Deborah Lipstadt is a historian whose recent book, History on Trial, has been made into the movie, Denial. Ask her whether Holocaust denial is still something that happens nowadays and she’ll point you to YouTube.

“Of course the thumbs down and the comments on the trailer were pure anti-semitism,” Lipstadt said.

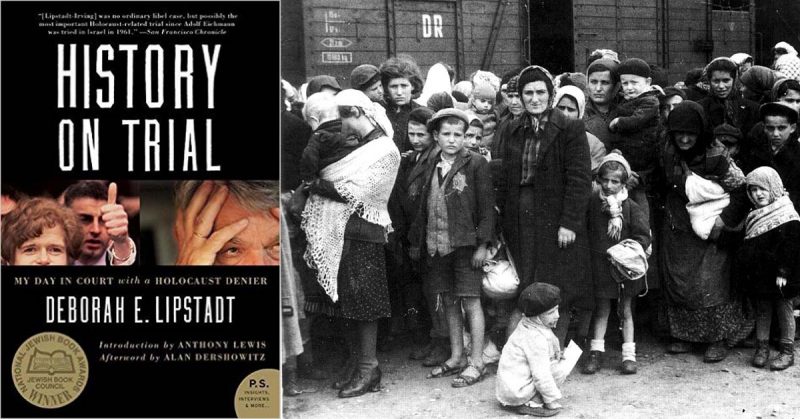

The book was recently re-released with the same title as the movie. Both tell a true story about the aftermath of Lipstadt’s 1993 book, Denying the Holocaust. David Irving, one of the people discussed in her book, sued her for libel in the UK. Due to the burden of proof in the British legal system, Lipstadt and her legal team essentially had to prove that the Holocaust happened so that they could prove her comments were not defamatory but rather, it was Irving’s interpretations that were incorrect. They were successful in doing just that. When she first looked at Holocaust denial, she assumed it was a short divergence from the rest of her career. Now, it is the work for which she is best known.

It’s been a long time from the end of World War II to the age of YouTube comments, and the form that Holocaust denial – claiming that all or part of the Holocaust is an elaborate hoax or conspiracy – has changed a lot in the interim.

During the mid-70s, the deniers did what many conspiracy theorists and extremist groups do. They held on to their beliefs, but they became more academic in presenting those beliefs. As Lipstadt explains, “They began to publish books with footnotes. They began to hold conferences. They began to show up on television where they were often given a voice. But instead of looking like neo-Nazis, dressed in stormtrooper uniforms, they began to talk in a very measured way about how the documents showed that the Holocaust was impossible.”

Lipstadt explains the success of this shift to the rise of deconstructionism. In her definition, this is the concept “that you can look at a document and interpret it in any way you wish.” There are benefits to the idea since it makes people open to looking at history from more than one side. However, it gave deniers a way to frame their beliefs in a way that academics took as a legitimate opinion.

“But if I said to you that I believe that the Earth is flat or I believe the Civil War never happened, I could say ‘that’s my opinion’ and you would end the conversation very quickly,” Lipstadt explains. “That’s not opinion, that’s a lie.”

When the Internet arrived, it provided a platform for people who believed the deniers to find others who believed the same things. It’s not just the Holocaust deniers that have found this to be true, Time reported.

Lipstadt sees this as an age where people with outlandish ideas are able to find an audience that is willing to listen and believe them. “If some people take away from this movie the notion that there’s a difference between facts, opinions, and lies, I will be very satisfied.”