Journalism and war have gone hand in hand for many years, with the field truly coming into its own during the Second World War. On all fronts, journalists worked among the troops, allowing them to report back to their respective publications as events happened.

Most of these men would receive permission from the War Department before going overseas in uniform. Despite this, they weren’t considered combatants and couldn’t carry weapons – not that this mitigated the risk. Many were killed, injured or even captured by their enemies. Most war correspondents worked for print media or radio. However, Bill Mauldin took an entirely different approach, focusing on the creation of cartoons in wartime.

Discover the interesting life of this Pulitzer Prize winner.

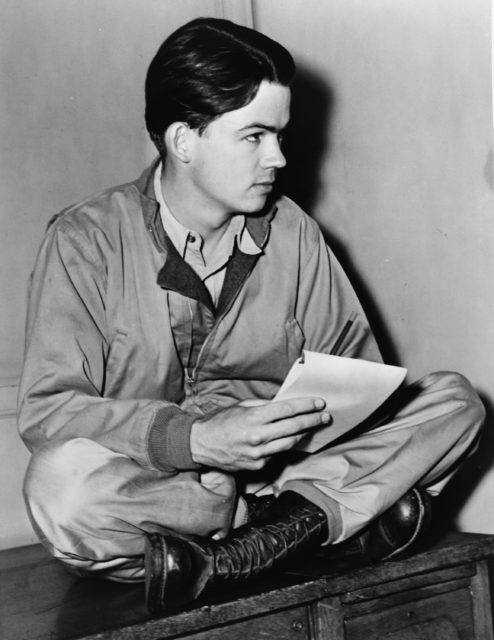

Bill Mauldin’s early life

William “Bill” Mauldin was born in Mountain Park, New Mexico in 1921 to a family with a storied military history. His father had served as an artilleryman during the First World War, and his grandfather had been a civilian scout in the Apache Wars.

Two years prior to the start of World War II, Mauldin’s parents divorced, after which he and his brother moved to Phoenix, Arizona. The pair attended Phoenix Union High School, where Mauldin worked as a journalist for its paper, the Coyote Journal. Deciding his future lay elsewhere, he didn’t graduate. Rather, he began taking courses at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, studying political cartooning.

Involvement in the Second World War

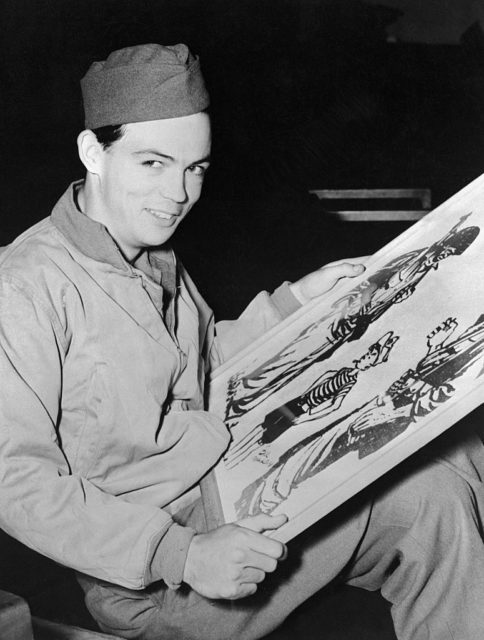

Bill Mauldin continued his work in journalism when he enlisted with the Arizona National Guard in 1940, volunteering with the 45th Infantry Division’s newspaper. It was during these early years with the 45th that he created his two most famous characters: Willie and Joe. They represented two stereotypical American infantrymen serving overseas.

In July 1943, Mauldin was deployed to Europe as a sergeant with the 45th’s press corps, landing during the Allied invasion of Sicily, before pushing into Italy. He was injured during the fighting that occurred in Salerno.

Mauldin worked for both the 45th Division News and Stars and Stripes, the American soldiers’ newspaper, and was transferred to the latter full-time in February 1944. Although his cartoons were already extremely popular with troops and the public at this point, they became even more so after he was pushed to syndicate them and get an agent.

This move was supported by the War Office, as officials thought the cartoons showed a fair and just depiction of the conflict. Mauldin was eventually given significant freedom on the frontlines, getting a Jeep of his own, which he adapted into a traveling art studio. On his travels through Italy, France and Germany, he came face to face with the harsh realities of war.

