Before the threat of war in the Pacific and the outbreak of World War II, Wake Island was a stopping off point for vacationers aboard Pan American flights to and from the Orient. Bird watching, sports fishing, and swimming were the principal activities on the ten-mile-long island.

Situated roughly halfway between Hawaii and Japan and under the control of the USA, the atoll became a strategic dot in the vast Pacific Ocean. Early in 1941, almost frantic work was underway to complete an airstrip with defensive fortifications.

About 1150 civilian construction workers joined 450 Marines, a few Navy men, and a five-man Army radio section in the effort to establish a base of operations close enough to Japan for American bombers to strike the Japanese-controlled Marshall Islands should such action be necessary.

Across the International Date Line, December 7, 1941, dawned in Hawaii. An Army radioman caught the broadcast at 7:00 a.m. December 8 at Wake Island. “Hickam Fields has been attacked by Japanese dive bombers. This is the real thing.”

The personnel on Wake knew a war was looming, having installed five-inch anti-aircraft guns and stockpiled ammunition. Twelve Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighters were standing by with Marine pilots at the ready. Within minutes after the radio message, the American flag was raised, as it was every day. But this day the bugle call of “General Quarters” gave men pause. They stopped all activity, stood at attention, and saluted the flag.

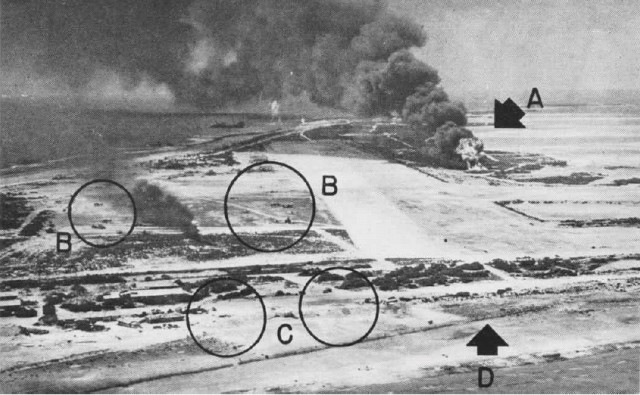

Then a sound caused the construction crews to run for cover and the Marines to head toward the guns. The deafening drone of thirty-six Japanese Mitsubishi G3M2 Nell bombers flying over Wake in strict formation assaulted their ears.

The fragmentation bombs and machine gun fire spewing from the aircraft ripped and tore at the tiny island. Pearl Harbor and Wake Island were being attacked almost simultaneously. Where the Pearl attack ended after a few hours, for several days the Japanese bombarded Wake from the air.

On December 11, a Japanese invasion task force steamed toward the beaches of Wake Island. Marine gunners played them like the sports fish in the water beneath the war machines. They watched the cruiser and six destroyers carefully and blasted them with the five-inch naval guns at 4500 yards.

One destroyer was sunk. Several of the other ships were damaged. The flotilla retreated with the knowledge there were true fighting men on Wake Island.

After the initial raid was fought off, American news media reported that, when queried about reinforcement and resupply, Cunningham was reported to have quipped “Send us more Japanese!” In fact, Commander Cunningham sent a long list of critical equipment—including gunsights, spare parts, and fire-control radar—to his immediate superior. It is believed that the quip was actually padding that is a technique of adding nonsense text to a message to make cryptanalysis more difficult.

The Japanese kept hammering at the island defenses, and ten days later the only surviving Wildcat fighter was lost. Pilots were assigned rifles and bayonets. A renewed enemy landing force sailed onto the beach, and 900 trained infantrymen invaded during the night of December 23. Construction workers and Marines fought side-by-side with everything they could, but by dawn, it was clear that there were too many Japanese.

The Commander Cunningham radioed Pearl Harbor. “Enemy on island. Issue in doubt.”

The Commander would later be quoted as saying, “I tried to think of something…We could keep on expending lives, but we could not buy anything with them.” He gave the order to surrender. The surviving eighty-one Marines and eighty-two civilians obeyed but destroyed everything they could find that the enemy could use as a weapon and disabled all the equipment they could. The Japanese claimed the victory at a great price.

Two destroyers and one submarine had been sunk by the Americans. Seven other ships were damaged, and twenty-one aircraft were shot down. The total lives lost by the Japanese was close to 1000. Their leaders were furious and exacted revenge on the prisoners. Stripped and tied with wire in such a way a sudden movement would cause strangulation, soldier, and civilian alike were made to sit in the sun on the concrete they had recently poured.

No water or food was given to them for two days. At one point, the captors installed machine guns near them, for a mass execution, they imagined. But, at last, they were fed spoiled and unsavory bits of food, and instructed to put quickly on clothing but not necessarily their own. Marines donned civilian pants, and construction workers were in khaki.

A spit polished, crisply white uniformed Japanese commander addressed the prisoners. An interpreter informed the group “the Emperor has graciously presented you with your lives.” One unfazed Marine replied, “Well, thank the son of a b**** for me!”

Toward the middle of January 1942, a merchant ship laid anchor at Wake Island. The prisoners were transported to China by ship. But as they were shoved toward the ship, two columns of Japanese sailors with clubs and belts formed and the prisoners were made to run between them, enduring savage beatings.

They were stuffed into the ship’s hold, became despondent, and were savagely treated. Shuffled about China and Japan, the Marines regained their spirit and endured tremendous hardships for the next three years. Eventually, after the atomic bomb attacks and Japanese surrender, they were rescued.

Ironically, the prisoners left on the island received a worse fate, working as slave labor until October 1943. Then on 5 October 1943, American naval aircraft from Yorktown raided Wake. Two days later, fearing an imminent invasion, the Japanese Rear Admiral Shigematsu Sakaibara ordered the execution of the 98 captured American civilian workers who had initially been kept to perform forced labor.

The 98 were taken to the northern end of the island, blindfolded and executed with a machine gun.

One of the prisoners (whose name has never been discovered) escaped the massacre, apparently returning to the site to carve the message 98 US PW 5-10-43 on a large coral rock near where the victims had been hastily buried in a mass grave. The unknown American was recaptured, and Admiral Sakaibara personally beheaded him with a katana. The inscription on the rock can still be seen and is a Wake Island landmark.

Before the final rescue, in July 1945, a strange thing happened in the prison camp. Japanese officers provided a formal dinner for the American officers, offering toasts and speaking of friendship. In the end, a high-ranking Japanese officer proposed a toast to “everlasting friendship between America and Japan.”

His side of the table smiled, nodded and waited for the American response. The skeleton faces of the Americans were still. At last a Major stood and said lightly, “If you behave yourselves, you’ll get fair treatment.”

The proverbial tables had turned. And the Americans promise of fair treatment far outshines the despicable behavior of the Japanese. On August 16 the prison guards were gone. Small children were assigned to protect the prisoners from possible civilian attack.

On September 1, the Marines patched a makeshift American flag together and hoisted it into the air. Supplies were air-dropped and at last, the 1st Cavalry Division liberated the prisoners. The war was over.

After the war, Sakaibara and his subordinate were sentenced to death for the massacre of the 98 and for other war crimes. Several Japanese officers in American custody had committed suicide over the incident, leaving written statements that incriminated Sakaibara.

Admiral Sakaibara was hanged on 18 June 1947. Eventually, Tachibana’s sentence was commuted to life in prison. The murdered civilian POWs were reburied after the war in Honolulu’s National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, commonly known as Punchbowl Crater.

By Elaine Fields Smith