In May 1941, German paratroopers invaded and overran the island of Crete. A British force, which included New Zealanders and supported by the local resistance, fought hard for a week before being forced to evacuate the island.

The British could have done more to preserve Crete but if they had done then far more might have been lost. The sacrifice of Crete and the sacrifices of the men who fought there helped to win the war.

The War in the Mediterranean

During the Second World War, fighting in the Eastern Mediterranean had many facets. Two of the most important were the battles for Greece and North Africa.

At first, the British focused on Greece. They hoped that, by supporting the Greeks, they could halt the Axis advance and then push them back through the Balkans.

It was not to be. The initial invasion of Greece by the Italians was a massive failure. It forced the Germans to intervene, and their more capable military quickly defeated both the Greeks and a British expeditionary force.

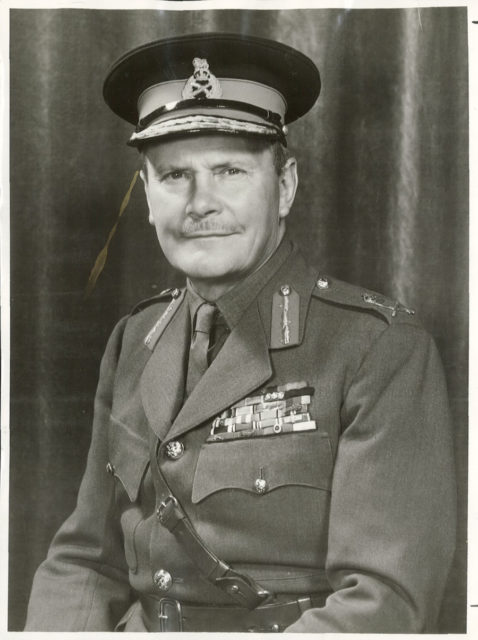

Within a month, only one part of Greece remained free. It was the Island of Crete, defended by a British Army contingent under General Bernard Freyberg, the Commander of the New Zealand Division.

Islands such as Crete were important in controlling the sea lanes, as they provided bases for ships and planes. As such, Crete could be invaluable in maintaining supplies to British troops fighting in North Africa, the only active front now that Greece had fallen. However, it was not the most strategically important of these islands.

Ultra Intelligence

On April 30, 1941, Freyberg had a meeting with his superior, General Wavell. There he was told about a part of the Allied war effort he had never heard of before. It was so secret it would not be discussed openly until decades after the war.

Its name was Ultra.

Ultra was the interception and decryption of high-level German orders, in particular, those encoded using the Enigma machine. It was kept secret so the Germans would not know the code had been cracked, and therefore change it. The Poles had made the first breakthrough, but it was now in the hands of the British, and they were very careful with its use.

If any word of Ultra leaked out, then the single best intelligence source of the war would be lost.

Working in Secret

At that April meeting, Freyberg was told he would receive information from Ultra. It came with rigid conditions. He could not discuss Ultra with his staff. He could not act based on information that came only from Ultra, in case it gave the game away to the Germans. He could use the info to guide him in whatever else he paid attention to, and to help him filter and understand lower level intelligence. Ultra itself must remain secret.

This was how Crete’s sacrifice helped to protect British operations. As word came in of a planned German invasion, Freyberg prepared the best defenses he could without giving away clues about Ultra. It allowed a strong defense to be mounted, but not as strong as if everyone had been acting on Ultra.

The limited resources Wavell gave Freyberg was also due to the other theaters of war. With Greece gone, the British needed to concentrate their efforts in North Africa. Crete would have to get by with what Freyberg already had.

The German Attack

Early on May 20, the German attack began. 500 transport planes and 72 gliders soared over Crete in history’s first great paratrooper invasion. 500 bombers and fighters supported the commandos as they descended on the island.

The initial results were mixed. Freyberg made good use of the limited resources available to him.

Landing around the Máleme airfield, German troops took Tavronitis Bridge and later the airfield. Others landed among the British and Commonwealth forces and suffered heavy casualties. Units were wiped out or scattered across the countryside. Heavy mortars were lost in a reservoir. A glider crash killed a group of divisional commanders.

Fresh German troops arrived the next day, led by the invasion’s Commander, Major-General Ringer. At dawn on the 23rd, he launched a three-pronged attack that quickly began to push the Allies back. Fierce fighting erupted in the north against the Cretan resistance and in the east against troops from New Zealand. It was not enough to save Crete.

On May 27, Freyberg accepted the inevitable. He gave the order to evacuate.

Hitler Loses Faith

Before Crete, paratrooper landings had seemed to hold out great promise to the Germans. Swift, sudden attacks by elite soldiers had brought them victories in the late stages of the First World War. They had brought success in Poland and France at the start of this war. Making such attacks from the air fitted the strategy and self-image of the German military.

Although Crete had fallen, the cost was too high for Hitler. 3,714 men had been killed, and 2,494 wounded – more losses than in the entire Balkan campaign.

The Fuhrer banned further paratrooper invasions. A year later, a prospective airborne invasion of Malta was canceled on these grounds.

Why Malta Mattered

As Rommel charged against the British in Egypt, Malta was one of the few places holding open British supply lines in North Africa. If it had fallen, the whole British operation in the desert could have crumbled. There would have been no foothold for the Americans to join, no springboard for the invasion of Italy, no distraction for the Axis as D-Day approached.

The sacrifice of Crete preserved the secrecy of Ultra. It left troops available to fight in North Africa. The intelligent and courageous defense Freyberg and his men put up ensured an end to the threat of German parachute landings.

Great sacrifices were made at Crete. They were vital to the war in North Africa and the Mediterranean.

Sources:

Ralph Bennett (1999), Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the War with Germany 1939-1945.

Nigel Cawthorne (2004), Turning the Tide: Decisive Battles of the Second World War.