War History Online presents this Guest Article by McKay Smith

In the summer of 1944, Clem Dowler went from serving in the U.S. Army Air Corps to fighting alongside the Office of Strategic Services, one of World War II’s most elite intelligence units and predecessor to today’s CIA.

Clem Dowler’s Extraordinary Journey Fighting Alongside the Office of Strategic Services in Occupied France:

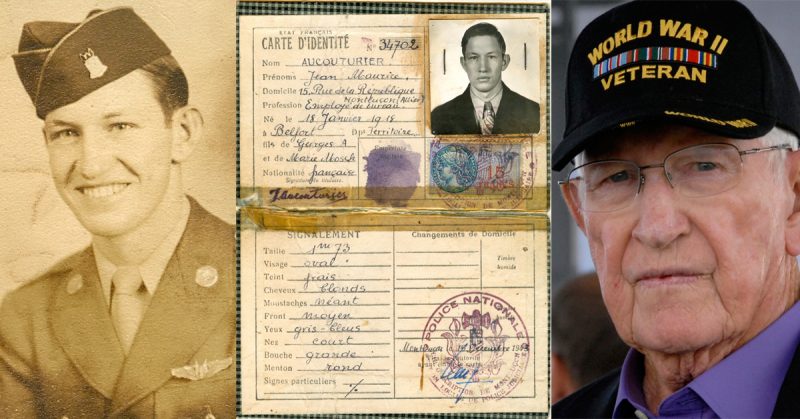

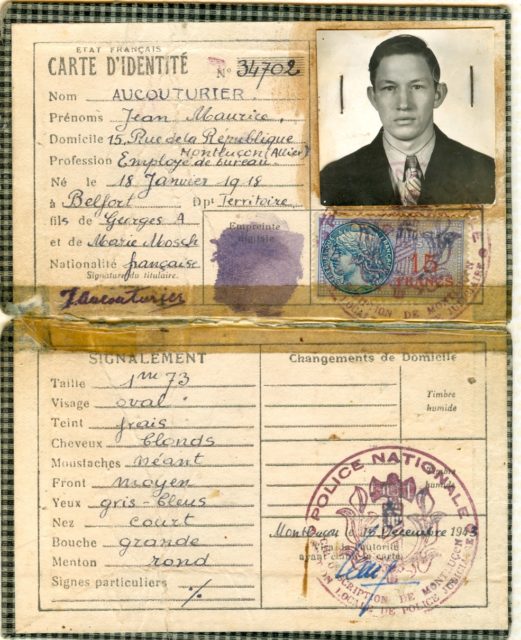

Clement “Clem” Dowler always knew he was going to die. “That was the only way to get through it,” he said. “To accept death and then keep on going.” Nonetheless, his luck managed to hold out during the summer of 1944. Just this past year, Clem was awarded the French Legion of Honor, France’s highest decoration, for his service during World War II.

Clem’s journey from manning a ball turret in a B-17 to fighting alongside the OSS in occupied France was extraordinary. He was born on May 9th, 1924 in Parkersburg, West Virginia. At age eighteen, Clem answered the call of duty, enlisting in the U.S. Army Air Corps. On the advice of his brother, he volunteered to be a truck driver. He recalled with a smile, however, that at that stage of the War the Air Corps “didn’t have much use for truck drivers.” Instead, Clem attended aerial gunner school and became a ball turret gunner with the 91st Bomb Group, 324th Squadron – the same unit as the celebrated crew of the Memphis Belle.

On April 28th, 1944, Clem’s bomber was hit by antiaircraft fire during a bombing mission over Avord, France. The gas tank between the No. 3 and No. 4 engine was in flames, and the crew had little time to escape. As Clem pried his way out of the ball turret, he saw both waist gunners bail out of the crippled aircraft. Unfortunately, he still had one major problem. He didn’t have his parachute.

Clem hunted through the interior of the aircraft where he was finally able to locate a “chest chute.” He knew he was running out of time, and he struggled with the harness as the bomber rapidly lost altitude and filled with smoke. Clem ran to the open hatch and managed to strap on his parachute at the very same moment that he hurled himself out into open air. He was the last man to bail out of his B-17.

Clem said the sensation of falling towards the earth felt similar to “sitting in a La-Z-Boy chair.” He explained that he just leaned back, relaxed, and felt the wind whistle through his uniform pants. He added, however, that there was one other reason he felt a feeling of calm wash over him. “To be honest,” he said, “I was just so happy to get out of that darned plane.”

As the ground came rushing up to meet him, Clem pulled his ripcord above treetop level and executed a delayed parachute release. In the final moments of his descent, he could see German machine gun fire being directed towards him and the other members of his crew. With few options, he reached up and grabbed his parachute lines, frantically twisting them back and forth, trying to make his body into a more difficult target. Just at that moment, two American fighter pilots swooped in at low altitude and strafed the machine gun positions. Clem watched the deadly effect of their tracer rounds as he came crashing to the earth. The resulting impact shattered his ankle and nearly knocked him unconscious.

