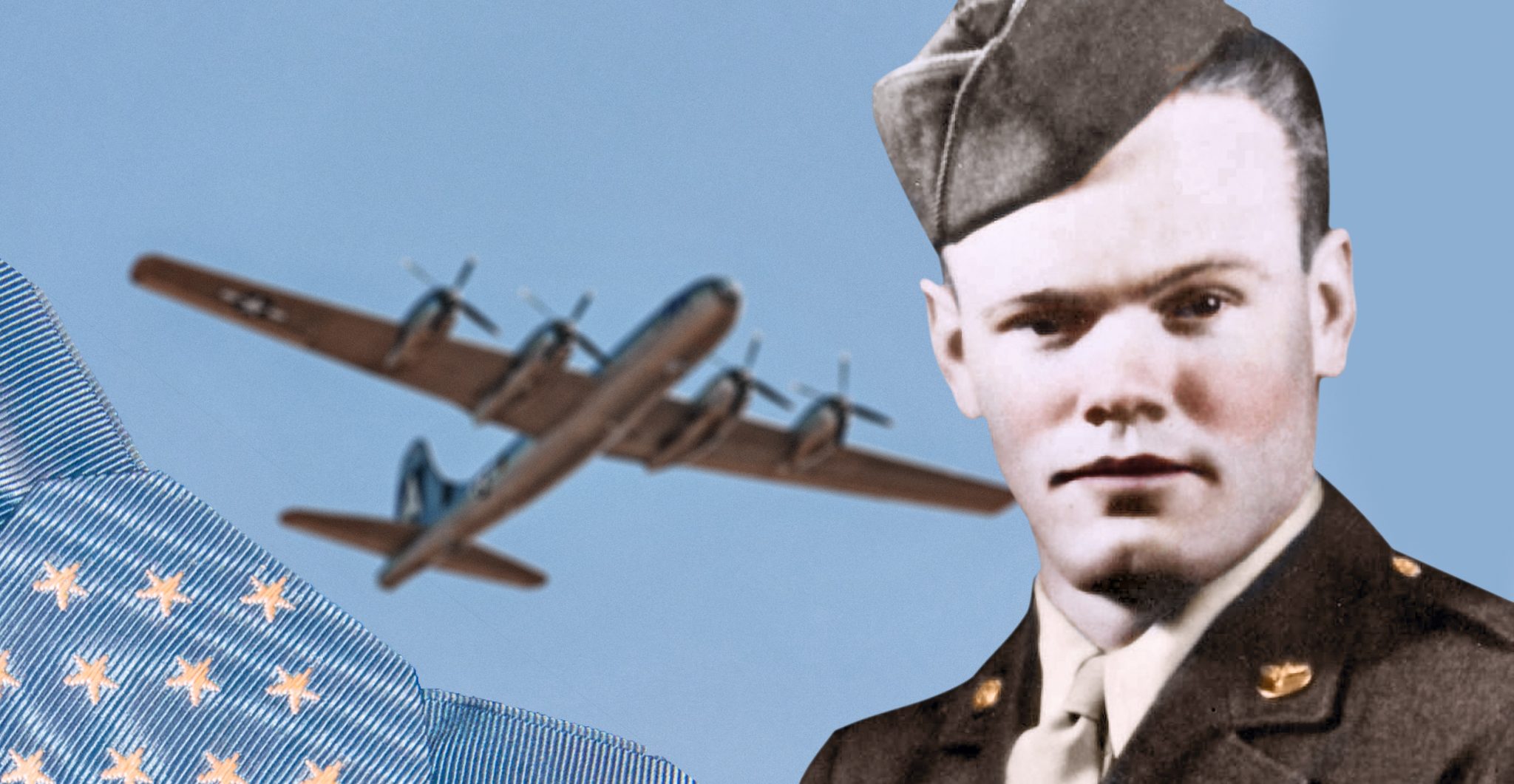

The Medal of Honor is America’s highest military award given to those for acts of valor that in some cases border on insanity. In WWII, one man earned his so fast; the military had first to steal it to give it to him.

Henry Eugene “Red” Erwin, Sr. was born on May 8, 1921, in Adamsville, Alabama to a large family. There was not a lot of money, made even worse ten years later when his father died. To help his family survive, Erwin started working and eventually dropped out of school for a full-time job at a steel mill.

In July 1942, he joined the Army Reserve at Bessemer. America had entered the war and so on February 3, 1943, he became an aviation cadet and trained to become a pilot in Ocala, Florida. Unfortunately, it did not work out as he had what was described as a “flying deficiency.”

He transferred to the technical school at Keesler Air Force Base in Mississippi as a private first class. His next stop was Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and then he went to Madison, Wisconsin where he trained to become a radio operator and radio mechanic.

