The Guadalcanal Campaign was the first major American offensive of WWII. During the fighting, American forces witnessed the dedication and ferocity of the Japanese troops they faced. One such event took place on August 21, 1942, on the banks of Alligator Creek.

Known by historians as the Battle of Tenaru, the name of the nearby river, it was referred to by some of the soldiers who fought there as the Battle for Hell’s Point.

Fighting for Guadalcanal

On August 7, 1942, Allied forces, mostly American, invaded the island of Guadalcanal. Part of the Solomon Islands, Guadalcanal had been seized by the Japanese as they expanded their empire in the Pacific.

Guadalcanal was strategically significant for several reasons. It was the starting point for a larger offensive, as the Allies fought their way up the west Pacific island chain. Taking it would remove a Japanese threat to Allied shipping in the region. It would also announce to the world that the Americans had arrived, shifting the psychological balance of the war.

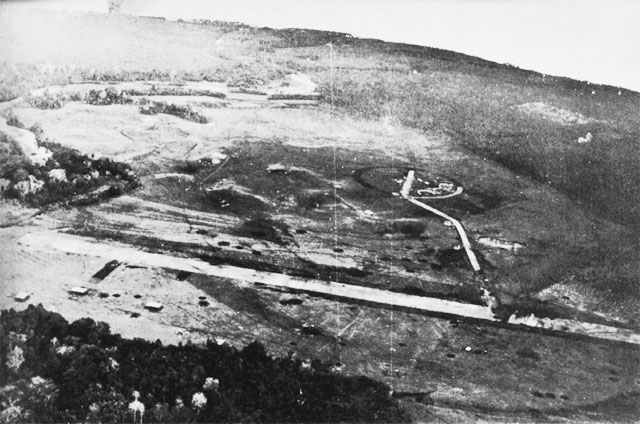

Central to all of it was Henderson Field; an airfield on Guadalcanal.

Build Up to the Battle

Henderson Field was incomplete when the Americans arrived. They rushed to finish it and bring in planes to be based there.

The hastily assembled group of aircraft, known as the Cactus Air Force, gave the Americans a powerful presence in the sky above Guadalcanal. They attacked Japanese ships approaching the island, strafed and bombed enemy troops on the ground, and tackled attacking Japanese planes.

To defend their vital asset, US Marines dug in at many points around Henderson Field, including the banks of the Tenaru River and Alligator Creek.

The Japanese recognized the vital importance of Henderson Field. They rushed troops to retake Guadalcanal, starting with the airfield. The first to arrive were forces from the 28th Infantry Regiment under Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki.

The Japanese underestimated how many Americans were on the island. The Americans learned of their approach. As Ichiki advanced toward Henderson Field, Colonel Clifton B. Cates deployed troops from the 1st Marine Regiment to stop him. Their positions were on the west bank of Alligator Creek, where it flowed into the sea.

First Assault

Just past midnight on August 21, the Marines heard sounds of movement on the opposite bank of the creek. The Japanese had arrived.

Surprised to see so many Americans so far from the airfield, the Japanese initially withdrew. Then at 0130, they attacked. Machine-guns and mortars opened fire on the Americans. 100 Japanese soldiers charged across a sandbar toward the west bank.

The fighting lasted about an hour. American canister shot and machine-guns devastated the advancing Japanese. A few of them got across and seized forward American positions in hand-to-hand fighting. Then a reserve company of Marines attacked, wiping out the Japanese forces on the west bank.

Second Assault and Bombardment

Shortly after, Ichiki launched another attack. 150 to 200 Japanese soldiers advanced across the creek, again making use of the sandbar. The result was much the same as the first time. The defenders’ firepower smashed the exposed attackers. The assault force was almost entirely wiped out.

A surviving officer advised Ichiki to retreat, but he would not.

As the Japanese regrouped, both sides spent the next few hours bombarding each other. American mortars and artillery answered Japanese mortar attacks.

The Third Wave

Ichiki was unwilling to give up, but he was not foolish enough to think that further attacks across the sandbar might work. He looked for another way to attack.

His solution was a flanking movement. He could not go left into the jungle, as there would be more American forces there. Instead, he decided to go right, into the sea.

Around 0500, Japanese troops advanced into the surf. They crossed the mouth of Alligator Creek and came up the beach on the west bank, toward the American positions.

Their path might have been different from the previous attacks, but the results were the same. The Marines opened fire with machine-guns and artillery. The Japanese were out in the open, exposed to enemy fire. They took terrible losses and retreated to the east bank.

With Ichiki still unwilling to withdraw, the two sides faced each other across Alligator Creek. They fired at each other from close range with rifles, mortars, and machine-guns.

Counterattack

As dawn rose, the Americans conferred on how best to tackle the Japanese. They had the advantage of numbers and equipment, and they were going to use them.

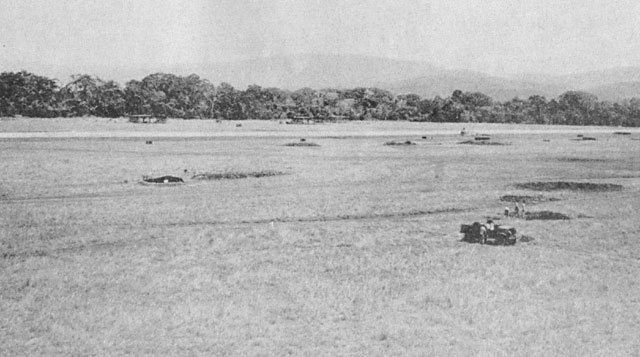

A battalion of Marines crossed Alligator Creek upstream from the fighting. Advancing through the jungle, they approached the Japanese forces from the south and east, cutting off their line of retreat and containing them in an ever-shrinking patch of land around a coconut grove.

The Japanese continued to fight, their backs against the sea. Aircraft from Henderson Field strafed their positions. The Marines brought forward five M3 Stuart tanks, which advanced across the sandbar into the Japanese formations. It was a day of intense fighting.

By 1700 it was over. The Japanese had been crushed.

Aftermath

Colonel Ichiki died in that coconut grove by Alligator Creek, either in the fighting or by committing suicide.

Many of his wounded troops refused to surrender. While lying injured they shot at the Marines who walked among them. The Marines ended up shooting and bayoneting bodies on the ground. Only around 15 injured Japanese soldiers were captured. Approximately 30 Japanese troops escaped from a force of hundreds.

The battle proved that the feared Japanese armies were not invincible. It was a good omen for the Allied troops on Guadalcanal.

Source:

Hugh Ambrose (2010), The Pacific

Nigel Cawthorne (2004), Turning the Tide: Decisive Battles of the Second World War