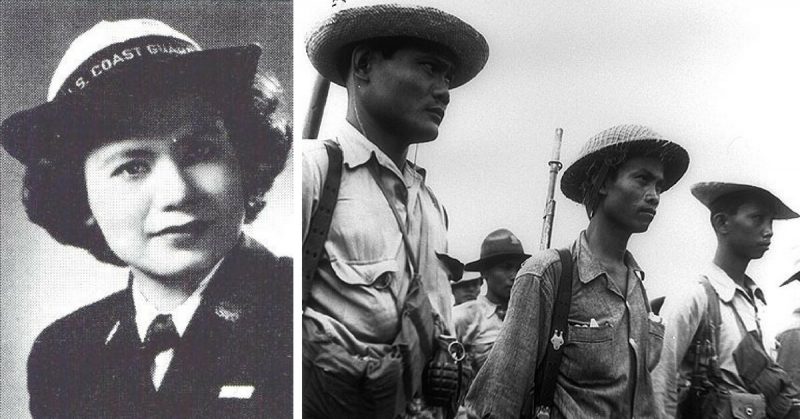

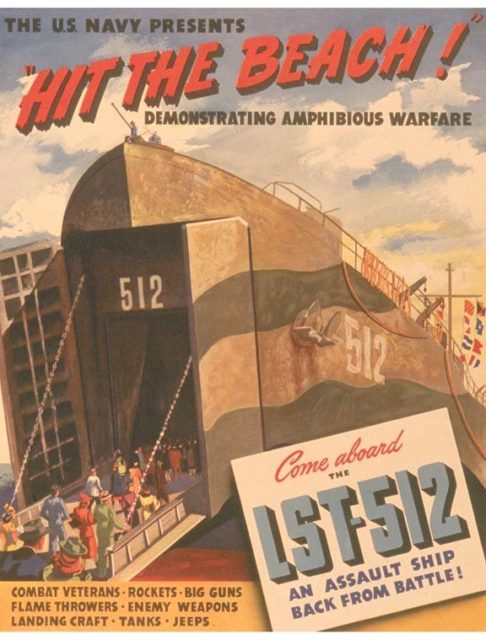

Smith enlisted in the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve, better known as SPARs (Semper Paratus – Always Ready) on July 13th, 1945, aboard LST-512. She attended basic training at MBT (Manhattan Beach Training Station), and in her second week there was asked why she enlisted.

She calmly replied: “to avenge the death of my husband.” Enlisting in the SPARs, however, was only the final chapter, in what was an incredible career during the Second World War.

Florence Ebersole was born in Santiago, Isabela province, in the Philippines, in 1915. Her mother was a native Filipino woman, and her father was a US Army veteran of the Spanish-American war.

After graduating from high school, Florence began working with US Army intelligence in Manila, the capital of the Philippines. Here she met her 1st husband, Chief Electricians Mate Charles Edward Smith, who also worked as a crewman on a PT Boat. They were married on August 19, 1941, only months before the United States and Japan were at war.

When the war was declared on December 8, 1941, Chief Smith reported for duty on board his PT Boat. They joined the fleet to defend the islands from the Japanese who attacked the same day. Their invasion of the Philippines had begun.

On December 22, 1941, the main force attacked, quickly smashing through the ill-equipped and untrained American troops on the island. Florence Ebersole Smith was in Manila at the time, with two armies advancing from either side.

On the 25th, all Military personnel were ordered to evacuate, and the whole of the Army Intelligence office packed up and left. They knew if they were captured they would likely be subjected to harsh interrogations, and their information was too valuable to lose.

Florence, however, stayed. She had to care for her 16-year-old sister, who had no prospects and no protection.

By January the Japanese had taken Manila and began to round up all Americans living there. The Philippines had been a U.S. territory from 1898 and Americans had been living on the islands since then.

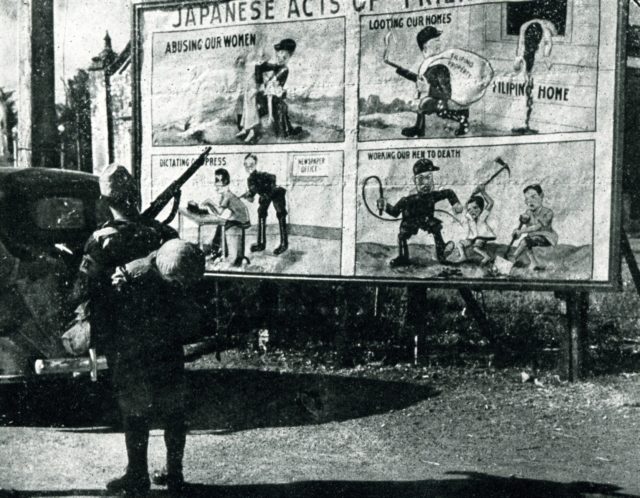

They posed a potential threat to the Japanese occupiers, who did not want any possible organized resistance. These Americans were placed in internment camps, subjected to cruel treatment, and forced to work for their occupiers.

