In December 1943, a group of largely untested Canadians went up against German forces in the Italian town of Ortona. The result was a bloodbath so intense that the media called it the “Italian Stalingrad.” Sadly, it could have been either avoided or mitigated had two Allied generals just cooperated with more good will.

On 10 July 1943, the Canadian 1st Infantry Division (under Major General Chris Vokes) were headed for Sicily. A volunteer group, none had seen combat, yet they were about to land on Axis territory. They were there as part of Operation Husky – an attack on Italy which began on the evening of July 9.

The Americans (under General George Smith Patton, Jr.) were to land on the west, the British (under Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery) to the east, and the Canadians (who were also under Montgomery) in the middle. It didn’t turn out well.

German U-boats sank three Canadian ships, killing 60 men. With those ships went 500 vehicles, including several ambulances and 40 cannons. As they attacked the island, however, their luck changed as the landing site was only lightly defended. The Italians troops position there had no stomach for the war, and allowed the Canadians to take over 500 of them as Prisoners of War.

They were greeted as liberators in the nearest towns, lulling them into a false sense of security. It wouldn’t last. Hitler had ordered Italy to be held at all costs. Worse, the rivalry between the Americans and the British had begun.

Patton and Montgomery hated each other and were in a competition to reach Messina first. Located on the northern tip of Sicily, it was the gateway to the Italian mainland. Patton got there first, infuriating Montgomery, but it was the Canadians who would pay the price.

In Rome, the government was in a full-blown panic. The Allies had been bombing the Italian mainland, including Rome, causing shortages of food and material. Fed up, they ousted and imprisoned Mussolini on July 25. Then they began negotiating with the Allies as the latter took Messina in early September, crossed the Strait of Messina, and landed at Reggio on the mainland. On September 8, the government surrendered, then fled as Hitler ordered Rome taken.

The Germans held their line to the south of Rome, from Cassino to the southwest, to Ortona to the northeast. But instead of joining the American attack on Cassino (which was closer to Rome), Montgomery headed for Ortona. From there, he planned to head west to reach Rome before Patton.

What he failed to consider were the heavy rains. Tanks and heavy equipment were bogged down in the thick mud, delaying the British troops. This forced the Canadian regiment to lead the attack across the Moro River. They reached it at midnight on December 5, where they were picked off by elite German troops of the 1st parachute division – men who had seen combat in Africa.

Ortona was just across the river, but the Canadians first had to cross vineyards strung with barbed wire. Dotted throughout were stone farm houses from which the Germans picked them off. It took the Canadians three days and heavy losses to cross the Moro, but worse was to come.

Between the river and Ortona was a ravine some 200 yards deep and 200 yards wide, which they called the “gully.” On the other side were more German troops. To cross would be suicide, but Montgomery didn’t care. After three days and even more losses, they made no headway.

On December 11, the Royal 22nd Regiment and a battalion of the Armored Regiment targeted Casa Berardi – a large 3-story farmhouse near the gully’s end and close to the main road leading to Ortona.

As they neared the house, however, they were met by a panzer division. Using smoke for cover, they managed to take the Germans out with anti-tank weapons. Captain Paul Triquet’s C Company took Berardi on the afternoon of December 14, but they were so decimated, they could go no further. Of the 35 to 40 who began the attack, only 17 were left.

Vokes wanted a new strategy, but Montgomery refused, since he considered the Canadians expendable. He ordered four rifle companies with 320 men to take the crossroads north of the gully. They secured it on December 18, but at a cost of 162 dead.

Montgomery believed that the Germans would finally retreat. What he didn’t know was that they were ordering all of the residents to leave. Then they began destroying buildings to block tanks and funnel the Canadians into streets they had secured.

Masters of mines, explosives, tripwires, and booby traps, they made the Canadians pay for every door they opened, every threshold they crossed, and even furniture and bricks they picked up. Since the buildings of Ortona shared walls, the Canadians developed a technique called “mouse-holing” to deal with fighting at such close quarters. They’d blast holes in walls, then fire at Germans on the other side.

By December 24, there was still no lull in the fighting, so the media called Ortona the “Little Stalingrad.” On Christmas day, both sides fought in shifts so that some could enjoy mass and a meal before diving back into battle. German media also focused on the event, so Ortona became a matter of prestige.

On December 27, 24 men of the Edmonton Regiment were lured into a building which was detonated. Only 4 survived. In retaliation, they shelled a building housing 40 or 50 Germans. Some suggested pulling out, but Vokes felt that far too many Canadians had died, so he ordered the fighting to continue.

Although Hitler gave the order to hold Ortona at all costs, the Germans had had enough. Late that night, they began retreating in small, orderly groups. The following morning, the Canadians were met with silence. It took them a while to realize that the Germans had left.

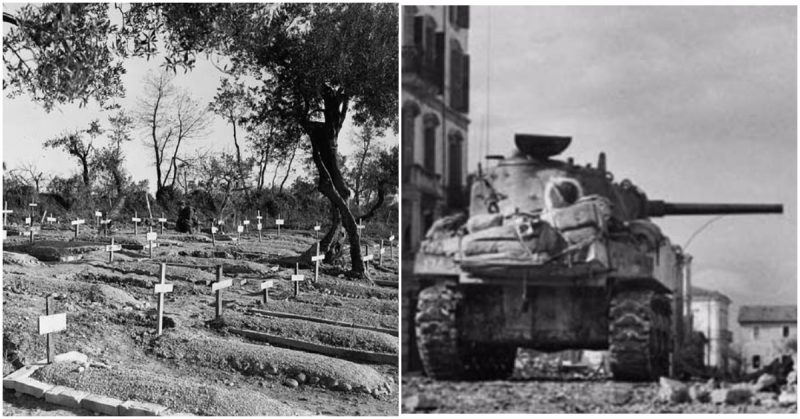

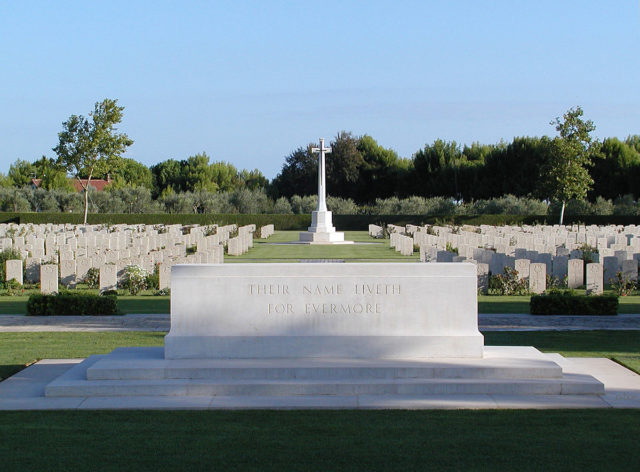

By then some 2,600 Canadians and over 800 Germans had lost their lives. While most of the residents had obeyed the evacuation order, about 1,300 chose to stay and paid with their lives.

On 25 December 1998, German and Canadian survivors of the battle reunited at Ortona to bury the past and forgive what could not be forgotten.