27th January 2020 marked the 75th Anniversary of the liberation of the mass extermination camp at Auschwitz in Poland.

World leaders gathered to commemorate this event, but for some of the first inmates of the camp, this was too difficult to watch.

One such survivor is Canadian resident, Edith Friedman Grosman. This lively 95-year-old, along with her sister, was on the first transport train to Auschwitz.

In an interview with the Washington Post, she said that she was unsure if she would watch the ceremony as it may simply be too much. She has been back to visit the camp on four occasions and feels this is enough.

Mrs. Friedman Grosman was born and raised in Hummené, a village in Slovakia. She lived with her parents and her sister Lea.

In 1940 Slovakia partnered with the Axis nations, and with that came the start of the persecution of the Jewish people.

Mr. Friedman had to sell the glass-cutting business that he owned to a Christian, and his daughters were forced to leave the public high school that they attended.

Shortly after, they were told that all the unmarried Jewish women over the age of 15 were to report to the school gymnasium.

The message they received was that they had to register and fullfil their patriotic duty to the war effort by working in a shoe factory for three months.

When they all arrived, they were strip-searched and loaded into trucks. The girls were mostly teenagers with a few in their twenties and a couple of mothers that took the place of their daughters.

Within a few short days, Edith and Lea Grosman were loaded onto a train, and on the 27th March 1942, they arrived at the infamous camp.

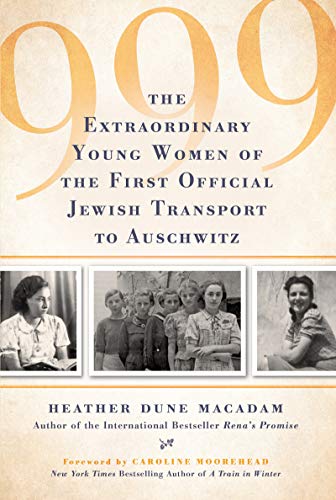

There is no record as to why just the girls were taken and who ordered this transport but historian, Heather Dune Macadam, who has extensively researched and documented these transports, believes that the Slovak Government in conjunction with Himmler were responsible.

Macadam found that Himmler had ordered that 999 German female prisoners were to be transferred from Ravensbruck prison to Auschwitz to serve as guards for the 999 Slovak Jewish girls that were supposed to arrive on the train. Authorities miscounted, and only 997 girls arrived on the train.

Initially, Auschwitz was a prison for Polish prisoners, irrespective of ethnicity.

It then started taking in Soviet prisoners-of-war, and by 1942 the Nazis had begun gathering up the Jewish people. However, they had not yet started their mass extermination.

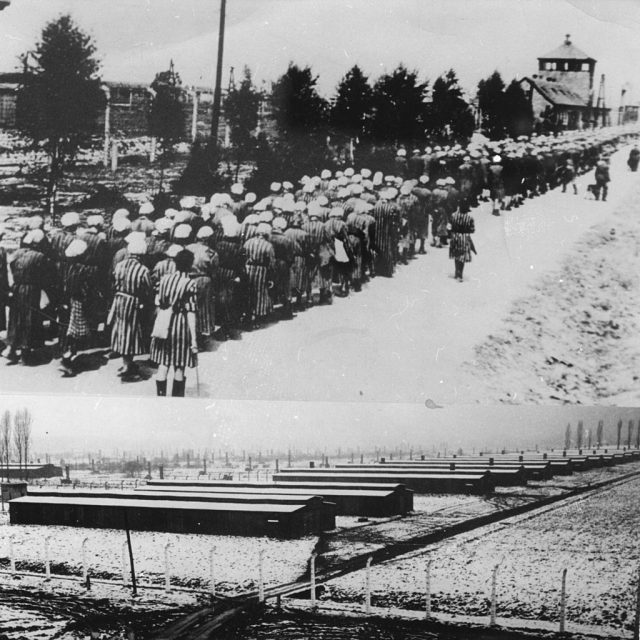

The girls found that they were not there to make shoes, but to build the camp that would be used to murder thousands of people deemed undesirable by the Nazi authorities.

For the next year, the girls undertook the back-breaking task of breaking down the existing buildings and building the barracks needed to house those unfortunate enough to be sent to the camp.

The clothing supplied was the blood-soaked uniforms collected from dead Soviet soldiers, and their shoes were thin planks of wood tied onto their feet with thin strips of cloth.

In that first year, the death toll amongst the girls was horrendous. Almost all of them died from cold, starvation, brutal treatment, medical experiments, disease, and suicide.

Mrs. Friedman Grosman remembers her sister, Lea, lying emaciated from the brutal regime and typhus amongst the filth and the rats.

As she was so ill, she was exterminated in a gas chamber. More than 77 years later, Mrs. Friedman Grosman still carries the scars of her grief.

As the Jewish prisoners began to flood into Auschwitz, those original inhabitants were given the so-called easy jobs.

Tasks such as typing in the offices, sorting through the confiscated luggage and clothing, or the gruesome task of moving the bodies from the gas chambers to the graves.

These jobs came with benefits such as extra rations. Still, it also came with the horrors of watching friends and family marched into the gas chambers.

The Soviet forces arrived to liberate Auschwitz on the 27th January 1945, but those girls that had survived since the beginning were not there to see the gates opened.

They had been force-marched out through the thick snow to other concentration camps in Germany.

Mrs. Friedman Grosman was marched to Ravensbruck, and then when this became overcrowded, she was moved on to Retzow.

Mrs. Friedman Grosman recalls that at Retzow, it became clear that Germany was losing the war. When the guards dived for cover during bombing raids, the inmates raided the kitchens for food.

When spring came, she, along with others, was once again force-marched to another camp. Along the way, she and ten other girls fell behind, and as they had not been noticed by the guards, they hid in a small shelter. The next morning, they found they had hidden in an apiary.

Eight long weeks later, Mrs. Friedman Grosman found her way back to her home village of Hummené. There to her astonishment, she discovered her parents had survived as had a young neighbor, Ladislav Grosman.

Edith spent the next three years in a Swiss sanatorium suffering from tuberculosis. When she was cleared of the disease, she and Ladislav were married.

The couple settled in Prague, and she bore one son. She returned to school and earned a degree in biology. Her husband pursued a successful career as a writer.

In the 1960s, the family moved to Israel, and in 1981, with the death of her husband, she joined her son in Toronto, Canada.

Many survivors of the Holocaust, especially women, are very reluctant to talk about their experiences. Because of this, the significance of this first transport to Auschwitz has mostly been forgotten.

Many female survivors struggled to fall pregnant due to their brutal treatment, and many survivors viewed anyone with a low number tattooed on their arm with deep suspicion.

It was felt that if you survived with a low number, you had to have done something unforgivable to have come through alive.

Mrs. Friedman Grosman’s number was 1970.

With the steady growth of the women’s movements around the world, interest in the first transport was revived.

The Shoah Foundation tracked down 22 women that survived from that first transport and of the 22 Macadam interviewed 20. Of those 20, only six are still alive.

Edit Friedman Grosman is well-loved in Slovakia today, and she often returns to talk about her life during the Holocaust.

She does have a message for the rest of the world. She implores people not to hate because hate breeds criminality, and hate brings death. She should know as she lived through such hate, criminality, and death.

Survivor of Massacre at Lidice Passes Away Aged 97, Now 1 Left Alive

Mrs. Friedman Grosman was pleased to see that there would be a memorial on the Anniversary but said that it needs to be repeated on the 100th or 125th anniversaries, so the world does not forget.