Florence Smith knew she could be of no use inside one of these camps, so she hid her American citizenship. When asked, she explained she was a Filipino native, which was at least half true, as her mother was Filipino. Thanks to this bluff, the Japanese did not immediately intern her, but rather offered her a job.

They knew she had done clerical work for the US Government, so she was offered the job of writing names on fuel ration tickets. Little did the Japanese realize they had just given a potentially powerful weapon to a woman with connections to US Army intelligence!

Shortly after she began this new career, members of the Filipino resistance contacted her. They knew she had no love for the Japanese as her husband had died fighting them in February 1942. Her entire world was collapsing around her. They also knew she was familiar with clandestine work, having been around the intelligence community for most of her adult life.

They offered her a simple task: forge ration documents. Smith was one of the last people in a long bureaucratic chain for fuel rations, and she could write in whatever name she wanted on the ration cards.

Guerrilla members used false names, and Smith would write a ration ticket for them and smuggle these falsified tickets out. A courier would pick them up, and distribute them to the resistance members.

The Filipino resistance proved an almost constant nuisance for their Japanese occupiers. From propaganda campaigns to intelligence gathering, to even armed resistance and sabotage, the guerrillas harassed the enemy force at every opportunity.

They assisted in the recovery of prisoners of war, and the removal of minefields and hunted out Japanese spies in the Philippine populace. Florence Ebersole Smith never took up arms with them, although other Filipino women did.

Her ability to supply them with fuel, food, and clothing rations were a vital asset to the local resistance groups on Luzon.

Smith also aided the American and British internees at the Santo Tomas internment camp, where most enemy Aliens were held prisoner by the Japanese. This was the former University of Santo Tomas, a massive walled complex which the Japanese took over.

Receiving a note from her former boss at the Intelligence Office she began smuggling what little food and medicine she could spare to the American prisoners of war at the Bilibid Prison. However, her actions had begun to be noticed.

She had been forced out of her home in Manila as it was needed for Japanese officers. She moved to Tondo, by Manila Bay. She had also stopped working at the Fuel Union.

Finally, a pair of Japanese soldiers apprehended her. They charged her with collaboration with the resistance and took her to a local military station. She was forced to live at the station for around a week, with no contact with the outside world.

This was where she was first interrogated by the Japanese. Military officers used electric shocks if they did not like her answers, but Smith never gave away any information.

She was taken to the Bilibid prison, a major POW camp, with 1200 personnel interred there. She was subjected to even more interrogations, by Japanese intelligence officers.

From Bilibid she was moved again, this time to the Mandaluyong Womens’ Prison which was liberated as the US Military arrived on February 10, 1945.

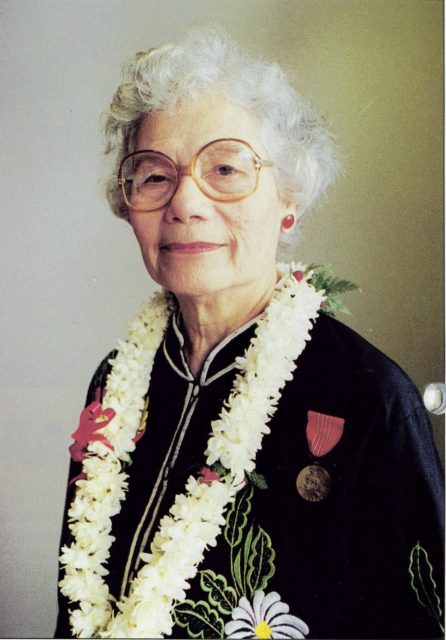

Florence Ebersole Smith Finch (Finch from her 2nd marriage) in 1995 at 80 years old. She has always been very proud of her service to her fellow Americans and Filipinos during the war.

Like all American citizens living in the Philippines, Florence was repatriated back to the United States. She eventually made her way to New York City, and it was while living there she decided to enlist in the US Coast Guard Women’s Reserve.

Florence Ebersole Smith Finch served her nation in some of the worst possible conditions a civilian can endure during a war. Despite the high risk to her own safety, she regularly smuggled supplies, forged documents, and food to Filipino resistance fighters, American POWs, and civilian internees.

She was awarded the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Ribbon, the first woman to receive the medal. For her bravery and willingness to help others, she was given the Medal of Freedom in November 1947.

This is the highest award a civilian, living outside the United States, can receive during war time.