At the outbreak of the Second World War, much of the British military were not equipped for dealing with military intelligence. The exception was the Royal Navy. It proved to be the most capable branch to analyze and act on the information provided. Unfortunately, it was also the part of the military with the least information with which to work.

Building Up OIC

The heart of naval intelligence was the Operational Intelligence Centre (OIC). It was the creation of Admiral James, Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff from 1936.

James had experience of the value of intelligence. In 1917-18 he had been head of Room 40, the Navy’s team decrypting German signals.

From the mid-1930s onward, James saw that a variety of military intelligence was coming to the Navy. Information about the Italian invasion of Abyssinia and the Spanish Civil War had value both as an insight into those wars and as a sign of German and Italian preparations for war.

The Naval Intelligence Division (NID) lacked the experience and manpower to deal with the data. It needed to be analyzed and forwarded to the relevant parts of the military. A team was necessary to decrypt and analyze data, as well as explain its significance to senior officers.

The OIC was established as a small specialist department. By 1939, under the command of Lieutenant-Commander Norman Denning, the OIC had 50 staff. At the time of the Munich conference, their tracking of the battleship Deutschland and analysis of its movements indicated Germany was not yet priming for all-out war.

Skilled Specialists

Naval intelligence recruited highly skilled people from both the military and civilian worlds. Ian Fleming, the future author of James Bond, was behind a unit that collected military intelligence in active combat zones. Barrister Ewen Montagu was one of the men behind Operation Mincemeat, the plan that deceived the Germans about the invasion of Italy.

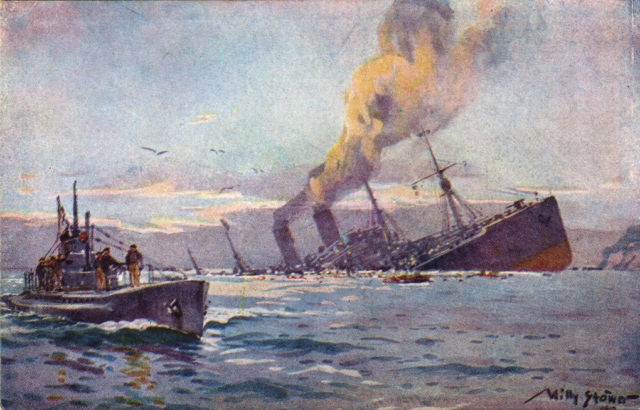

Some of the most capable operatives were in the Submarine Tracking Room. There, Rodger Winn and his deputy Patrick Beesly ran one of the most important operations of the war. Using a variety of information, they worked out the movements of U-boats and redirected convoys out of their path, enabling people and supplies to cross the Atlantic safely.

When attacks started coming off the American coast, Winn traveled to America to offer them his expertise, shaping anti-submarine intelligence on both sides of the ocean.

Stops and Starts in Enigma

Skilled and well-supported as OIC might have been, they often lacked the material they needed to understand German movements.

The problem was well illustrated in the spring of 1940. British intelligence cracked what it referred to as the yellow key, the code used for many German transmissions during the invasion of Norway.

Anticipating a flood of new intelligence, the Admiralty told the Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet to be ready. However, the code was being used by the German army and its air support, not their navy. Any nautical information the British gained from it was incidental.

Ultra, the high-level intelligence acquired by cracking the German Enigma code, was of varying value. There were times when OIC, with its skilled cryptographers and analysts, was privy to high-level orders sent out to enemy submarine commanders in the Atlantic. At these times, Winn and his team were at their best, able to save many lives and vital supplies.

On other occasions, the codes changed, and they were left in the dark. For ten dangerous months, they lacked access to the critical submarine signals and had to fall back on other sources.

Lacking What the Air Force Had

It was a cruel irony that the tools which would have been most valuable to Naval intelligence were at first limited to the Royal Air Force (RAF).

Radar was a vital intelligence tool in the air war. It allowed incoming planes to be detected, giving pilots time to mobilize against attacks. However, it took years for similar technology to detect submarines surfacing in the waters of the Atlantic.

In aerial reconnaissance, the problem was resources, not technology. Photographic reconnaissance was one of the most valuable tools in Britain’s intelligence arsenal. Flying over enemy territory, it was used to identify troop concentrations, manufacturing districts, communication lines, and the effects of bombing.

The RAF, less prepared for military intelligence than the Navy, took time learning how to understand photographic reconnaissance. It was focused on the land rather than the sea, resulting in reduced information for the Navy.

Worse, some senior figures in the RAF took an attitude of willful blindness to what the photos showed them, choosing to ignore evidence of the ineffectiveness of its bombing. It was an insight that OIC could have provided much quicker and forcefully.

Improvements Over Time

As the war progressed, the volume, variety, and quality of information improved.

At sea, convoy escorts were equipped with high-frequency direction-finding (HF/DF) equipment and Anti-Surface-Vessel (ASF) radar. It helped them to fight U-boats and provided information about them.

Back home, better analytical machines allowed more challenging codes to be cracked, contributing to the upkeep in the encryption war between code users and code breakers.

Improvements in photographic reconnaissance led to more information from this route.

Interrogation of POWs provided information about the capabilities of U-boats. With a better understanding of their speeds, supplies, and endurance, the analysts could better predict where the U-boats would go.

Such was the volume of information coming in that the Submarine Tracking Room was engulfed and Winn was forced to take a month off due to stress.

From before the Second World War, the Royal Navy were well equipped for military intelligence. As the war heated up, they gained the material to match their capabilities. Throughout, they remained among the finest analysts in military intelligence.

Source:

Ralph Bennett (1999), Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the War with Germany 1939-1945.