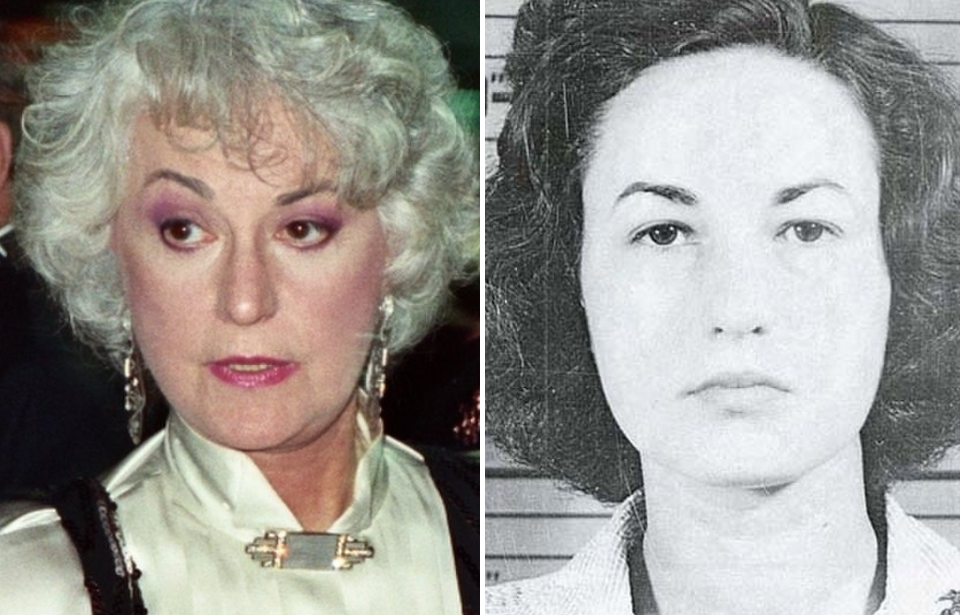

Bea Arthur is a television icon, known for playing the characters of Maude Findlay in All in the Family and Maude, and Dorothy Zbornak in The Golden Girls. However, there’s one aspect of her life you may not be aware of: her service in the US Marine Corps. We didn’t think it possible, but this golden girl just keeps getting cooler!

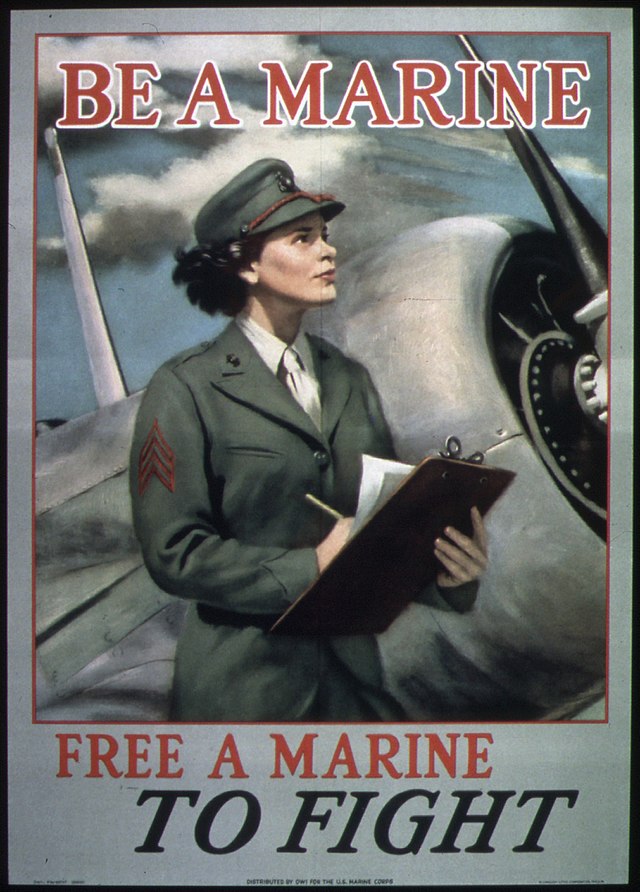

A call to action for all US women

When the United States entered World War II, the government requested that women join the ranks of the military, so male soldiers could join the fight. While the majority of military branches had Women’s Reserves at this time, the Marine Corps did not. This changed on February 13, 1943, when the service released a statement, asking women to “Be a Marine… Free a Marine to Fight.”

While the move was met with some reservations from within the Marine Corps, it was positively received by the public. Many dubbed the new female recruits “Glamarines” and “Femarines,” and overall more than 20,000 earned the title of Marine by the end of the war.