How did the public receive Bill Mauldin’s cartoons?

Although his cartoons were extremely popular, there was certainly no love lost between Bill Mauldin and many of the American officers. In particular, Gen. George Patton had a distaste for the cartoonist, who’d once commented on the ridiculousness of his decree that his soldiers be clean shaven, even in combat.

Patton said Mauldin ought to be fired for his work, and on one occasion threatened to throw him in jail. Clearly, the cartoonist was unfazed. He later said of Patton, “Oh, sure, that stupid b*****d was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn’t like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes.”

Nonetheless, the opinions that mattered were those of the soldiers whom Mauldin targeted with his cartoons. They thought what he was doing was incredibly admirable, as his work was brutal and honest, and helped them through the war. Given his impact, Mauldin was eventually awarded the Legion of Merit.

Two-time Pulitzer Prize winner

Bill Mauldin was awarded the Pulitzer Prize not once, but twice. The first was in 1945 for the work he published during the Second World War. Highlighted was the drawing of American infantrymen pushing through the rain with a caption that read, “Fresh, spirited American troops, flushed with victory, are bringing in thousands of hungry, ragged, battle-weary prisoners.”

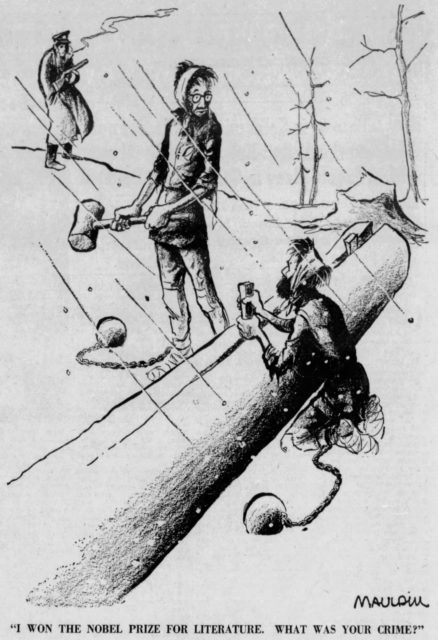

His second Pulitzer Prize came in 1959 for his cartoon commentary on the Soviet government’s treatment of citizens, specifically that of Nobel Prize winner Boris Pasternak, who wasn’t allowed to travel to Sweden to accept his award. He published a cartoon showing the author working as a prisoner alongside another man, with a caption reading, “I won the Nobel Prize for literature. What was your crime?”

Bill Mauldin’s life after the war

Bill Mauldin continued to draw after WWII came to an end. He turned to producing more political cartoons and working as a freelance writer for a variety of publications. In a strange turn of careers, he also starred in two films, The Red Badge of Courage (1951) and Teresa (1951), and even ran as the Democratic candidate for New York’s 28th congressional district in 1956. Unfortunately, his bid was unsuccessful.

While working for the Chicago Sun-Times in 1963, following the assassination of US President John F. Kennedy, Mauldin published one of his most famous works. It was the Lincoln Memorial sitting with his head in his hands.

Mauldin stayed with the Sun-Times until his retirement, which was a touching event. He was honorarily promoted to the rank of first sergeant and given a book of personal notes and letters from various people of importance. He even received a note from Army Chief of Staff Eric K. Shinseki.

The legacy Bill Mauldin left behind

Bill Mauldin died on January 22, 2003 at the age of 81 from complications of Alzheimer’s disease and getting scalded by bathtub water. As with most American troops, he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. He left behind an incredible legacy, and was honored in many ways following his passing.

More from us: Ernest Borgnine: The ‘McHale’s Navy’ Star’s Service During World War II

In 2000, Mauldin was inducted into the Oklahoma Military Hall of Fame and later added to the Oklahoma Cartoonists Hall of Fame. In 2010, the US Postal Service created a stamp in his honor, featuring him alongside his characters, Joe and Willie. Perhaps above all else, Mauldin left behind a legacy of over 1,500 cartoons, which are remembered for the way they encapsulated the experiences of those who served in the Second World War and the political climate of the mid-20th century.