The Battle of Guadalcanal was one of the most important battles in the Pacific theater of World War Two. Marking the furthest expansion of the Japanese Empire, it was the place where the Allies turned back the tide.

Because of the prominent role of the United States Marine Corps in the battle, they are the Allied forces most often associated with the operation. But others played a vital part in the battle, and among them were the flyers of the Cactus Air Force.

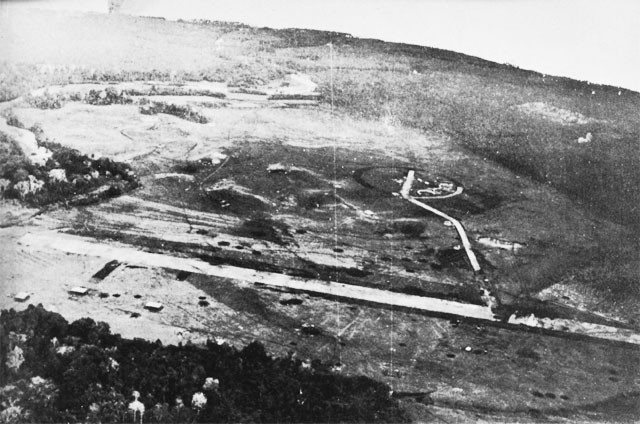

Henderson Field

The American invasion of Guadalcanal was a hurried business, rushed into action because the Japanese were building an airfield on the island. That airfield would give the Japanese a huge advantage in defending the island, as it would allow them to launch aerial attacks against incoming enemy ships, keeping troops from reaching the island, as well as allowing them to bomb and strafe any opposing forces that landed there.

Given its strategic importance, it was inevitable that the airfield would be one of the first targets for the Marines landing on Guadalcanal on the 7th August 1942. The airfield was captured in the first couple of days and became a key position in the fighting that filled the next few months. The Japanese repeatedly tried and failed to retake it, while the Americans used it to ferry supplies in and out when they found themselves cut off by sea.

The airfield was incomplete when the Marines arrived. Using equipment captured from the Japanese they brought it up to a sufficient standard for regular flights in and out. In the process they renamed it Henderson Field, after Major Lofton R. Henderson, a Marine Corps pilot killed during the Battle of Midway.

The Cactus Air Force

With the airfield operational, planes were moved in to provide air cover for the troops based on Guadalcanal. Their role was to deal with Japanese aircraft in the skies above the island and the surrounding straits so that supplies could be brought in and the soldiers could be protected from death from above. This ragged squadron became known as the Cactus Air Force.

Due to the circumstances of Henderson Field, the Cactus Air Force lacked even the most basic infrastructure upon which other flyers relied. With the Japanese lines so close to Henderson Field, there could be no fuel dumps or tankers. There were no repair sheds or bomb hoists. Ammunition was loaded by hand, and damaged planes were disassembled to provide spare parts. Even the airstrip was little more than dirt, turning to mud in the rain, hampering take-off and battering the aircraft.

How the Cactus Flyers Fought

Without the fuel supplies to keep up a constant air patrol, the Cactus Air Force had to use other tactics to get into the air before the Japanese struck. As a result, they were reliant on intelligence provided by other Allied representatives living in a dangerous part of the world.

Most of this intelligence came from Australian Coastwatchers. These were intelligence operatives based on the scattered Pacific islands, whose role was to keep an eye out for Japanese activity. Based in places such as Bougainville and New Georgia, they radioed in reports of incoming Japanese planes. This allowed the Cactus flyers to get into the air before the Japanese arrived.

Hit and run tactics were used to break up enemy formations, and so reduce the damage they could do. Focusing on the bombers allowed the Cactus Air Force to provide the best possible support for the Marines and naval forces, at great risk to their own lives.

Life, for the Flyers

Life at Henderson Field was miserable. Wet conditions and a lack of permanent buildings meant that the pilots and their crews were living in mud-floored tents, unable to escape the near-constant damp.

This weather brought huge problems with disease, for all the Allied troops on the island. Malaria, dysentery and fungal infections left men ill and incapacitated.

Then there was the ever-present threat of the Japanese armed forces. The line between the two sides lay close to the airfield, and the Japanese made repeated attempts to seize it from the allies, sending in banzai charges that were always fought off, but kept up the threat of being over-run.

Then there were the attacks by Japanese aircraft. Almost every day, a flight of Mitsubishi G4M bombers would soar over the field, dropping their explosive payload on the airstrip and the beleaguered Americans.

Finally, there was the Tokyo Express. Every night, Japanese ships would sail along the coast, bombarding the American positions. There was little protection against the threat of falling shells, and little chance to get a decent night’s sleep with guns roaring through the night.

Wildcats Versus Zeros

The fighting above Henderson Field was shaped by the planes the two sides flew.

The Japanese attacks came with fighter support from A6M Zeroes. These were light, fast, maneuverable planes with a good rate of climb.

The Americans, on the other hand, mostly flew F4F Wildcats. Not as fast or maneuverable as the Zero, the Wildcat was a better brawler. It was better equipped with guns, and better able to survive being hit. Its relatively sturdy construction and self-sealing fuel tank made it the tougher of the two planes.

Given the difference between them, the Americans could not beat the Japanese in extended dogfights, as they would be out-manoeuvred. Instead, they hit and ran, working in pairs to protect each other as they descended upon the Japanese from above, breaking away once they had done the initial damage. Whenever possible, they attacked the trailing edge of Japanese bombing runs, taking out planes at the rear before the rest could respond.

Despite difficult circumstances, the Cactus Air Force did great work in helping take and hold Guadalcanal. They claimed to have taken down 268 Japanese planes in two months, and this was earned in mud, blood and sweat.