Today, they are one of the most famous military formations in the world. In November 1942, however, the US Rangers were a new and untested unit, preparing for their first experience of war.

Making the Rangers

By the fall of 1942, British commandos had already made a name for themselves fighting in North Africa. Daring raids against German targets had earned them a reputation for boldness. They had also proven the value of such elite specialists carrying out irregular operations in a modern war.

The Rangers were founded on the commando model. Made up of volunteers from the 34th Infantry Division and the 1st Armored Division, they trained under British commandos in preparation for their first operation. With the invasion of North Africa impending, the training was necessarily brief, but it was also rigorous. Less than five months after being activated, the 575-man 1st Ranger Battalion went into action.

The Men Who Joined

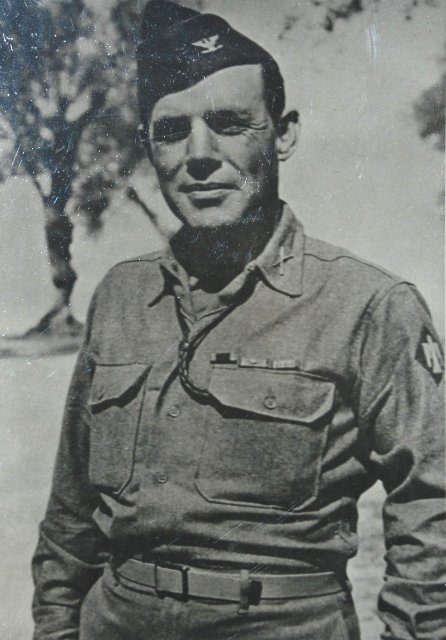

The Rangers were led by Major William O. Darby. A 31-year-old from Arkansas, he was career military. He had graduated from West Point in 1933 and had spent most of his career based at Fort Bliss in Texas, as part of America’s only remaining horse artillery unit.

Accompanying Darby was his executive officer, Major Herman Dammer. Under them were over 500 men who had volunteered to join the Rangers. Each man had his own motives for the move, from patriotism to boredom to the challenge of something new. The case of Carl Lehmann is a reminder of the unusual circumstances in which the unit was formed.

A factory worker from Baltimore, Lehmann felt out of place among the Iowa men whose unit he had been conscripted into. Coming from neighboring towns, they knew each other and shared a background, while he was an outsider. To Lehmann, a man who would never normally have even entered the military, the Rangers were a chance to leave a unit in which he felt out of place. It was a way to make a military life of his own.

Planning for Arzew

The Rangers first saw action during Operation Torch, America’s entry into the European theater of WWII. The Operation was an invasion of Axis-controlled North Africa; far to the west of where the British were fighting the Germans and Italians.

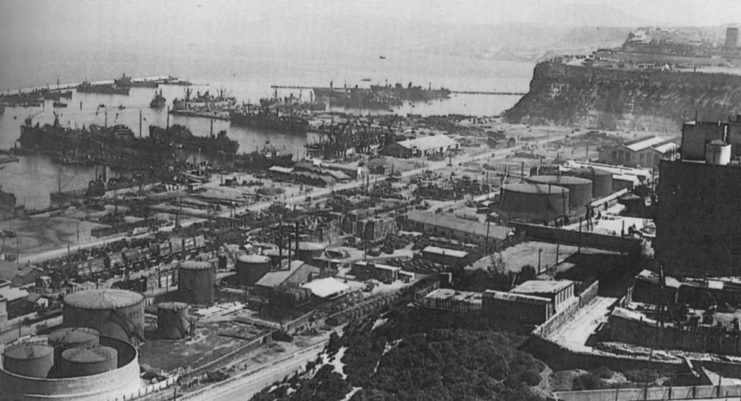

The Rangers were tasked with taking the coastal town of Arzew and the Batterie du Nord, a gun emplacement overlooking the harbor. It was part of the plan to take airfields around Oran. Darby was to land outside the town with two-thirds of the Rangers, march inland, and seize the battery. The remaining men, under Dammer, would land in Arzew and capture Fort de la Point.

They prepared carefully for the attack. The Rangers spent hours with photos and maps, familiarizing themselves with the area. They needed to know it sufficiently to find their way around at night. The officers studied a plaster model of Arzew, working out how best to take it.

The Dock Landing

On the night of November 7, 1942, the attack began.

Major Dammer and his Rangers went ashore in specially adapted boats. They had a ski-like attachment to jump over a cable that crossed the entrance to the port.

Pulling up to the dock, the boats let down their landing ramps. Then the soldiers discovered something their maps and pictures could not show them. The slope up to the dock was covered in slime. They struggled, slipped, and cursed their way into the town.

Fortunately, the Vichy French troops – collaborators with the Nazis – defending Arzew did not notice the Rangers arrival. They crept up to the Fort and cut the barbed wire around it.

A sentry spotted them. He called out, asking who they were. A French-speaking ranger replied, luring the guard down to them. Another man knocked him out from behind.

The Rangers rushed through the gap in the wire and leaped over a wall to get into the Fort. The French put up little resistance, and only a few shots were fired.

In only 15 minutes, Dammer and the Rangers had taken 60 prisoners and the guns of the Fort.

Attacking the Battery

Darby and his men landed unopposed on a beach north of the town, then marched four miles to the guns above. One company set up mortars in a hollow, while others crept up to a deep tangle of barbed wire and began quietly cutting their way through.

Just as they were reaching the last strands, machines guns opened fire on them.

Darby pulled his men back and sent a platoon to destroy a lookout tower. From there, they directed the fire of the mortars, bringing shells down on the French. Almost immediately, the guns stopped firing. The French, believing they were being bombed, had withdrawn to an underground bunker.

The Rangers rushed through the wire and jumped a parapet. One group jammed explosive charges into the muzzles of the emplacement’s heavy guns. Another group fought its way through the battery’s main entrance.

All that remained was the force of French soldiers in the bunker. At first, they refused to surrender. Then the Americans pushed a torpedo down a ventilator shaft and they changed their minds. 60 men surrendered.

It was 4 am. The Rangers first mission had been a success, despite two men killed and eight wounded.

Signal Problems

The final stage in the plan – signaling their success to the forces waiting offshore – was all that was left to do. Unfortunately, their long-range radio had been lost to the sea while loading their boats. So had one of the two sets of colored flares that were the backup signal.

They fired their green flares, but as the white ones were missing the offshore forces did not understand. Two-and-a-half hours later, word finally got through. The first mission of the US Rangers had been a success.

Source:

Orr Kelly (2002), Meeting the Fox: The Allied Invasion of Africa, from Operation Torch to Kasserine Pass to Victory in Tunisia