Towards the end of 1943, Allied forces were struggling to fight their way up Italy in the face of stern resistance from German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring. Central Italian scenery gave an advantage to the defenders, an advantage of which Kesselring was making great use. And so the allies found themselves stalled across the peninsula, most famously at Monte Casino.

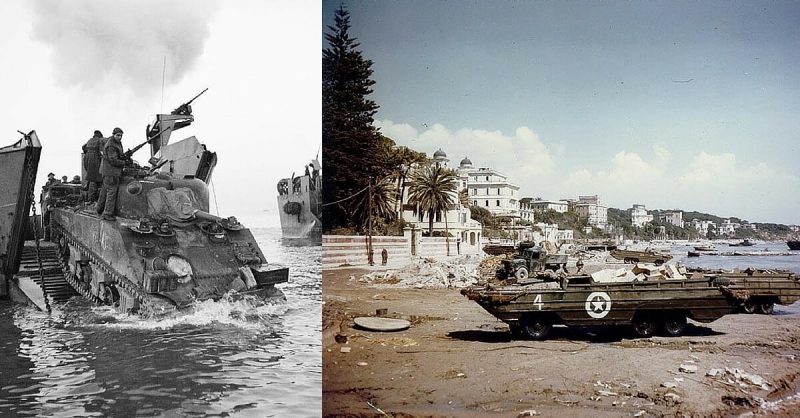

A plan named Operation Shingle was devised to break the deadlock. An amphibious assault by American and British troops would land at Anzio and Nettuno on the west coast. Using the element of surprise, they would provide the Allies with a strategic advantage, allowing them to break past Monte Casino and reach Rome.

The operation began on 22 January 1944, with landings that were almost entirely unopposed. The chance had come for a ground-breaking victory. Yet the Anzio landings would ultimately fail to live up to their promise.

1. Geography

The central challenge of the operation, and the reason why the Germans were not defending the area more strongly, was terrain. The area consisted largely of reclaimed marshes, terrain which armies had historically avoided due to difficult travel and the dangers of disease.

Overlooked by mountains in nearly every direction, this was a potential death trap. If the army did not break out then they would be surrounded in the marshland, at the mercy of enemies holding the high ground. Only a swift victory against low opposition could avoid such a situation.

2. Communications and Confidence

For such an operation to succeed, it needed clear objectives and a commander who had confidence in the plan. Unfortunately for the troops at Anzio, they had neither.

Senior military and political figures had different views on what the operation was meant to do. The Americans regarded it as a risky way of distracting the Germans from Monte Casino. The British, whose Prime Minister Winston Churchill had kept the plan alive, saw it as a chance to outflank the enemy and take Rome. These differences had been papered over rather than resolved during the planning stages, leaving the objective of the landings ambiguous.

This ambiguity was allowed to fester in the orders given by Lieutenant General Clark, the US Fifth Army commander, to Major General Lucas, the man leading the expedition. Lucas had been ordered to form a beachhead, advance and “be prepared to advance on Rome”, but there was no urgency in the orders, no emphasis on a speedy advance, no clarity on when and how the advance on Rome should come.

3. Not Enough Men

One of the reasons for the lack of enthusiasm for the operation, and why Lucas’s orders gave him so much wiggle room, was the number of soldiers committed to the operation. Most of the military staff involved believed that not enough troops had been supplied to ensure the desired breakout. A dangerous mission was being made foolhardy through a half-hearted effort.

