One campaign changed the direction of the Second World War: the Battle of France. The period leading up to the engagement was known as the “Phoney War” and it had lulled the Allies into a false sense of security. Taking advantage of this, Germany developed a strategy based on a concept known as Blitzkrieg – or “lightning war.”

By circumventing the heavily-fortified Maginot Line, the military aimed to catch the Allies off-guard. All this preparation paid off, with Germany gaining control of not just France, but also the Low Countries by the end of June 1940.

Germany’s Blitzkrieg strategy

The German military’s Blitzkrieg strategy was a marked departure from traditional warfare. It emphasized speed, coordination and surprise, and its integration of tanks, mechanized infantry and air support (all coordinated via radio) enabled the German forces to penetrate deep into enemy territory with unprecedented speed. The approach aimed to disrupt and surround the Allies -and it did just that.

The first use of Blitzkrieg tactics came with the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, and it continued to see success throughout World War II. While largely unmatched, there was one strategic stance it couldn’t win again: an organized defense that used a combination of infantrymen and guns to target the rear of mobile units.

Diverting Allied troops away from the Maginot Line

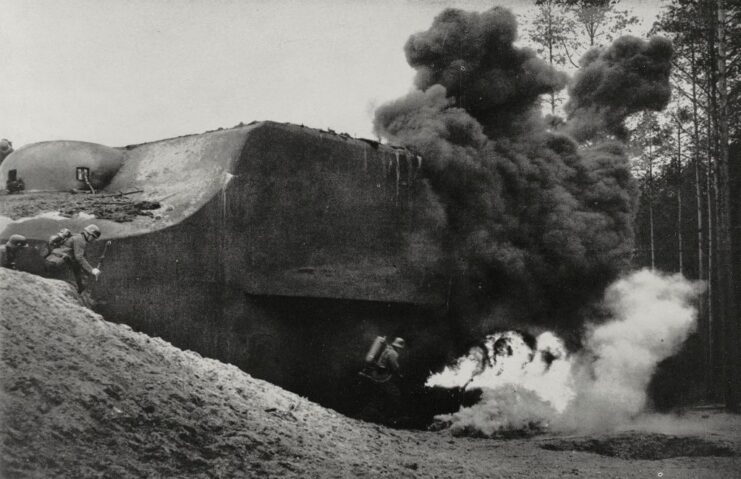

The Maginot Line was a series of defense structures that were built along the French-German border in the aftermath of World War I. Stretching across 280 miles, it consisted of underground bunkers, forts, machine gun batteries and minefields, with the majority of these being constructed with concrete and steel.

Unsurprisingly, the Maginot Line was a central part of France’s defensive strategy, as it was believed an attack by Germany would come via the countries’ border. However, the latter’s military was aware French officials assumed this and devised a strategy that would see them bypass the line entirely by moving through Belgium and the Netherlands, effectively rendering it useless. As well, this plan would serve a dual purpose of diverting attention away from other access points.

In the aftermath of the invasion of Poland, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), supported by Belgian troops and France’s most modernized units, amassed in the Low Countries. On May 10, German troops made their advance. The first strike on Belgium was an attack by airborne troops on Fort Éban-Émael, and the enemy’s success led the Belgian Supreme Command to order that those stationed there withdraw to the Koningshooikt-Wavre Line (KW-Line).

The German advance on Belgium consisted of three groups. The first saw troops move through the Netherlands and northern Belgium in a pincer movement, with the same strategy occurring in the south, into Luxembourg. We’ll get into the third group soon.

The Netherlands witnessed a similar defeat, with the country’s air force losing half its numbers on the first day of combat. Various bridges were also captured. While Dutch troops attempted to stop any additional German soldiers entering the country, they were unsuccessful, forcing Queen Wilhelmina to flee and establish a government-in-exile in Britain.

Breaking through the Ardennes

With the majority of the Allied forces aiding in the fight in Belgium, the third group of German troops moved through the largely undefended Ardennes region. While they ran into resistance near Sedan, it took the 60,000-strong force just a few days to defeat the outmatched 20,000 French soldiers they encountered.

The offensive through the Ardennes, spearheaded by Gen. Gerd von Runstedt’s Army Group A, was a masterstroke of military strategy, exploiting a defensive gap left open by the Allies. The maneuver not only bypassed the Maginot Line, but it also took advantage of the rough terrain in the region, which the French had deemed unsuitable for a large-scale armored assault.