Clem landed on top of the bombed-out runway of the airbase that he and his crew had been targeting that day. He limped and dragged himself to a nearby tree line. With fire and debris clouding the landscape, Clem crawled inside one of the many, large hedgerows that surrounded the perimeter of the base. There he found quite a surprise. Sitting next to him in that hedgerow was Herb Campbell, the waist gunner from his B-17.

The men huddled together for hours, listening as German patrols approached their position. They could hear rifle shots being fired randomly into the hedges around them. At one point, they could even smell the cigarette smoke of soldiers who were thrusting their bayonets into the underbrush.

To Clem’s horror, the Germans used other, more creative methods to try to flush out the airmen. Around midafternoon, Clem heard the distinctive sound of machinery. He crawled forward to see a German tank climbing up and over large sections of the hedgerow. A soldier with a flamethrower then stepped forward and sprayed down any remaining sections of foliage. “I was as scared as I’ve ever been,” Clem said. “That felt like the longest day of my life.”

Clem and Herb hid until nightfall, the German voices around them gradually receding into silence. Somehow, the men had managed to escape death twice in one day. Clem knew they had few options. They could turn themselves in and hope to be treated humanely, or they could attempt to walk out of France to Spain. Despite his broken ankle, Clem said the flamethrower incident made the choice a relatively easy one. The men stole a bicycle from a nearby farmhouse, and Herb slowly pushed Clem southward through the French countryside.

During the summer of 1944, Clem and Herb fought alongside several different French Resistance units. The pair traveled only at night, eventually locating a group of fifteen downed airmen encamped on the mountainside of Mont Mouchet. After the D-Day landing of June 6, 1944, German troops encircled the mountain. Their mission was to stamp out all resistance activities and then proceed on to Normandy. Clem recalled, “the woods were literally crawling with Germans.”

With little time to spare, Clem and the other airmen planned their escape. They said a quick prayer and divided into groups of two to try to slip through German lines. In the resulting confusion, Herb chose to pair up with another airman from the camp while Clem set off into the night. Unfortunately, Herb was later captured by advancing troops. He was first tortured and then executed by his German captors.

After the War, Clem always remembered how Herb had pushed him on that bicycle through the French countryside. He never forgot the debt he owed to his friend and crewmate. Nonetheless, Clem’s journey in occupied France was far from over. He traveled further south, all the while hoping he would soon run into American lines.

The first time Clem saw Lieutenant Roy Rickerson of the Office of Strategic Services, the man was standing in the middle of a French café in full American uniform, medals and all. At first, Clem couldn’t believe his eyes. “I thought it must be some sort of trap,” he said. “But then I realized I had nothing to lose.” Clem marched up to the officer, pulled out his dog tags, and introduced himself in English. “I told him I was a downed airman, and I wanted to get back under American control.” Surprised, Rickerson’s face slowly broke into a smile. He exclaimed, “Son, you have balls!”

Rickerson grew up in Bossier City, Louisiana, and was fluent in French. He and the other fifteen men of Operation Group Louise parachuted into the town of Devesset on July 17th, 1944. In the weeks that followed, they conducted continuous guerilla operations against German soldiers advancing to the front. A solidly built man, Rickerson explained that he often came into the city dressed in uniform. Not only did it “impress the French” and show that there was an American troop presence nearby, the trip also gave him an opportunity to “have a few free drinks.” Right at that moment, Clem realized he wasn’t dealing with an ordinary soldier.

Clem showed no hesitation in asking the lieutenant if he could join his unit. Nonetheless, a local French Resistance leader who accompanied Clem to the café viewed the airman as a bit of a status symbol and opposed any attempt he made to leave. Clem briefly described the situation to Rickerson who responded that he would take care of it. He strode right over to the man, leaned in close, and held out his hand. The handshake went on for over a minute while the two discussed, Rickerson smiling the entire time. Finally, he let go and walked back across the room. Over his shoulder, Clem could see the much smaller Frenchman wringing his hand in pain. “No problem,” Rickerson said. “He was tickled to death to see you go.”

