Who’s up for some pancakes? How about exploding pancakes?

In the midst of WWII technological acceleration, scientists on both sides were constantly engaged in figuring out how to use chemistry to their advantage. Different breeds of explosives were developed, each outmatching the destructive potential of their predecessors. In one such innovative attempt, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) developed an explosive powder that mimicked baking flour.

It was codenamed “Aunt Jemima” and was used rather extensively among Chinese guerrilla fighters who were battling the occupying Japanese forces. The name came from the popular brand of American pancake flour dating back to the end of the 19th century.

The OSS was the wartime predecessor of the CIA, engaged in providing material, strategic, and tactical support to various resistance groups who were fighting the Axis powers all around the world. The Chinese guerrilla’s, who were determined to kick out the Japanese invaders from their homeland, were happy to receive such help, for without the Allied support their efforts would be far less fruitful.

This was how an American chemist and physicist of Ukrainian descent, George Bogdan Kistiakowsky, managed to use his patent of explosive flour to help the insurgents. During WWII he was the technical director of the Explosives Research Laboratory (ERL), overseeing the development of cutting-edge explosives such as RDX and HMX. The later would be used in the explosive flour experiment, for HMX proved to be far less sensitive to premature explosion, which wasn’t the case with, let’s say, nitroglycerin.

The HMX mixture was combined with regular flour in order to produce explosives suitable for sabotage missions and diversions, while looking (and tasting) rather innocent. What came as the biggest oddity of this mixture was that it was actually edible, apart from being a very efficient explosive. The edible part was primarily made possible so that smugglers could demonstrate the flour to any doubting customs officer in occupied China.

It was easy to smuggle and easy to prepare, making it the perfect choice for under-trained guerrilla fighters who were not too savvy with explosives. As it was mentioned, the mixture was highly resilient to premature explosion which made it safer, as other more sensitive explosives would often do more damage to their users then the enemy when accidentally detonated. It wasn’t recommended, of course, but in wartime food is always scarce, and even though it tasted kind of gritty, cases were documented where the flour was actually used to feed the resistance fighters once there was nothing else to eat.

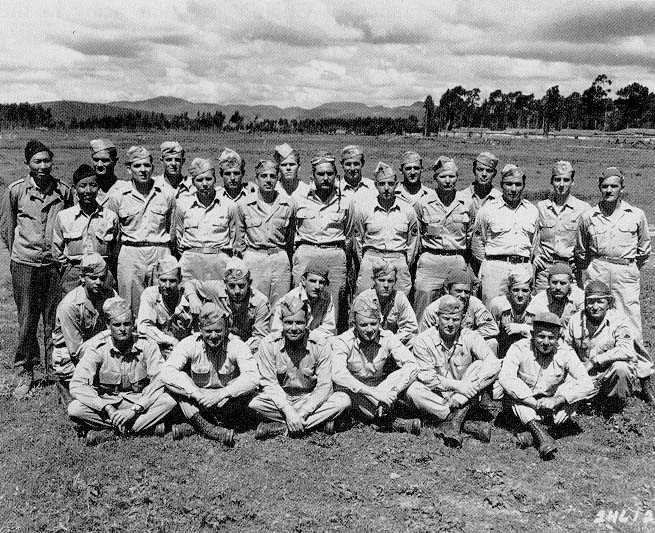

A veteran of the campaign, Frank Gleason, who served as an advisor and demolition expert in China, recalled his experience in a post-war interview:

“In China we made muffins from the stuff. I wanted to show Major Miles how you could bake Aunt Jemima into muffins, put a blasting cap into it, and blow something up. It looks like regular flour, but if you look carefully at a little piece, you’d see it was gritty, unlike flour. It could make bread, so I told this Chinese cook at Happy Valley to make some muffins out of the explosive flour. I said, “Do not eat those muffins! They are poison. Do not eat them!” You should have seen them when they came out of the oven. They were gorgeous. The cook thought to himself, “Those damn Americans just want those muffins for themselves!” He violated what I told him and he ate one. He almost died.’ ”

The mixture was further refined during the course of the war in order to reduce its toxicity. Even though it was still deemed rather unpleasant, at least it wasn’t causing nausea and vomiting upon consumption any more.

The uneaten pancakes, muffins and dough were often used as explosive devices. In China more than 15 tons of this unusual explosive was used in various successful missions. The origin of the mixture was never discovered by the Japanese, who never once thought that Aunt Jemima was entering the country disguised as cooking flour.