By the time the D-Day invasion was launched in June 1944, the south of England had spent months filled with soldiers preparing for war.

The arrival of hundreds of thousands of Americans and Canadians left many Britons feeling as if their own country had been occupied, even if it was by a largely friendly force. It was a strange period, both exciting and unsettling.

An Army in Waiting

Over the winter of 1943-4, troops assembled along the British south coast. These were the men who would liberate Europe from Nazi occupation, an international force drawn from a dozen countries, ranging from entire British armies down to a single Luxembourgian artillery unit.

By far the largest group were the Americans, who would commit 130,000 men on D-Day and a million more over the three months that followed.

Some of these men, the Canadians in particular, had been there waiting for years. But now the preparations intensified and the occupying forces grew.

The Cages

On the 10th of March, 1944, strict controls were brought in to limit movement, mail, and other communications through and from the south of England. This didn’t just restrict soldiers, for whom all leave was canceled from the 6th of April. Civilians also found their movements severely limited.

On the 26th of April, the soldiers were sealed up in their “cages,” as their training camps were known. Both the inner and outer perimeters of the armed areas were closely guarded.

Civilians within ten miles of the south coast found themselves living in a prohibited zone where daily life was governed not by the police but by armed foreigners. The populations of entire villages were turfed out to create training areas, the inhabitants losing their family homes forever.

Staying Entertained

Inside their camps, over two million soldiers waited, many of them far from home. In the early days, they could take leave or be granted brief passes to go beyond the wire. Servicemen from across half the world were scattered over the southern counties, the officers heading to the bright lights of London while most of their men went to local pubs.

Once the lockdown came, it was harder to get out. The men lived in tents or Nissen huts inside rings of barbed wire. They gambled, read cheap paperback books, and chatted in their barracks blocks.

The tension of knowing that they would soon have to fight was exacerbated by confinement, but resentment soon gave way to resignation at being cut off from the world. This was the price of heroism.

Travel

Despite the travel restrictions, the roads in the occupied zone became crowded with traffic. Large numbers of slow-moving war machines were being transported to training fields and departure points, accompanied by fleets of cargo trucks, to the frustration of those stuck behind them on the roads.

The military took over control of traffic, not just directing cars but overseeing travel by public transport, watching out for spies and saboteurs. American military police, known as Snowdrops because of their white helmets, became a familiar sight.

Training

The troops weren’t sitting idle while they waited to go to war. They were about to take part in the greatest amphibious operation in history, and they had to prepare for that.

Whole swathes of countryside were taken over for training. Soldiers practiced house-to-house combat through requisitioned homes.

On the coast, they experienced the reality of traveling by landing craft, including dismounting into the water and making their way to shore, sometimes under fire as part of the exercise.

Local Relations

Signs outside the camps ordered civilians not to talk to the troops, and for the most part, they kept their distance. It was easier to get on with life while pretending that nothing was happening than it was to engage with the surreal situation.

Of course, some people were excited to meet the new arrivals. The presence of thousands of fit young men, far from home and looking for company, had an undeniable appeal to young women.

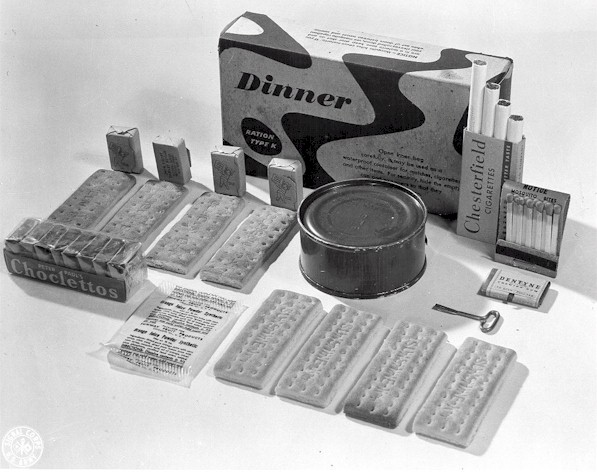

The Americans in particular were not just exotic heroes in smartly presented uniforms, they were also the bearers of incredible luxuries. Some of these were bought specially, but most came in their rations.

The American soldier received a ration pack substantially larger than that of his British comrade in arms, a pack that included candy and cigarettes. They were even supplied with condoms to prevent STDs crippling the army.

In a country that had been living with strict rationing since the war began, where finding any extra food was a struggle, spare American rations were a luxury, never mind the chocolate and cigarettes.

While their wealth could win the Americans favors, it also created resentment. A secret government survey in 1943 found that the Americans were less popular among the British public than the Italians who, until recently, had been their enemies.

British soldiers had particular cause for resentment. They received less pay and fewer provisions than their comrades from across the Atlantic. The brash confidence of the Americans created constant tension with the more understated Brits. That tension, which had caused bar brawls among the Allies in North Africa, had to be constantly monitored.

Departure

On the 5th of June, after a false start the previous day, the soldiers were loaded into their transports. Under cover of night, they set off across the Channel, heading for Normandy, a vast aerial armada accompanying them overhead.

That morning, civilians on the coast woke to find formerly crowded harbors empty. They would still be living with foreign forces for months to come, but at least now some of the pressure had eased off, some of the secrecy and security could be relaxed, and the roads could start going back to normal.

Read another story from us: D-Day Up Close -Dozens of Photos Show the Allies Normandy Invasion

The occupation was over. And across the sea, the work of liberation had begun.