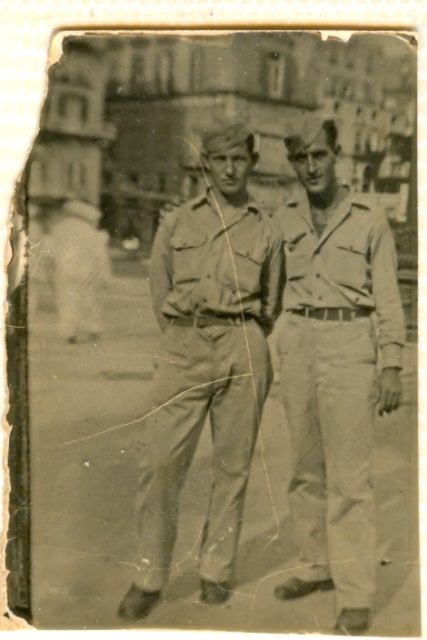

Clem arrived at the old farmhouse near Devesset and at first thought it was abandoned. “There wasn’t a soul in sight,” he said. As he walked further into the property, it opened up into a large pasture with tall grass and shrubs. Rickerson stopped him there and looked around slowly. He turned to Clem and said, “I want you to meet my men.” The lieutenant whistled, and armed soldiers from Operation Group Louise gradually rose from their positions. They had grass and leaves attached to their uniforms. Clem shook hands with all of them, introducing himself and listening to their names in response – men with surnames like Boucher, Pelletier, and Gagnon. Clem remembered that the welcome was quick and friendly. Afterwards, each man turned and walked back to his position. “It was clear they had a job to do.” Clem would soon discover that these OSS soldiers weren’t like average men. They took incredible risks and moved with a great deal of confidence in battle. “I’d never seen anything like them,” Clem said. “They were absolutely fearless.”

Operation Group Louise was composed of Army regulars who volunteered for particularly hazardous duty. Rickerson and his troops trained stateside for months before finally deploying in support of the French invasion. Their mission was to strengthen underground resistance efforts, to boost the morale of the French people, and more importantly, to harass the enemy at any opportunity. Part of a larger contingent of six operational groups dropped into the Ardèche department, the soldiers of Louise used hit-and-run ambushes to inflict maximum casualties on the enemy. These men were forced to overcome significant challenges almost from the beginning. The drop zone near Devesset was improvised after the Germans attacked the original location three kilometers away. It was littered with rocks, cliffs, and high-tension power lines. One soldier broke his leg in two places during the jump. To further complicate matters, the Germans had dropped paratroopers dressed in American uniforms on the very same drop zone just a few days before. As a result, Rickerson and his men found themselves greeted by angry French civilians armed with pistols.

Clem liked Rickerson the moment he met him. Intelligent but street smart, the American OSS lieutenant had the ability to talk his way out of dangerous situations. Moreover, as Clem would soon see, Rickerson never shied away from a good fight. As the two walked deeper into the woods beyond the farmhouse, Rickerson explained that he and his men were trained to “live off the land.” They didn’t want any special attention and tried as best they could to blend in with their surroundings. To his amazement, Clem started to make out the silhouette of some sort of manmade structure a few yards away. Although primitive in construction, Clem saw that it was a small shelter made from timber and brush from nearby trees. Without warning, Rickerson reached through the branches and pulled back a makeshift door covering the entrance. “You can bunk here while you’re with us,” he said.

Clem’s new barracks left a little to be desired, but he quickly learned that the men of Operation Group Louise had plenty of food and weapons. The soldiers were supplied by airdrops from their headquarters in North Africa. In the days after Clem’s arrival, the Allies dropped K-rations, cigarettes, and ammunition. They also parachuted in four 37mm cannons for use in ambushes against the Germans. One thing the unit lacked, however, was a rifle for its new arrival. Thus, Clem armed himself with a Colt .45 pistol and prayed that a new rifle would arrive soon.

Rickerson’s men didn’t fight like traditional soldiers. Clem realized that their brand of warfare was intended to keep the enemy off balance. They used plastic explosives to sabotage bridges and derail trains. They cut communication lines and destroyed any type of infrastructure that might assist the enemy. What Clem could never forget, however, were the deadly ambushes they conducted against advancing German forces. The OSS soldiers showed Clem how to use mud and berries to camouflage his face during operations. They also gave him basic instruction on small unit tactics. The rest he was forced to learn through “on the job training.”

Clem participated in multiple ambushes during his time with the OSS. He and the men of Operation Group Louise would move in close to the enemy, using concealment and the element of surprise to their advantage. They would wait until the Germans were right on top of them, and then they would open up with everything they had – bazookas, small arms, and British made Gammon grenades. Clem remembered that the 37mm cannons were also utilized during a number of operations. The men towed the cannons to high ground with horses and trucks. When a German convoy was directly downhill from their position, they would knock out the lead vehicle with a cannon round. All the other vehicles behind it were then pinned in.

Clem Dowler in his own words during an interview for the Library of Congress

Despite the many years that have passed since that summer of 1944, there is still one operation that stands out to Clem. On that particular day, he was certain that his luck had run out. The OSS set up an ambush in the hills overlooking the city of Vallons. They estimated that a force of 1,500 Germans would soon be moving through the area. Instead of the reported 1,500 soldiers, however, their numbers were closer to 10,000. The Germans started moving at daybreak, and a fight immediately broke out. The forward observer could see a number of Germans hit in the arms and legs, and the men could hear the wounded soldiers’ cries from their position. Other OSS soldiers had crept close enough to throw hand grenades into approaching vehicles.