4. Losing the Element of Surprise

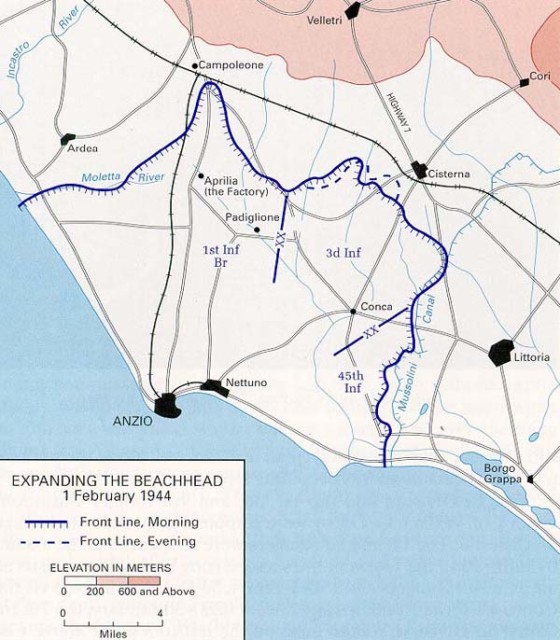

Lucas was a cautious commander and made the most of the space his orders gave him. Having secured a beachhead and advanced a few miles inland, he settled in to better defend that beachhead. There was no strong advance to break out of the coastal trap. An offer of guides through the mountains from the Italian resistance was rejected.

Historian John Keegan has argued that Lucas chose the worst of all options. An immediate advance on Rome on 22 January, without reorganising after the landing, would probably have led to failure. But Lucas delayed far longer than was needed, losing the element of surprise and ensuring he would not break through.

5. Kesselring Counters

Kesselring had no way of knowing that the landings were coming, or where they would be. But he had prepared for the likelihood of such a manoeuvre. Should such a landing take place, fast-moving German troops were to leave their divisions and head for the landing site. There they would contain the invaders, giving the rest of the army time to plan and react.

This operation, unlike Lucas’s, worked as planned. Kesselring knew that if the allies advanced on 23 or 24 January he would not be ready to hold them. But while Lucas dug in, Kesselring brought up troops. Within three days of the landing, the Allied troops were surrounded by three Panzer divisions, who proceeded to bombard them from the high ground.

6. Stalemate and Stale Water

A month of bitter but indecisive fighting followed, with each side making attacks and counter-attacks to little effect. Shells rained down on the Allied beachhead in the coastal lands.

To make matters worse, the Germans stopped the pumps that kept the marsh flats drained. As salt water started reoccupying the land, soldiers found themselves damp, cold and vulnerable to disease.

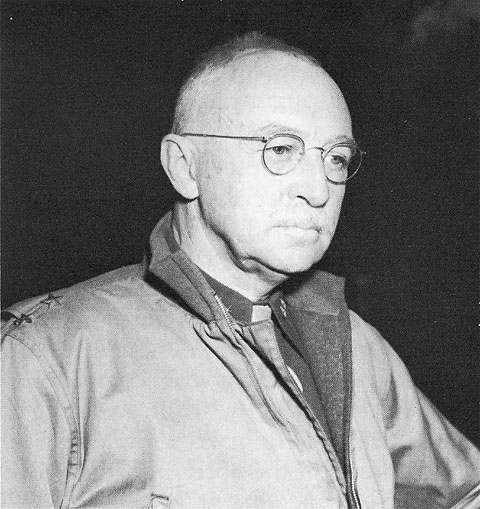

Lucas had lost any enthusiasm for the operation he ever had. After an inspection by his superiors, he wrote in his diary “there is no military reason for Shingle.” His failure to advance, and the lack of commitment shown by him and his staff, led the allies to make a change in command. On 22 February he was replaced by Major General Truscott, who had been assigned as one of his deputies a week before.

7. Focus on Rome

Three more months of stalemate followed. Finally, on 23 May, Truscott launched an attack that broke through the German lines. Over two days of intense fighting, the British and Americans broke out of their encirclement. Truscott expected to continue advancing north-east, to cut off German troops retreating from the wider allied advance.

But on the afternoon of 25 May, he received new orders from the American high command. He was to turn north-west and seize Rome. Dumbfounded at the wasted opportunity, Truscott obeyed the orders, and his forces turned their line of attack.

Rome was soon taken, the Germans abandoning their former defensive line. But the delay in a breakthrough at Anzio, and the decision to focus on Rome instead of cutting off the enemy’s retreat, meant that an opportunity for decisive success had been lost.