At the outset of the Second World War, the United Kingdom was faced with many problems, one of which was how to train the aircrews who would be crucial to the war effort. The UK was a less than ideal location for training, due to its close proximity to Europe and the high likelihood of an eventual attack on RAF airfields.

Rather than risk the unpredictability of training in the UK, the Royal Air Force put forward a proposal to certain members of the Commonwealth to create the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP).

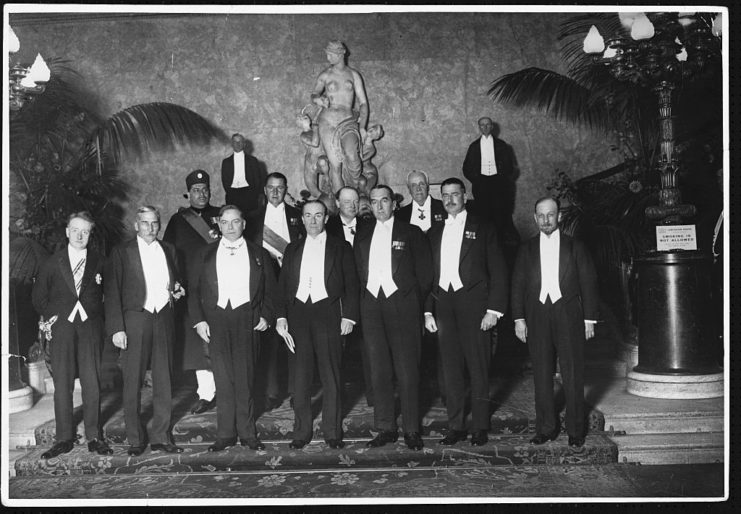

Signing the agreement

Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, the UK’s Arthur Balfour (Lord Riverdale), Sir William Joseph Jordan from New Zealand and Australian Stanley Melbourne Bruce signed an agreement, named for Lord Riverdale, on December 17, 1939 to collectively train Commonwealth air personnel.

The primary intention was to train Commonwealth aircrews in Canada, as the amount of open space was ideal for flight training, as was the weather. There was also little-to-no threat to Canadian airspace from the Luftwaffe or, later in the war, Japanese aircraft. Although much of the training was to take place in Canada, the agreement also established flight schools in British colonies, such as Bermuda, South Africa and Southern Rhodesia.

Mackenzie King also agreed to much of the training taking place in Canada because it meant he could minimize the number of Canadian soldiers serving overseas due to their significant contribution to training air personnel. While other nations also ran training programs, Canada far surpassed them in program size and in the number of personnel trained by the end of the war.

Training in Canada

The intent of the BCATP, when fully developed, was to have 520 pilots with elementary training, 544 with service training, 340 air observers, and 580 wireless operators and air gunners complete it every four weeks. It was a large task for the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) to develop the program at the rate needed to meet these expectations, due to the service’s small size at the outset of World War II.

When the war started, the RCAF had roughly 4,000 personnel, but would need to grow to 10 times that size in staff alone to operate the BCATP.

Based on the proposed BCATP, training schools were established throughout Canada, both on existing airfields and on ones built specifically for the program. There were 231 sites, largely airfields, 80 of which were built by the Canadian government following the signing of the agreement.

Pilots and navigators started off at Initial Training Schools before moving into their own respective training. Navigators moved on to Air Observer School, followed by Bombing and Gunnery School and Navigation School, while pilots attended Elementary Flying Training School before entering Service Flying Training School.

There were also specific schools for wireless training and flight engineers.

Training in the Dominions

Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) personnel were predominantly given basic training in Australia before moving to Canada to complete more advanced training. In the mid-1940s, however, some RAAF trainees were sent to Southern Rhodesia, then a British colony, for this.

Once the war in the Pacific began, most RAAF personnel were no longer sent to other counties for training and, instead, trained solely in Australia before being sent to serve in the Pacific Theater. As with the RAAF aircrews, the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) trained some of their airmen in New Zealand and sent others to Canada to complete further training.

The country whose involvement in the BCATP was arguably least expected was the United States. When the plan was established, the US was still neutral. That didn’t stop the RCAF from recruiting American pilots to cross the border and join up. By the time the US joined the war following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, roughly 6,129 Americans had joined the RCAF.

Notable graduates from Canadian flight training schools

There were a number of BCATP graduates from training schools in Canada who were from outside of the Dominion, as well. These individuals trained as part of the RAF and included aircrews from Poland (448), Norway (677), Belgium and the Netherlands (800), Czechoslovakia (900), and Free France (2,600).

With such a large number moving through the BCATP, there were a fair few flying aces and pilots whose training was completed in Canada. Two notable men were Arthur “Spike” Umbers of the Royal New Zealand Air Force and Joseph “Big Joe” McCarthy, an American serving with the RCAF.

Umbers completed his preliminary flight training in New Zealand before traveling to Canada in 1941. He was trained at the No. 6 Service Flying Training School near Dunnville, Ontario, roughly an hour from Buffalo, New York. During the war, he is credited with destroying upwards of 15 V-1 flying bombs, with some estimates increasing this total to 28, and five other aircraft.

He was killed in action on February 14, 1945, when his plane was hit by flak and crashed. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar for his service, and is buried in the Munster Heath War Cemetery in Germany.

McCarthy traveled across the Canadian border to join the RCAF in May 1941. While he didn’t earn the flying ace status, he participated in 30 air raids over Germany prior to the Dambusters Raid in 1943. He flew in the Avro Lancaster “T-Tommy,” which was tasked with targeting the Sorpe Dam, which it did. However, the dam couldn’t be breached.

He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, the Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar, and the Canadian Forces Decoration for his service.

Notable aircraft used

There were a number of different aircraft used throughout the program, based on the training location and purpose. Those training to be fighter pilots usually flew North American Harvards, while pilots training as bombers or for coastal and transport operations flew Avro Ansons, Cessna AT-17 Bobcats or Airspeed AS. 10 Oxfords.

Bristol Fairchild Bolingbrokes were used for gunnery practice, while Westland Lysanders were used for target towing. The UK provided many of the extra 3,540 aircraft needed for flight training, including de Havilland DH. 82 Tiger Moths, Fleet Finches, Harvards, Avro Ansons and Fairey Battles.

The lasting impact of the BCATP

The BCATP came at a significant cost to the various nations of the Commonwealth. It officially ended on March 31, 1945. By this point, the signatory nations had spent approximately $2.2 billion CAD on the program, $1.6 billion of which was contributed by Canada.

After settling all existing debts between nations, the UK still owed Canada $425 million CAD of promised contributions. Canadian Parliament canceled the UK’s debt in May 1946, which escalated Canada’s financial contribution to 92 percent of the BCATP’s total operating costs.

More from us: The Five Greatest Aircraft Ever Flown By the US Military

The program was immensely successful, with over half of the Commonwealth air force being trained through the BCATP. By the end of the war, 131,553 airmen had graduated from the schools in Canada, including over 50,000 pilots. The remaining students were made up of flight engineers, bomb aimers, navigators, gunners and wireless operators.

The BCATP was heavily praised by Allied leaders. US President Franklin D. Roosevelt stated that the British Commonwealth Air Training Program had turned Canada into the world’s “aerodrome of democracy.” British Prime Minister Winston Churchill thought the BCATP was Canada’s single greatest contribution to the Second World War.