Rickerson assigned 40 French Resistance fighters to act as security on their left and right flanks. Unbeknownst to him, these local fighters had withdrawn leaving all of the men exposed. Clem recalled that he was feverishly feeding ammo into the 37mm cannon when his position was overrun. On the hill to his right, the Germans had managed to move up a machine gun and mortar. The ground exploded into great clods of earth as the gunners directed their fire at his position. Two Frenchmen next to him were hit in the chest as the German gunners raked their fire back and forth. Clem tried to find cover while blindly emptying his .45 pistol towards the sound of the machine guns. Vastly outnumbered, Rickerson gave the order to retreat.

The men crawled on their bellies to escape the enemy while Rickerson and another soldier laid down covering fire. They sighted in on the machine gun and knocked it out with a bazooka. Just at that moment, Clem realized that more German soldiers were maneuvering on his right. He moved quickly down the hill in an attempt to protect against the impending attack. Rickerson again went into action when two OSS soldiers were pinned down. He crawled nearly 200 yards through a hail of automatic weapons fire to where he previously dropped the bazooka. He picked up the weapon and opened fire, silencing yet another enemy machine gun nest and allowing his men to escape.

Clem understood that the Germans had come over the mountains to cut off their escape. Thus, he and the other men left behind their vehicles and slipped through the German lines by foot. All of the soldiers of Operation Group Louise miraculously survived the battle. Nonetheless, the Germans captured two of the 37mm cannons along with a large portion of their equipment. The men walked nearly fifteen miles to a rendezvous point where they attempted to gather their strength. Filled with adrenaline, Clem slept fitfully that night. Although Rickerson posted sentries outside the camp, Clem knew they stood no chance against an overwhelming enemy force.

At daybreak the next morning, Rickerson awakened his troops. He looked them each straight in the eye and said, “Now, let’s go back up and take that hill.” Clem remembered that not a single man grumbled or complained. In fact, they all immediately set about gathering their weapons. Clem reached down and passed his Colt .45 pistol back and forth between his hands. He knew he was drastically outgunned, but he hoped that he “would survive and get back to the states in one piece.” As the soldiers made the long trek back to Vallons, Rickerson and a few other men went ahead to conduct reconnaissance. What they found surprised them. The Germans had pulled out overnight. More importantly, they had left behind the two 37mm cannons.

At the beginning of September, Rickerson was chasing the German army further and further north. He also received orders to move his unit to Lyon which had just been liberated. Although it was a difficult decision, Clem knew that the time had come to say goodbye to the men of Operation Group Louise. The air war was raging over Europe, and Clem felt duty-bound to get back to his airbase in England. He explained the situation to Rickerson who immediately provided him with a map that depicted the advancing American lines. Rickerson also handed Clem a handwritten letter. Clem opened it and slowly read its contents. In matter of fact terms, Rickerson described Clem’s service to the unit. The letter read, “Sgt. Clement Dowler attached himself to an American OSS operational group in the French interior upon being shot down. He has rendered exceptionally good services to this unit and in no time has he failed to carry out an order from this command. We recommend him highly for his good service.” As Clem turned to leave the camp, all of the OSS soldiers stood and saluted.

Clem continued south until he found himself traveling against a steady stream of American soldiers advancing to the front. At a small village, he managed to requisition a sedan with the keys still in the ignition. He drove slowly against the flow of men and supplies, pulling the sedan over and waving whenever he had the chance. Eventually, he reached the port city of Avignon where an American officer arranged for his flight back to England. As Clem boarded the B-25 that would fly him back to his squadron, he felt an overwhelming rush of emotion. His thoughts turned to his family. He was so grateful to have the chance to see them again, and he couldn’t wait to get back to the states. He next thought about the friends he had lost along the way, as well as the fearless soldiers of Operation Group Louise. He hoped these brave men would survive the many battles to come.

Finally, Clem considered one important question that had been plaguing him ever since he set foot on that plane. He glanced nervously around the interior of the aircraft and wondered aloud to anyone who would listen, “Where the heck is my parachute?”

From McKay Smith for War History Online

* Author Bio: McKay Smith is an attorney with the U.S. Department of Justice, National Security Division. He is also an adjunct professor at the George Washington University Law School and the George Mason University School of Law where he teaches courses on government oversight and internal investigations. Prior to joining the Department of Justice, Smith was a senior inspector with the Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Justice or the United States. The grandson of Clem Dowler’s B-17 navigator Ray Murphy, Mr. Smith would like to thank Mr. Dowler for his wonderful friendship and for his exceptional service to his country. This article will also be featured in the forthcoming issue of The OSS Society Journal.