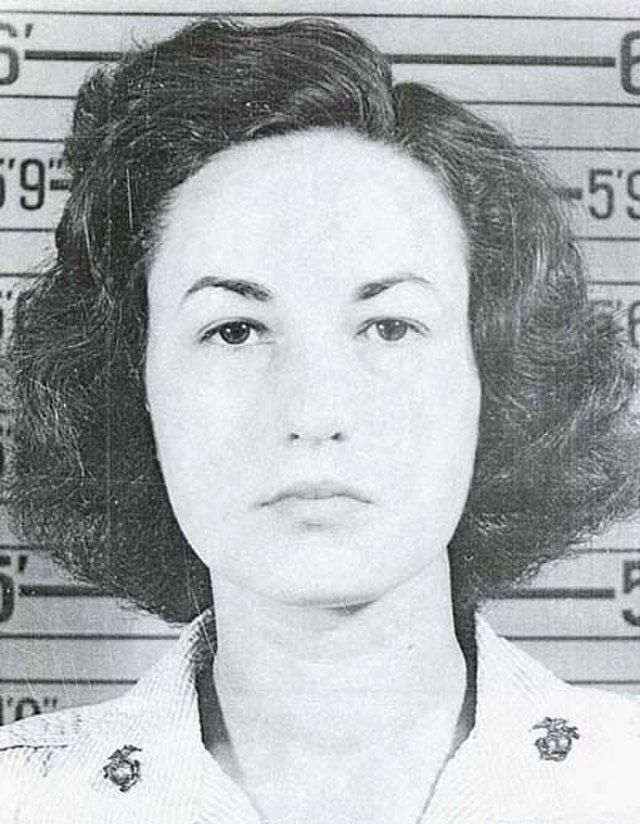

Before television, Bea Arthur was a reservist

With her parents’ permission, Bea, then known as Bernice Frankel, enlisted. The process included physical exams, personality appraisals and recommendations. As the Women’s Reservists section was so new, the Marine Corps had yet to create dedicated forms. This meant recruiting was done using US Navy paperwork.

Bea submitted a handwritten letter, showcasing her dedication to the cause, “I was supposed to start work yesterday, but heard last week that enlistments for women in the Marines were open, so decided the only thing to do was join.” While she hoped to be assigned to ground aviation, she was “willing to get in now and do whatever is desired of me until such time as ground schools are organized.”

On February 20, 1943, Bea Arthur joined the ranks as Pvt. Frankel.

A worthy military career

Bea Arthur attended the first Women’s Reservists school at Hunter College in New York for basic training. She was then sent to the Marine headquarters in Washington, DC, where she worked as a typist. Feeling her past experience would be more valuable elsewhere, she requested a transfer to the Motor Transport School at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. The request was granted in June 1943.

A year into her enlistment, Bea married fellow Marine, Pvt. Robert Aurthur. She adopted his surname, requesting it appear on all official military documents. She kept this name after the couple divorced, altering it slightly into her now-famous stage name.

Between 1944-45, Bea served at the US Marine Corps Air Station (USMCAS) in Cherry Point, North Carolina. While there, she worked as a driver and dispatcher. According to records, she received just one misconduct report during this time, in late 1944. She’d contracted a venereal disease, which left her “incapacitated for duty” for five weeks. The resulting punishment was a dock in pay for that length of time.

At the end of the war in September 1945, Bea was honorably discharged. By the end of her service, she’d reached the rank of staff sergeant.

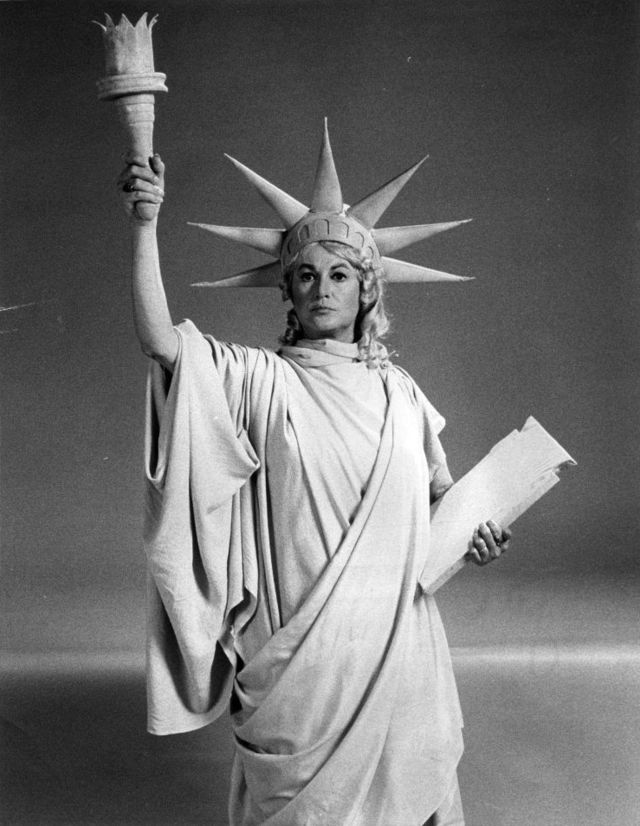

An embodiment of her Golden Girls character

One thing Bea Arthur’s Official Military Personnel File (OMPF) taught us is she was the embodiment of Dorothy Zbornak. Her superiors noted she showed “meticulous good taste,” and was known for being “over aggressive” and “argumentative” – not unlike her Golden Girls character!

Her file also states she was “officious – but probably a good worker if she has her own way!”

Bea Arthur kept the past in the past

Bea Arthur moved on to have a successful and enduring career both on stage and the small screen. After her service, she attended drama school in New York, and eventually landed guest roles on TV. Her big break came when she appeared as Maude Findlay on All in the Family. The role landed its own spin-off show, which ran for six years. She later went on to star in The Golden Girls from 1985-93, securing her status as a television icon.

More from us: The Zimmermann Telegram: Why The US Joined The Allied Powers

Despite her eagerness to serve, Bea largely kept her military service a secret. When asked about the topic during a 2001 interview with The Television Academy Foundation, she denied having ever served, saying, “Oh, no. No.”

It wasn’t until 2010, a year after her death from lung cancer, that Bea Arthur’s OMPF became public record and the true extent of her service was known.