Like other European nations, the British discovered the value of photo-reconnaissance (PR) during the First World War. Seeing a new way to learn about the enemies armies, they began photographing them from the air. Specialists on the ground then interpreted the results. Innovators such as John Moore-Brabazon and Victor Laws made ground-breaking developments in equipment, techniques, and training.

By the start of the Second World War, another transformation in PR was needed.

A Neglected Art

Like most of the British military intelligence, PR was neglected between the wars. The War Office retained control of photo-interpretation (PI) work but refused to invest in the new equipment it needed. There was only one fully qualified PI officer working at the War Office in 1939, and only two were sent to France with the first wave of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). Lord Hankey, writing a government memorandum on home defense in May 1940, did not recognize how under-equipped PR was.

Remarkably, this left Britain as one of the better-equipped nations. The American army had no PR officers when it joined the war two years later.

Winterbotham and Cotton

PR was revitalized by the work of two men – Frederick Winterbotham and Sidney Cotton. Winterbotham, a First World War PR pioneer, was now the senior air officer in the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). Finding the British uninterested in PR, he worked with the French in early 1939. They arranged PR flights piloted by Cotton, an Australian flyer, over Germany. The results revealed what could be achieved and got the British interested.

Steps to Improve

Huge improvements had to be made if PR was to be effective.

PR specialists were recruited and trained. Even before the BEF left the continent, this was happening.

Specialist equipment was needed. To carry out PR flights without being caught, pilots needed to fly quickly and at high altitude. It meant using the latest planes and improved lenses.

Finding the equipment became easier once the Royal Air Force (RAF) took overall control of PR. In a change from the separate intelligence gathering of Britain’s military arms, the RAF carried out PR for itself, the army, and the navy.

Coordination, men, and resources improved PR work.

The Bismarck and the Tirpitz

One of the main motivators to improve PR was German work on two new battleships. The Bismarck and the Tirpitz would be the largest battleships in the world. As such, they would be a huge threat to Britain’s maritime supply lines.

Admiral Godfrey, the head of naval intelligence, encouraged the use of PR in finding these ships. It led to the swift identification of the Tirpitz. It also showed how important the right tools could be, as a Spitfire with extra fuel tanks got photos other planes could not.

Additionally, it demonstrated how important context and interpretation were. Clues to the Tirpitz’s imminent departure were not understood because there were no photos of its dock from earlier dates.

Dunkirk to Taranto

Following the fall of France, Britain was cut off from many sources of intelligence. PR became particularly important and received the resources appropriate for this. Together with signals intelligence, it helped to monitor German U-boat production and shape the Battle of the Atlantic.

November 11, 1940, brought a notable triumph for PR. The aerial attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto was made successful by intelligence. Photos taken hours before the assault showed where the Italian ships were, allowing brave pilots to launch an accurate and surprising attack. Half the Italian fleet was put out of action.

Monitoring Sealion

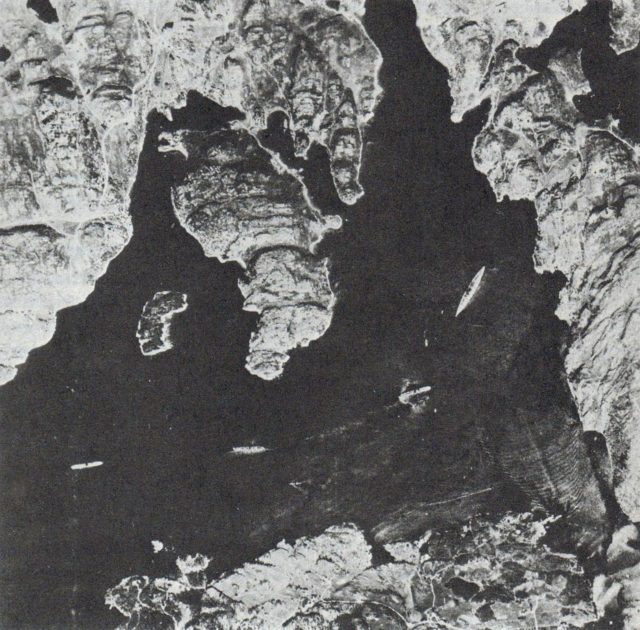

In the second half of 1940, British PR officers undertook one of their largest operations. Sending many flights across the Channel they monitored German-controlled ports, recording the preparations for Operation Sealion, Hitler’s planned invasion of Britain.

Although the operation was eventually abandoned, the work observing it was invaluable. Throughout, the British had a good idea of where an invasion would come from and how large it would be. PR provided the first clues that the attack had been called off, as traffic grew thinner around the ports.

Official Resistance

Despite this, there was still resistance at the highest levels to PR. Nowhere was this more toxic than at Bomber Command.

Those in charge of Britain’s bombing campaign were convinced their work was both accurate and effective. In reality, many bombs were falling wide of the mark and doing little damage. The Germans were aware of this, as were neutral observers. Bomber Command refused to believe it.

PR showed how little effect the bombs were having compared with Bomber Command’s claims. Rather than accept their limitations, they continued to reject the evidence, becoming increasingly hostile to a useful source of intelligence.

Specialists and International Cooperation

In 1942, the Americans joined the British PR center at Medmenham. Working together rather than answering to their separate chains of command, the British and Americans exchanged knowledge and ideas. It quickly led to improvements in areas such as the understanding of bomb damage.

Increasingly specialized knowledge allowed the Allies to understand the photos thoroughly. By 1942, PR had become a sophisticated and varied business.

The Limits of PR

PR had become one of the most useful tools in British military intelligence, but it had its limits.

It could show where buildings were but not what was inside them. It could show vehicles but not their state of repair and supply. It could show the movement of troops, but not their morale or orders. In cloudy weather, PR could not take place.

It was therefore at its most useful when combined with other intelligence. As work in the other areas improved, so did PR’s use. The staff working in PR had brought it a long way by themselves. Britain would never be flying blind again.

Sources:

Ralph Bennett (1999), Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the War with Germany 1939-1945.

Taylor Downing (2014), Secret Warriors: Key Scientists, Code Breakers, and Propagandists of the Great War.