For many generations, British sea power was a terrifying obstacle to any nation or empire who wished to oppose the might of those Isles.

In 1588, the Spanish sent a huge armada, loaded with tens of thousands of troops into the English Channel. But Queen Elizabeth’s small, desperate navy, with the aid of a miraculous storm, sent fireships into the tight formation of the massive fleet which had to squeeze together to fit it’s bulk into the Channel waters.

The great strength and pride of Spain was burned and smashed into the Cliffs of Dover.

For most of the 500 years after that event, the English Channel was unquestionably English. The Royal Navy, however, hung their heads in shame in the face of this great hubris after one of the most embarrassing encounters they had in the 20th century: the day some four dozen German ships, including two battleships, slipped right through the English Channel with barely a scratch.

The German’s called it Operation Cerberus and it went down in history as the Channel Dash.

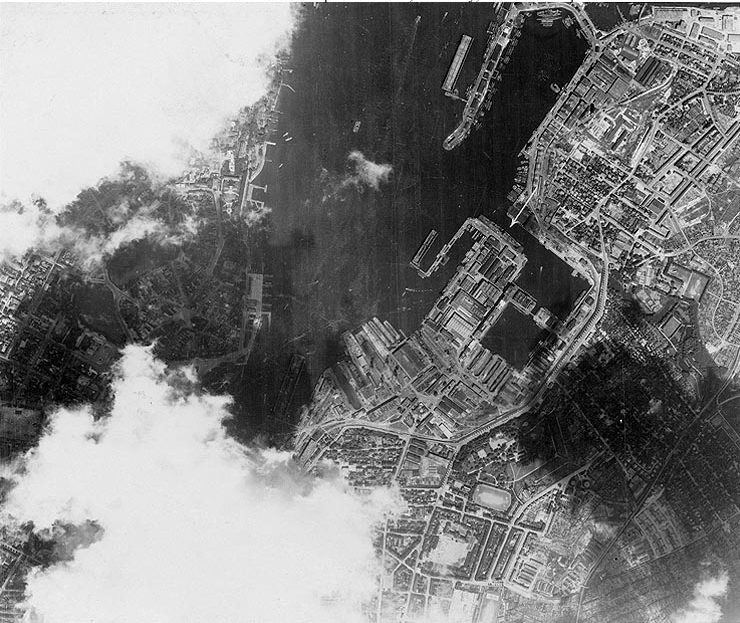

In early 1942, the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau (the only ships in their mutual class) and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen (which had taken part in Operation Rheinübung during which the Bismark was sunk by the Royal Navy in the Atlantic) rested under the naval flag of Nazi Germany in Brest Harbor, Brittany in Occupied France. Here, however, they were vulnerable to aerial assault from Britain and the Germans desired their presence further North to disrupt Soviet shipping lines.

The only question was how to sneak these ships past the Royal Navy and into home ports undetected and unharmed. Not even the Bismark, the largest battleship ever built, had made it past the British Isles without eventually being sunk.

The two possible routes for the ships to take were North and through the Denmark Straight between Greenland and Iceland or South, right through the English Channel. Upon Hitler’s direct orders, the second and far more risky option was taken.

Since April of the previous year, the Royal Navy had put a plan in place to foil just such a sneaky move by Hitler’s ships called Operation Fuller. The planned held that, if German ships like the Brest Group were detected moving through the Channel, it was the charge of Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay to take them out. Under his command for this situation, Ramsay had six destroyers on a four-hour standby in the Thames Estuary, three destroyer escorts, and 32 motor torpedo boats. This was to be complemented by support from the Royal Air Force and the Fleet Air Arm.

However, by the time Britain noticed the German ships moving through the Channel, almost no part of the plan was ready for execution and it was entirely bungled.

Vice Admiral Otto Ciliax, whose flagship was the Scharnhorst, sailed the two battleships and the heavy cruiser, escorted by six destroyers, 14 torpedo boats, and 26 E-boats, out of Brest late on the night of February 11th, 1942. For days, the Germans had been slowly increasing their radar jamming activity, so this could happen unnoticed.

The British had also assumed that any German ships attempting to sail through the narrow, East side of the Channel at Dover-Calais would wish to do so at night to hide from the British coastal batteries it was required to pass within range of. The Germans, however, valued the several hours of undetected travel at night prior to reaching the batteries, favoring the element of surprise.

Along with planes flying diversionary missions like bombing Plymouth Harbor, the Luftwaffe also assigned 32 bombers and 252 fighters to cover the ship’s mission in shifts. The British, using radar frequencies the Germans hadn’t detected, noticed the large uptick in enemy air activity over the channel. When a pair of RAF Spitfires when out to investigate, the German fleet was discovered, and the game was afoot.

At this point, it was past 10:30 AM and the German ships were already most of the way through the Channel. The Royal Navy destroyers and escorts assigned to counter this bold run were far from prepared.

The first shots fired on the German ships were from the coastal batteries in Dover at noon on February 12th. Using the radar frequencies unknown to the Germans, the operators were able to detect the ships, but with the targets zigzagging to avoid the shells and sailing far out of direct line-of-sight, not a single ship was hit.

A 14-inch British coastal battery gun near the cliffs of Dover

The next Brits to engage came in on five motor torpedo boats, but were blocked by the large flotilla of E-boats and turned around without scoring a hit. Like everything else about the British plan for this scenario, the RAF cover for these ships wasn’t ready yet either and didn’t make it in time.

Eventually, the RAF got themselves together and sent out well over 600 aircraft throughout the day to intercept the Brest Group. However, due to the German’s radar jamming, low, dense cloud cover, and rain, only a small fraction of the planes even found the enemy. Only 39 of the 242 bombers sent out that day engaged the ships and never even damaged one.

The most courageous action of the day, according to both sides, was that of Lieutenant Commander Eugene Esmonde and his detachment of six Fleet Air Arm Fairey Swordfish Biplanes. They were totally out-classed, out-gunned, and out-numbered, but raced at the enemy ships and aircraft nonetheless. All were shot done before hitting anything, and only five of eighteen airmen survived.

Ciliax, taken by the sight, later wrote, “…the mothball attack of a handful of ancient planes, piloted by men whose bravery surpasses any other action by either side that day”.

Finally, the six destroyers assigned to intercept the Brest Group, who had been engaged in gunnery practice in the North Sea, arrived to offer their woefully inept and useless contribution. They fired one volley of torpedoes and missed with every last one. Return fire from the Gneisenau and the Prinz Eugen struck the HMS Worcester, killing 26, wounding 45, and severely damaging the craft.

Overall, the most significant damage done to the Brest Group was by mines hit by the two battleships on their voyage home. Both Britain and Germany lost a few dozen aircraft. From start to finish, it was an incredibly embarrassing moment for the Royal Navy.

Wikipedia quotes an editorial from The Times of London on the event saying, “Nothing more mortifying to the pride of our seapower has happened since the seventeenth century. […] It spelled the end of the Royal Navy legend that in wartime no enemy battle fleet could pass through what we proudly call the English Channel.”

By Colin Fraser for War History Online