In the summer of 1942, things were looking bleak for British and Commonwealth soldiers fighting in North Africa. The forces of Nazi Germany under General Erwin Rommel had driven them back from one defensive line to another. This was the one theater of World War Two where Britain had any hope of pushing back the Axis powers. Somewhere in the desert, her armies had to make a stand or let the world be swallowed by darkness.

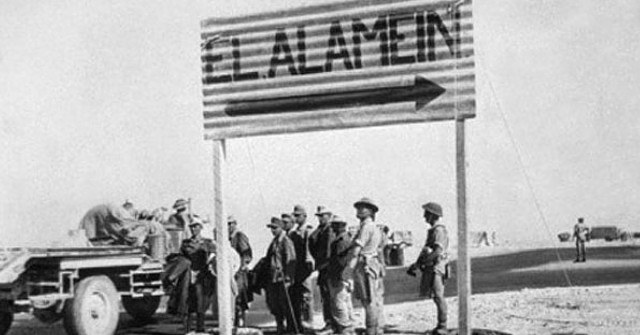

That place was El Alamein.

The El Alamein Line

In late June, the British under General Sir Claude Auchinleck were driven back east in a series of brutal skirmishes. At last, they stopped at El Alamein, 60 miles from Alexandria in Egypt.

El Alamein offered one key advantage for the British that they had not had when trying to form previous lines. Whereas those previous positions had been exposed to a flanking maneuver from the south, at El Alamein that flank could be placed against the Qattara Depression, thousands of miles of marshes and salt lakes through which heavy military vehicles could not pass.

Here, the Australian “desert rats” of Tobruk, along with troops from Britain, India, New Zealand, and South Africa, prepared to make their stand, backed by the Royal Air Force (RAF).

Hitting this line on 30 June, Rommel’s troops found their advance halted. Exhausted and at the end of their supply lines, they regrouped ready for a new push.

The First Battle of El Alamein

On 13 July, Rommel launched the attack that would become the First Battle of El Alamein.

Despite their preparations, the German Panzers were again unable to break through. A counter-attack that night by Indian and New Zealand troops defeated two Italian divisions.

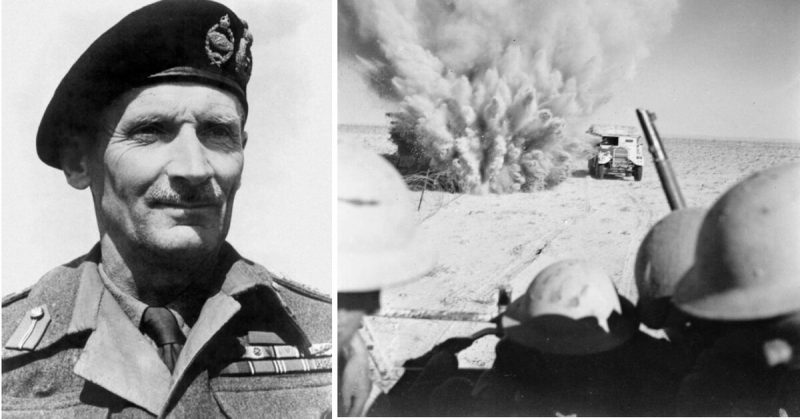

The battle became one of attrition, in which shorter supply lines gave the British an edge. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill went out to visit on the 4th of August, eager to see the Allies go on the offensive. Unhappy with Auchinleck’s cautious approach, he replaced him with Sir Harold Alexander as Commander-in-Chief and General Bernard Montgomery as commander of the Eighth Army.

Rommel Stalls

Trouble with fuel supplies delayed Rommel’s next advance until the 31st of August. This gave Montgomery time to prepare and ruined any chance of surprise. When the German and Italian tanks began their advance they found themselves bombarded by the RAF, while heavy fire hit the infantry clearing mines ahead of them.

A combination of tenacious opponents and soft sands thwarted repeated Panzer offensives in late August and early September. By the 3rd of September, the Axis forces were in retreat. Montgomery, believing his army unready for a pursuit, broke off the battle on the 7th of September.

The two armies sat, facing each other across the sands of El Alamein.

Montgomery’s Plan

On taking over the Eighth Army, Montgomery had immediately reorganized it to suit his way of fighting, a way very different from the cautious Auchinleck. Now he developed a daring, cunning plan.

The conventional view of how to fight in the desert had two key elements – attacking on the southern flank to turn the enemy and focusing on breaking the opposing tanks first. Montgomery threw both these elements out the window in hopes of surprising Rommel.

Dummy supplies, tanks, and radio signals filled the southern end of the Allied lines, tricking the Germans into expecting an attack there. While the RAF bombarded Luftwaffe airfields to keep their planes on the ground, Allied infantry dug concealed trenches towards the German lines further north. When the time came, they would pour out of these trenches, face the Germans in brutal close combat, and break a hole in the line through which the armor could pour.

The Second Battle of El Alamein

On the night of the 23rd of October, Montgomery made his move. As artillery pounded the German positions, soldiers cleared enemy minefields by the light of the full moon. The infantry sprang from their trenches and attacked the Germans. Battle was begun.

The attack was initially successful, but not as decisive as Montgomery hoped. Some troops became isolated, caught out amid the minefields.

Several days of muddled fighting followed, opposing lines becoming tangled in a series of attacks and counter-attacks. Slowly, unsteadily, through the grind of combat, the Allies continued to advance.

Breakthroughs

On the 28th of October, Australian forces began an advance along the coast at the northern end of the battle. On the 30th, they came out of their trenches for an attack that Rommel thought would exhaust them and allow him to cut off a chunk of the enemy. Victory was in sight, and he prepared to take advantage.

It was a trick. At one in the morning on the 2nd of November, Montgomery’s real strike began. Two British infantry brigades and one of armor poured through the lines held by New Zealanders further south. Running full tilt across minefields into the face of the German guns, they took horrific casualties to achieve a critical success. A corridor was punched straight into the Axis lines, and through it poured the British 1st Armoured Division.

No Retreat

Rommel tried to counter-attack with his tanks, but they were halted by bombardments from artillery and aircraft. Orders from Hitler forbade him to retreat, but the enemy was streaming through. To hold the line was suicide, but so was disobeying the Fuhrer’s orders.

Seeing no way out, Rommel turned a blind eye as his subordinates began to withdraw. After 12 days of fierce fighting, the whole German army was on the run. Pouring rain on the 7th of November turned the roads into a quagmire, and through the downpour they escaped the British pursuit.

Church Bells Ring in Celebration

In England, the church bells had been silent for years, waiting to ring the alarm if Germany invaded. After El Alamein, Churchill ordered them rung in celebration. The Allies were finally winning in North Africa. They had suffered 13,500 casualties in exchange for 50,000 Germans and Italians dead, wounded or captured. The mighty Rommel was now in retreat.

It was far from the end of the Allies’ difficulties, but it was, as Churchill said, “the end of the beginning”.

Sources:

- Nigel Cawthorne (2004), Turning the Tide: Decisive Battles of the Second World War.