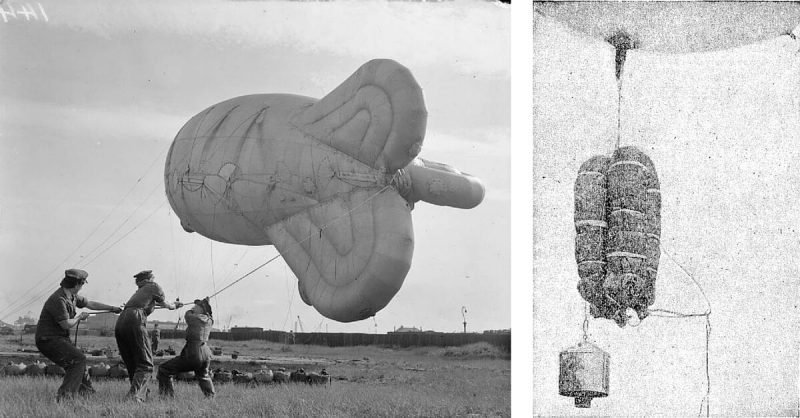

Between 1942 and 1944, the British Royal Air Force and Royal Navy frequently got to bickering over a certain issue. It was, oddly enough, to do with a program pushed by the Royal Navy’s Captain Gerald C. Banister, Director of Boom Defense to use free-flying, eight foot wide, hydrogen-filled balloons to sabotage German infrastructure.

The RAF was often concerned about the balloons interfering with their air operations and rightly so. The German Luftwaffe was endlessly harassed by these simple devices and to the Admiralty and British Chief of Staff, that alone was worth the small cost for deploying these balloons. And the toll on German infrastructure, forests and farmland was greatly more lucrative to the British war effort.

Mind you, there were also some pretty monumental accidents with the program, but for the most part, these relatively cheap, clever and amusing little devices were a delightfully successful tool in the British arsenal. It was Operation Outward.

The lightbulb of this idea first clicked on with the Air Vice Marshal of the Balloon Command, who oversaw barrage balloon operations intended to defend against low-flying Luftwaffe bombers. It was suggested to launch balloons that would fly into German territory using radio trackers and triangulation to follow their course. The idea was initially turned down as, well, silly.

But after a monstrous storm in mid-September 1940, when several barrage balloons came loose, drifted over the North Sea and reaped havoc on electrical infrastructure in Sweden and Denmark, Prime Minister Winston Churchill asked that the strategic value of balloon attacks on Germany be assessed.

The Air Ministry once again deemed the whole idea rather silly and shot it down (so to say). Captain Banister pushed the idea through the Admiralty, however, and after studying the factors carefully, they decided the idea was brilliant.

Here’s what they found: In studying meteorological concerns, they discovered that the winds above 16,000 ft (needed for such devices to float the distance and direction from Britain to Germany) almost always went West to East, meaning the Germans couldn’t retaliate in kind. Also, the whole apparatus of the balloons and their sabotage devices were not only relatively cheap (about £85 at current day equivalent), but could be made almost exclusively with surplus materials.

The rigged-up balloons themselves were designed thoroughly and with great imagination. Inside surplus eight-foot wide latex weather balloons filled with hydrogen, the Navy inserted a wire so that as the balloon rose and continued to expand it would tighten the cable and stop the ascent at 25,000 ft. (7,600 m). They also added a slow-burning fuse that was calibrated, using calculated arrival time over Germany, to activate a slow drip from a can of mineral oil to lighten the balloon’s load and slow its decent.

The same slow-burning fuse was also rigged to the balloons’ weapons. These weapons came in two forms: wires and incendiaries.

Shorting and Igniting

When the fuse triggered the wire apparatus, the balloon would drop a 300 ft (91 m), 1.8mm diameter steel wire at the end of a 700 ft (210 m) hemp cord. The wire would then trail below the balloon until it (with any luck) struck German power lines, shorting out the lines and damaging electrical infrastructure to a great degree. These worked to varying success but certainly succeeded quite frequently.

The incendiary devices came in several forms and were intended to ignite forests and fields. One design was a metal canister which contained seven or eight half-pint bottles filled with white phosphorus, benzene, and a strip of rubber which would melt inside. When the fuse activated the device, it would tip over and drop the bottles which would shatter and ignite.

The second kind of device was simply a metal imperial gallon container filled with jelly that would ignite into a 20 ft fireball.

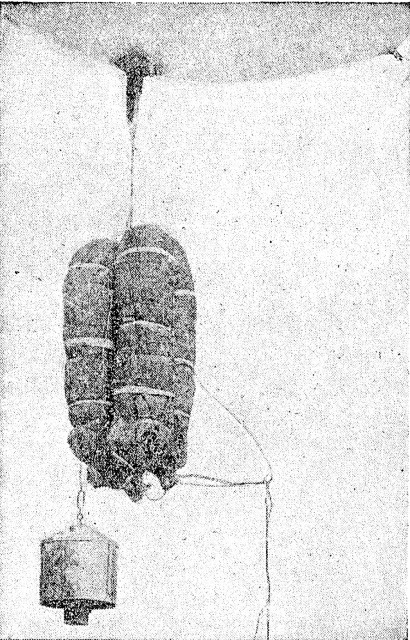

Socks

And then there was the incendiary sock, a tube filled with wood wool and coated in wax which, when dropped, formed a V shape to get it stuck in a tree where it would then burn down over 15 minutes, hopefully catching the forest ablaze. Luckily, the Royal Navy already had about 10,000 of these things just lying around.

The first launch site for Operation Outward was a golf club in Suffolk in Britain’s Southeast. Over 200 officers and non-commissioned men and women from the Royal Marines and Women’s Royal Naval Service, under the command of Boom Defense were responsible for lofting these little gifts to Germany into the air on days with favorable weather. They had to coordinate with the Air Ministry, as well, to avoid damaging British aircraft, which led to the bickering first mentioned.

Between March 20th, 1942 and September 4th, 1944, Operation Outward launched 99,142 balloons, sometimes as much as 1,800 over the course of a few hours.

The results were spectacular, probably bringing cheeky grins to many faces in the Admiralty.

The first indication of success was chatter heard in Luftwaffe communications of German pilots chasing down these devilish balloons. The cost of fuel and wear and tear to their aircraft was already far outweighing the cost the Royal Navy put into the program.

Throughout the remainder of the war, intelligence and various news articles in occupied areas like France and Denmark provided some reports of forest and farm fires and many power outages caused by shorted wires in Germany. The personnel and material needed to attend to these situations were far from negligible.

After the war, a report studying German records concluded the damage done by Operation Outward was, at the very least, £1.5 million worth (or £49 million in 2016). Of course, records were both incomplete and not even available from the Russian occupied zone.

Highs and Lows

Highlights and glaring mistakes from Operation Outward include: when a wire balloon hit an 110,00-volt line near Leipzig, Germany in July 1942 causing a transformer failure at the Böhlen power station which then burned to the ground.

On the other side, one balloon got caught by a wind and headed for England and knocked out power in the town of Ipswich. In a grave incident the night of September 19th, 1944, one balloon drifting over Sweden caused two trains to crash at Laholm.

By Colin Fraser for War History Online