The surprise of and speed with which the advance through the Ardennes was conducted shattered the Allied front, and it set the stage for a rapid push through France that saw the Germans reach the English Channel, near Abbeville, just a week after they’d launch their assault. By May 26, all Belgian and French ports north of the Somme (except for Dunkirk) had been captured, with Belgium surrendering just two days later. The Netherlands had surrendered quite a bit earlier, on May 15.

Dunkirk Evacuation

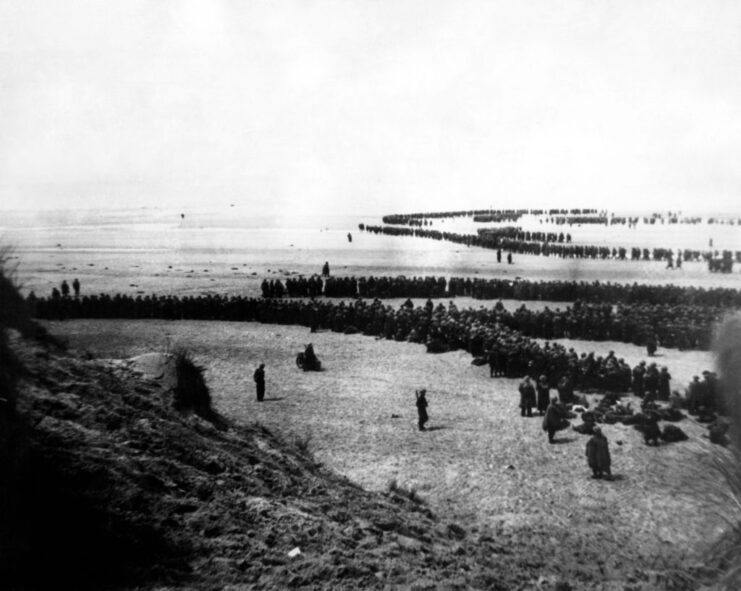

With the Germans making quick work of France’s defensive strategy, the Allies, primarily made up of the British Expeditionary Force, found themselves pushed back to the port of Dunkirk. Realizing swift action needed to happen to save them from being taken as prisoners of war (POWs) or, worse, killed, the British Royal Navy command in Dover, under the command of Vice Adm. Bertram Ramsay, organized an evacuation.

The Dunkirk Evacuation – codenamed Operation Dynamo – was among the most remarkable episodes of the Battle of France. Beginning on May 26, 1940, and lasting until June 3, it saw over 800 ships (some sources say 900) rescue 338,226 troops. A unique aspect of this operation was that it wasn’t just naval vessels involved. Civilian boats – known as “little ships” – also took part, reaching areas the larger vessels couldn’t.

Speaking about the evacuation, Royal Artillery Gunner Allan Barratt said:

“It was dusk by the time we reached Dunkirk and we could see the fires blazing fiercely, buildings silhouetted in the red glow, it looked frightening… the troops could be seen in lines like dark snakes extending down into the sea itself, they appeared to be wading out to small boats some distances from the water’s edge. In front of us too, small boats were picking up men off the beach and taking them out to ships waiting offshore.”

While the Allies had to evacuate from France, the rescue of so many British soldiers ultimately boosted morale and support for the war effort in Europe – a notion that came to be known as the “Dunkirk spirit.”

Launching Fall Rot – the second phase of the Battle of France

With the Allies evacuated and the fall of Belgium and the Netherlands, it was time for Germany to place its full attention on the capture of France. Dubbed Fall Rot (“Case Red”), it began with troops heading south, with Paris being the end point.

The regions around the Aisne and Somme were the first to be attacked, along with the Maginot Line. The latter offensive, officially known as Operation Tiger, began on June 13, 1940, and saw the German 1st Army strike between St. Avold and Saarbrücken, with subsequent assaults taking place along other areas of the defensive line.

Before long, the Maginot Line’s defenses had collapsed, with many of the forts along it either surrendering or being captured. This ultimately allowed for the areas around the Rouen and Seine also being overrun.

