From the 4th to 8th of May 1942, the Japanese and American fleets in the Pacific made history. For the first time ever, a naval battle took place in which neither fleet came within sight of the other.

It showed where naval warfare was heading in the 20th century, with planes and later rocketry meaning that fleets could strike across the horizon. As a strategic encounter, it was costly but indecisive.

Background to the Battle

In the spring of 1942, the Japanese controlled most of the South Pacific. Having seized many of the island chains from East Asia down to Australia, their next stops would be Guadalcanal and New Guinea, from which they could launch an invasion of Australia.

Though not a major world power, Australia was a significant contributor to the Allied cause. Her soldiers were fighting alongside the British in North Africa. Her fleets sailed alongside the Americans in the Pacific.

Australia was an important part of the trade and supply network that kept American forces in action against Japan. The Allies needed to stop the Japanese before they gained control of the whole of the western Pacific.

The Fleets

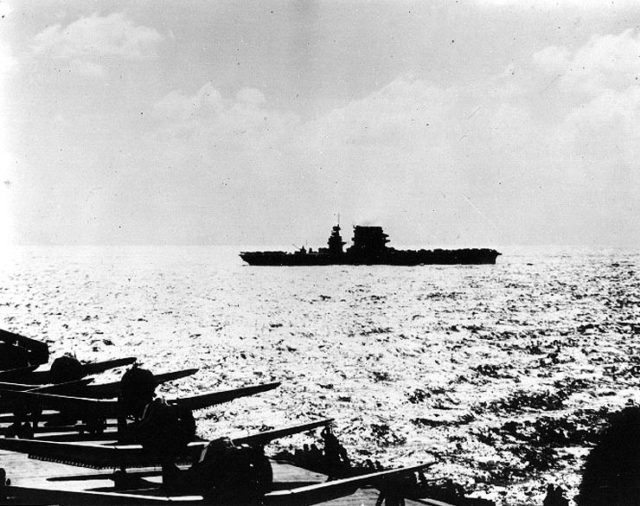

The Americans sent Task Force 17 under Rear-Admiral Frank J. Fletcher to the Coral Sea, to stop the advance of the Japanese fleets. Task Force 17 had two aircraft carriers – the Yorktown, Fletcher’s flagship, and the Lexington, which had started life as a cruiser before being converted into a carrier. Unlike their opponents, the Americans had radar in their fleet.

They carried three types of aircraft – 72 obsolete Douglas SBD-2 Dauntless dive-bombers; 36 Douglas TBD-1 Devastators, torpedo bombers with a poor ‘climb’ and limited range; and 36 Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighters, whose role was to counter enemy aircraft and protect the bombers. The planes from the Yorktown carried new equipment to help identify friend from foe in the chaos of aerial combat.

Opposing them was Rear-Admiral Takagi’s force – the aircraft carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, both veterans of the Pearl Harbor attack, two cruisers and a destroyer screen. On the Japanese carriers were 42 Aichi D3A Val dive-bombers, 41 Nakajima B5N torpedo planes, and 42 Mitsubishi A6M5 Zeros to provide fighter cover. These planes were technologically superior to those of the Americans.

Finding the Fleets

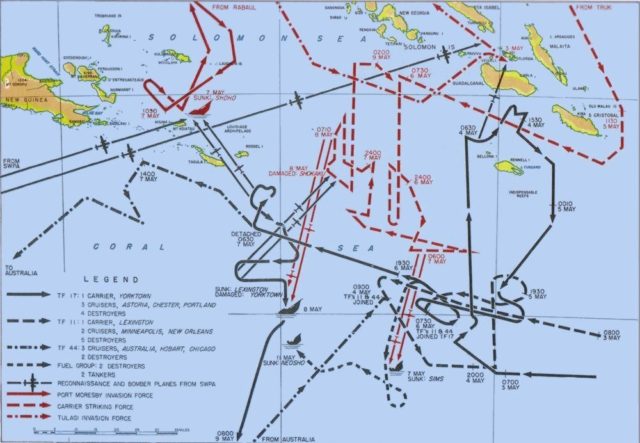

On 4th May, Takagi was near the island of Tulagi, where Japanese forces had landed the previous day as part of taking Guadalcanal. Fletcher decided that it was time to counter the Japanese advance. He launched 28 Dauntlesses and 12 Devastators to attack craft around the island, sinking a destroyer, three minesweepers, and various support vessels.

