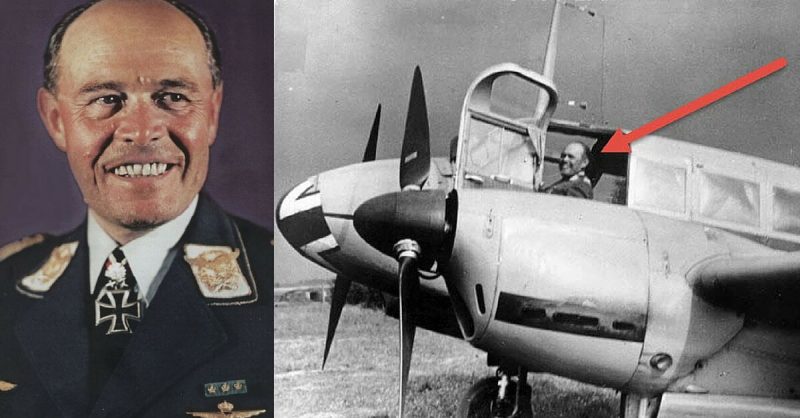

Albert Kesselring, also called “Uncle Albert” by his troops and “Smiling Albert” by Allied forces, was a German Field Marshal (Generalfeldmarschall) and life-long military man. His career spanned over 40 years, three wars, and was equal parts filled with military brilliance, horrific targeting of civilians, and cleaning up, as best anyone could, the messes caused by German tactical errors in World War II.

In his military career before WWII, Kesselring joined the Bavarian Army as an officer cadet in 1904 and served the German Empire when World War I began during which he was promoted to captain, serving in the 1st and 3rd Bavarian Foot Artillery. After the war, he served in various staff positions, helping the German army to reorganize and was eventually promoted to lieutenant Colonel (Oberstleutnant) in 1930.

Though against his wishes, he was discharged from the army in 1933 and appointed to lead the Department of Administration at the Reich Commissariat for Aviation (the precursor to the Reich Air Ministry and the Luftwaffe) and his great aid to the German WWII effort began. He would eventually rise to Chief of Staff of the Luftwaffe and lieutenant general (Generalleutnant) in 1936.

Prior two WWII, Kesselring oversaw the secret development of factories and deals with industrialists and aviation experts to build the German air force into the beast it became. Under his watch, new aircraft like the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and the Junkers Ju 87 (Stuka) were developed and men trained as paratroopers. He also supported the Condor Legion in the Spanish Civil War, made up of German Luftwaffe and Army volunteers fighting for the loyalist side. In 1938, Kesselring was promoted to air general (General der Flieger) and appointed to command Luftflotte 1 in Berlin.

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Kesselring and Luftflotte 1 provided close air support for ground forces and bombed Warsaw heavily. Having his command switched to Luftflotte 2, Kesselring supported the invasions of Holland and Belgium. In Holland, he coordinated assaults between Luftflotte 2, paratroopers, and mechanized forces, and bombed Rotterdam to rubble.

The Battle of the Netherlands was over in four days (May 10th – 14th, 1940). When the eventual push into France lead the German Army to encircle the British Expeditionary force at Dunkirk, General Gerd von Rundstedt ordered the army to halt 15 km away, putting the burden of stopping the evacuation on Kesselring. Kesselring appalled this decision and as his efforts were stalled by bad weather and the British Royal Air Force, over 300,000 Allied troops escaped across the Channel to Britain.

After Hermann Göring’s failed strategy in the Battle of Britain, Kesselring and Luftflotte 2 were transferred back to the East just in time for Operation Barbarossa—the invasion of Russia on June 22nd 1941. Like the invasion of Poland and the Western campaign, Kesselring operated mostly in support of General Fedor von Bock, who was now in charge of Army Group Centre.

With a fleet of over 1,000 aircraft, Kesselring decimated the Russians in the air and on the ground. In the first week of the campaign, he reported that Luftflotte 2 had destroyed over 2,500 Russian aircraft. Through improving army-air coordination and convincing ground commanders to let him focus support on critical points, Kesselring destroyed hundreds of tanks and artillery and thousands of vehicles in the Russian army.

Like how any invasion of Russia goes, Luftflotte 2’s progress was eventually halted over Moscow by winter conditions, but also by heavy air and ground resistance.

Near the end of 1941, Kesselring was moved again, this time to the Mediterranean Theatre as Commander-in-Chief South. Here, he entered the unique position of a former Luftwaffe commander now leading air, naval, and ground forces and reporting only to the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, the German high command.

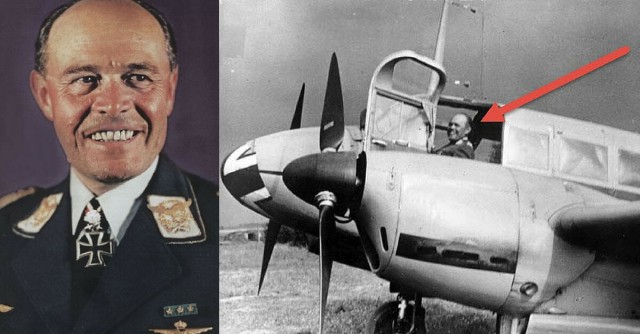

Although, his leadership didn’t stretch terribly far at first as Italy retained direct command of their own forces and many German units, and Erwin Rommel still held command of his Afrika Korps in Libya. Kesselring focused his efforts on gaining air superiority and stifling the British in Malta to increase the flow of supplies to Rommel and thus significantly increased the German effort in Africa.

From this point onward, Kesselring seems to have been mostly responsible for Rommel’s failures. He saw Rommel as unfit for higher levels of command. Mass airstrikes called in by Kesselring helped push back the British forces, which sustained heavy losses, after Rommel split his forces and almost lost half completely when General Ludwig Crüwell was taken prisoner at the Battle of Gazala.

Though Kesselring pushed for the capture of Malta with Operation Herkules, Hilter sided with Rommel in support of an invasion of Egypt. This proved disastrous and the Allies strengthened their position in the Mediterranean.

In October 1942, Hilter gave Kesselring command of all German forces in the Mediterranean except Rommel’s German-Italian Panzer Army. When the Allies then invaded French North Africa in November, Kesselring ordered the defense of Tunisia and a Westward push that ultimately stopped the final phase of General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Operation Torch.

The result was a much prolonged Allied campaign in North Africa and Kesselring managed to stall the inevitable collapse of Tunisia until April 1943. His obstinance also lead to the delay of the Allied invasion of France for most of a year.

For the remainder of the War, Kesselring mostly staged a slow, tactical retreat through Italy. Though his tactics in this no-win scenario were highly praised by Hitler, and even Allied commanders, his time in Italy was marred by the enslavement of Jews for forced labor and massacres of Italian citizens in response to partisan attacks, like the Ardeatine Massacre in which 335 civilians were killed.

Though eventually condemned to death after the war for these massacres, it was Kesselring’s tactical brilliance that lead many British officers and military historians to plead on his behalf and his sentence was commuted. He remained in prison until he was pardoned in 1952. Before his death in 1960, he published his memoirs and contributed significantly to the chronicling of military actions in WWII.

By Colin Fraser