During WWII, the Japanese took a calculated risk by invading Singapore with far fewer numbers than the defenders. They adopted devious tactics to secure the city. Singapore was then part of Malaya, which was part of the British Empire. As early as 1936, Lieutenant General Sir William George Shedden Dobbie (the General Officer Commanding of the Malaya Command) was already concerned about Japan’s saber-rattling in the region.

A veteran of the Second Boer War and WWI, he became convinced that a Japanese attack was imminent. So in n May 1938, he demanded reinforcements for “The Fortress” – meaning Singapore, since it was the site of Britain’s naval base.

The British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was more concerned about Europe. Germany was the immediate threat, so Britain’s overseas territories were of secondary importance. This decision would hasten the end of the British Empire, since her colonies were starting to resist their second class status. Churchill’s policy made Australia and New Zealand were especially unhappy at how vulnerable they became, while Malaya would suffer because of the British Prime Minister’s lack of foresight.

The crossroads between Asia and the South Pacific, Singapore was a mixture of indigenous Malays, ethnic Chinese, Indians, and European colonists. Though devoid of natural resources, its strategic value was evident to the Japanese who attacked on 8 February 1942.

The man in command of the invasion was Lieutenant General Tomoyuki Yamashita. He was to engage in a massive bluff to deceive the British. Yamashita’s force had come through northern Malaya, as Dobbie had predicted. But by the time he looked across the Johor Strait toward Singapore, he was left with only 18 tanks and limited fuel.

Many Japanese soldiers had been lost in the swampy jungle with its few roads made muddy by the monsoon season. By the time they were ready to cross over, each of Yamashita’s 30,000 men were reduced to only 100 rounds of ammunition per day.

Called the “Tiger of Malaya” in the Japanese press (and the “Beast of Bataan” by the Americans), Yamashita admitted in his diary that he was afraid. He had bragged that his men could win on only two bowls of rice a day, which was what they did since the British engaged in scorched earth tactics as they retreated back to Singapore.

By the time he made it to the Fortress, he had lost 4,515 men. If Singapore didn’t surrender at once, his invasion was doomed. Yamashita wanted Singapore taken and to be there by February 11 to commemorate the coronation anniversary of Jimmu (660-585 BC), the first emperor and founder of Japan. He failed to achieve his goals.

Yamashita pinned his hopes on intelligence reports which suggested that the Allied forces on the island numbered only 40,000. It was wrong. There were almost 120,000 of them waiting for the Japanese. Unfortunately, the Allies were poorly led, had even worse intelligence, and lacked vital military supplies and equipment because of Churchill.

Still, there was hope. On the evening of February 10, the Japanese were on the Kranji River, but were stopped by the Australian 27th Brigade. Some boats got bogged when low tide hit, and a few sailed into the wrong tributaries. Up on higher ground, the Allies lit fuel tanks and dumped them into the Kranji, setting the water ablaze and burning Japanese troops.

Instead of pressing their advantage, however, the Malaya Command ordered the Australians to retreat. The surviving Japanese were amazed. From that point on, any hope of stopping them ended as more poured in from the Kranji. Further north, the causeway (which had been bombed), was also abandoned, allowing the Japanese entry from two points.

By February 11, the Tengah Airfield was in Japanese hands, but they were desperately low on ammunition. Still bluffing, Yamashita sent Lieutenant General Arthur Ernest Percival (commander of the British Commonwealth forces on Singapore) a letter, urging him to surrender to spare needless death. Percival refused.

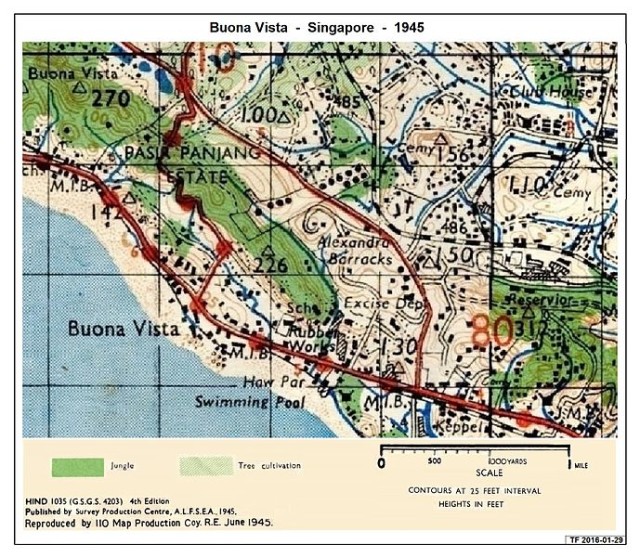

On February 13, the Japanese 18th Division began attacking the southwestern coast along the Pasir Panjang Ridge. Opposing them were the 1st Malay Brigade who held their ground till the next day when the Japanese began using tanks. By 4PM, the Malay Brigade were forced to retreat uphill to Bukit Chundu (Opium Hill) where they made their last stand.

They had to. If the Japanese took the ridge, they would have direct access to the Alexandra area with its military hospital, ammunition and supply depots, as well as other vital installations. They would have had Singapore at their mercy. By that point, however, it was already hopeless for the brave Malays.

C Company, led by Captain HR Rix, was unable to retreat further south because of burning oil in the canal. This separated them from D Company, greatly reducing their numbers. He ordered his men to hold the hill at all costs before he was shot. Command fell to Lieutenant Adnan Saidi, who ordered a retreat further uphill and hold their ground.

Frustrated by this, the Japanese undressed some of their Sikh captives and had 20 men put their uniforms and turbans on. They climbed up the hill and started waving to the defenders, hoping to make a breach through their line so the rest could follow.

But the Japanese made a fatal mistake. British soldiers march in a line of three, but they were approaching C Company in a line of four. As soon as they reached the Malay Brigade, Adnan ordered his men to open fire, killing most before the rest fled back downhill. Despite this, the British forces position had become hopeless.

Hours later, the Japanese overran the hill, overwhelming the brigade. Then they went to the hospital and slaughtered its patients and staff. By February 15, Singapore officially surrendered. if Percival had been a stronger commander Singapore could have held out and the Japanese left in a precarious position.While many European civilians were spared, the Chinese were not. For the Malays and Indians, hell began. The Japanese occupation of Singapore was to last until 1945.

After the war, Yamashita was hung in the Philippines for his many war crimes.