Takagi sailed his fleet west to find the Americans while an invasion force under Rear-Admiral Kajioka headed towards the Coral Sea and its eventual destination of New Guinea. Over the next two days, scout planes sporadically spotted the opposing fleets, but there was no further bombing, only positioning.

7 May – Carrier Combat Begins

On the morning of the 7th of May, American reconnaissance spotted the invasion fleet. Bombers were launched and sank the Shoho, the only carrier in Kajioka’s invasion force. Six American planes were lost, but the invasion fleet now had no air cover and was completely reliant on Takagi.

Meanwhile, a smaller mixed Australian and American fleet under Rear-Admiral Crace blocked the invasion fleet’s advance at the Jomard Passage. Takagi’s torpedo planes tried to attack this fleet, but it was protected by poor weather and Wildcats from the Lexington. Nine bombers were destroyed for the loss of two fighters, and the Japanese planes retreated without hitting the fleet.

With Crace still blocking the passage, the vulnerable invasion fleet was forced to withdraw.

Now it was down to Fletcher and Takagi to fight for control of the Coral Sea.

8 May – The American Attack

The morning of 8th May saw bright sunshine over Fletcher’s fleet and clouds over Takagi’s, giving the Japanese a defensive advantage. Around 0600, both fleets sent out scout planes to find each other, and once their locations had been radioed in the bombers were launched.

Arriving at the Japanese fleet around 1030, the first American planes hid in the clouds while they waited for the rest to arrive. As the Shokaku emerged from beneath cloud cover the Americans descended.

Japanese fighters rose to disrupt the American attack while the Shokaku weaved rapidly through the sea to throw off her attackers. Only two bombs hit, and none of the torpedoes found their mark. But those two bombs were enough to make the flight deck unusable, preventing more fighter launches, and to start a fire that spread through the ship. The Shokaku was forced to retreat while its planes transferred to the untouched Zuikaku.

8 May – The Japanese Attack

The Japanese reached the American fleet at 1055. Flying high, they avoided the destroyers and the small air screen the Americans were able to field. Diving to attack height within the American defences, they were hit by Dauntlesses hastily pulled back to try to stop them.

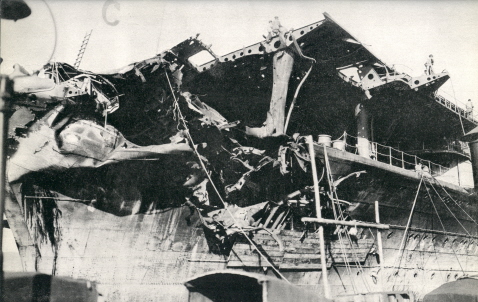

The Yorktown dodged the first wave of attacks, but a bomb from the second wave punched through the flight deck and set the ship on fire. The Japanese then turned their attention to the Lexington. Hits from two torpedoes and two bombs left the ship listing badly and with her boiler rooms flooded.

Aftermath

The battle was effectively over, but at what cost?

Between planes shot down and those that had to be ditched because they could not land on the Shokaku, the Japanese lost 80 planes, while the Americans lost 66. 900 Japanese sailors and flyers were dead, compared with 543 Americans.

Escaping fuel caused two massive explosions on board the Lexington. As fires spread, the crew abandoned ship, and she was finally sunk by torpedoes from an American destroyer.

The Battle of the Coral Sea was a ground-breaking action but did little to turn the tide of war. Neither side suffered significantly greater losses in men and planes, and both saw carriers crippled. The invasion fleet was turned back but not destroyed. The advance on New Guinea would continue.