He graduated in 1944 and became part of the 52nd Bombardment Squadron, 29th Bombardment Group, 20th Air Force based in Dalhart, Texas. During all this, he found time to get married. He got to enjoy marital bliss for three months only because, in early 1945, his squadron was sent to the Asia-Pacific Theater.

Based at North Field (today the Andersen Air Force Base) in Guam, their task was to bomb Japanese cities – sometimes unescorted by fighter planes. By April 1, Erwin was a decorated Staff Sergeant with two Air Medals to his name. They cannot have been enough as he would earn an even more impressive award later that month.

The City of Los Angeles was a B-29 Superfortress with a crew of 12, piloted by Captain George Simeral. Erwin was the radio operator, but he had other duties to perform as well.

On April 12, they were on their 11th combat mission – part of a large convoy heading for the Japanese city of Koriyama in Fukushima Prefecture. It was one of the longest trips they had undertaken from Guam, but Koriyama was important because of its high-octane and chemical plants.

They had to get as close as 500 miles from their target, making them vulnerable to enemy fighters and surface-to-air artillery. The City of Los Angeles was among the lead planes, followed by about 75 to 80 others.

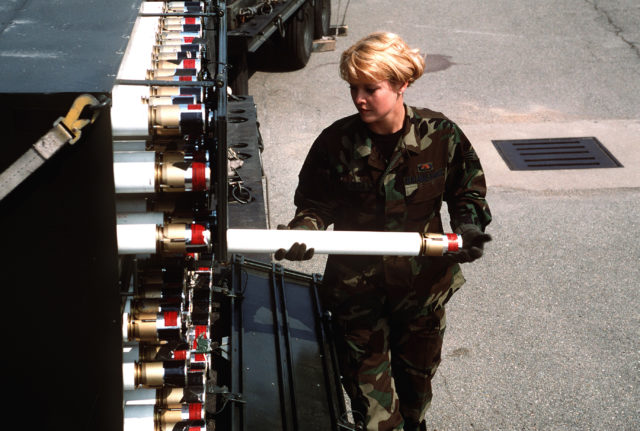

Once Erwin’s bomber reached the target area, his job was to drop phosphorous smoke bombs out the floor chute as a signal to the following planes. As their name implies, the bombs gave off a lot of smoke, as well as a tremendous amount of heat – about 1,100°. Once dropped, they explode in about eight to ten seconds.

Erwin was removing the bomb pins before dropping them when his life changed drastically. One of them was defective, which was why it exploded prematurely.

It zoomed back up the chute, into the plane, and straight into Erwin’s face – burning off an ear and blasting off his nose. Thick, white smoke immediately filled the interior, and the pilot could not see his controls or out the window. Simeral veered toward what he hoped was the harbor so they would have some chance of survival if they crashed.

Blinded, Erwin desperately crawled around looking for the bomb afraid it might burn through the floor and into the bomb bay below. They had only minutes before they either crashed or were hit by the enemy. An intensely religious man, Erwin called out, “Lord, I need your help.”

It came, but at a terrible price. As he groped around the floor, he found the bomb and picked it up. Despite the intense pain, he held it beneath his right arm against his thigh as he struggled his way to the cockpit.

There he found the co-pilot, Roy Stables, and yelled at him to open the window. Erwin chucked the bomb out and was rewarded when the smoke cleared, and visibility returned. Just in time, too.

They were about 300 feet above the water and descending fast. Finally able to see his controls, Simeral pulled up, saving everyone. Except for Erwin.

The bomb had burned his clothes away, and his flesh was peeling off. Surprised he had not yet passed out they gave him morphine. Instead of gulping down several, he took only a few. He had some medical training and knew that too much could kill him. Then he asked if everyone else was alright.

The City of Los Angeles aborted its mission and headed toward Iwo Jima – which the Allies had taken in February 1945. As phosphorous burns hotter with exposure to oxygen, more of Erwin’s flesh had burned off by the time they got there. It was so bad; they had to get him out through one of the plane’s windows.

The doctors did not hold out much hope for him. Major General Curtis LeMay and Brigadier General Lauris Norstad wanted to make sure Erwin received a Congressional Medal of Honor before he died. Obtaining the medal would take time – something the doctors were sure Erwin did not have enough of.

Fortunately, the military base at Pearl Harbor had one; in a display case. They rushed it to Guam, and formally presented it to Erwin on April 19. It worked.

He survived and was sent back to the US where he endured 41 operations in 30 months. He got his vision back, as well as the use of his right arm. In October 1947, they discharged him with the rank of Master Sergeant.

They also gave him the Purple Heart, the World War II Victory Medal, the American Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, the Distinguished Unit Citation Emblem, three Good Conduct Medals, and two Bronze Campaign Stars.