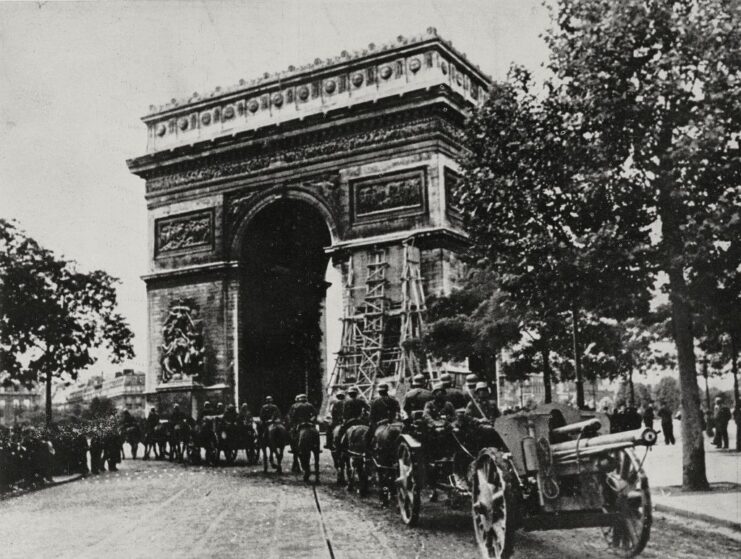

Paris – and France, in general – fall to the Germans

The capture of Paris by the German military came in mid-June 1940, marking a somber milestone in the Battle of France. Troops launched a major offensive on the city on June 9, with the government ultimately relocating to Bordeaux to avoid capture. The French soldiers tasked with guarding the capital city withdrew on June 13, to prevent its destruction, with the Germans moving in the following day.

The fall of Paris didn’t just deliver a big blow to French morale, but also demonstrated the extent to which the Germans came to dominate Western and Eastern Europe in the early stages of the Second World War. Paris, with its heritage and culture, quickly became a symbol of the tragedy of the conflict, its occupation serving as a dark chapter in the history of France and Europe as a whole.

Following the fall of France, the 192,000 Allied troops who’d been sent in following the Dunkirk evacuations, as well as civilians, were rescued as part of two amphibious operations, Cycle and Ariel.

Signing of the Second Armistice at Compiègne

The Battle of France officially ended with the signing of the Second Armistice at Compiègne on June 22, 1940. The capitulation of the nation had taken just six weeks, and the agreement was signed in the same railway carriage where the German surrender was formalized at the end of World War I.

Several terms were laid out in the armistice. While Germany initially wanted the French Navy to be completely removed from the conflict, it ultimately agreed to its disarmament. A small French Army was allowed to remain active, but fighting in French North Africa needed to stop. The decision was also made to keep some form of government in place, to reduce the amount of resources needed in the country.

The northern and western regions of France fell under German control, while the south was governed out of Vichy. Led by famed French Army commander Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain, the government claimed neutrality, but was, in reality, a puppet state aligned with Germany, given the conditions set out by the armistice. It also had limited control of some German-occupied areas.

The Vichy regime was taken over by Germany in November 1942, in retaliation for the Free French forces, led by Gen. Charles de Gaulle and his government-in-exile, fighting in North Africa.

How did the Battle of France impact World War II?

The ramifications of the Battle of France extended beyond its immediate aftermath. The country’s swift defeat sent shockwaves across the international community; the German victory significantly shifted the balance of power in Europe, emboldening the nation and its allies while forcing the Allies to reassess their military strategies.

In terms of those living in France, they faced several hardships under the German occupation. Food rationing became common, as was violence at the hands of their occupiers. Propaganda and censorship became the norm, as did Tuberculosis and illnesses among children. In an effort to combat the enemy troops, a Resistance movement popped up to conduct clandestine operations.

It wasn’t until June 1944, with the Allied invasion of Normandy, that France began the process of being freed from the grasp of its German captors. Over the subsequent months, the Allies pushed further inland, with Paris liberated that August – but not without some concerns from Gen. Omar Bradley and Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. Charles de Gaulle was able to convince the pair to keep moving into the capital city.

More from us: Battle of Moscow: A Critical Turning Point In the Fight along the Eastern Front

By May 7, 1945, when the war in Europe officially ended, and the German surrender the following day, France was free of its occupiers and back under French control.