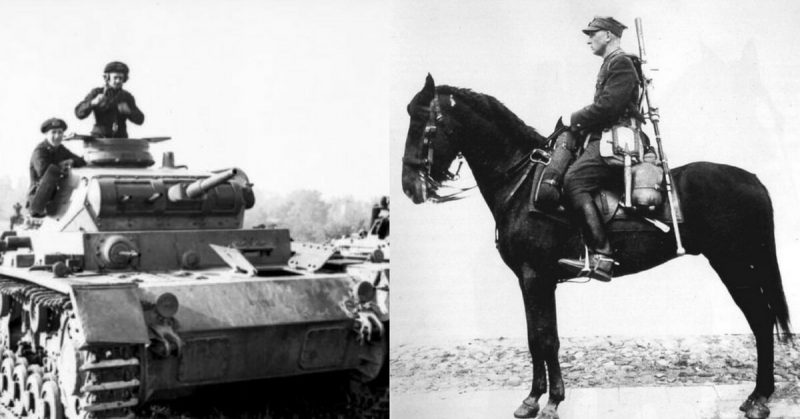

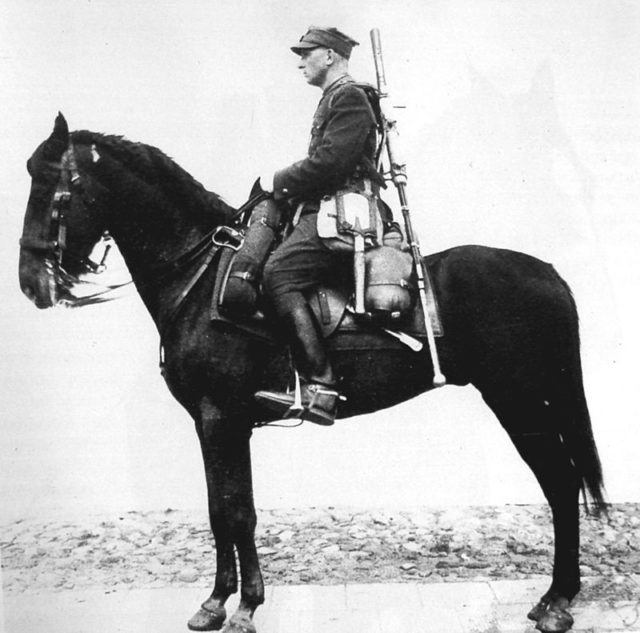

Poland had a long history of horsemanship, and its light cavalry called Uhlans (Tatar word for “Hero”, or “Rider”) were the pride of its army. When Hitler invaded on 1st of September, 1939, he swept across Poland with a different kind of cavalry ― tanks. The whole world watched the dawn of entirely different warfare. No more were the horsemen lords of war in the flatlands of Eastern Europe, but mere cannon fodder.

Before all hell broke loose, it was obvious that the Germans were aiming to end Polish sovereignty. The Free City of Danzig, established by the Versaille treaty, was a semi-autonomous territory that acted as part of the Polish state. Part of the initial battles of the invasion was the famous cavalry charge at the village of Krojanty southwest of Danzig. This was where Hitler struck first.

At the same time, from the east, the secret part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact took effect. The Soviet Union invaded the country, causing a complete collapse of Polish attempts to defend themselves. While the Germans were practicing Blitzkrieg, the Poles were cornered and forced to fight to their death. Even though the Polish High Command had initial success, the enemy was far better equipped and larger in numbers. The Poles relied on courage as their last resort. It all came down to heroic acts of individuals.

Thus, the Charge at Krojanty turned into a modern myth. The basis for the myth is true, as Poles did use cavalry extensively during their desperate defense attempt against the Germans, but the story later evolved into a propaganda effort by both sides.

The truth is, the Polish Cavalry did see extensive combat, and was able to rout the enemy infantry units on several occasions, but the mythic component was the story that the Poles charged the German Panzers, believing they were dummies. Now, why would they believe such a thing?

The answer lies in the restrainments of the Treaty of Versaille from 1919, which explicitly prohibited the use of tanks by the German Army. Hitler violated this agreement, but the Poles refused to believe it.

The Battle of Krojanty happened on September 1st, as part of the much larger Battle of Tuchola Forrest. This was a series of skirmishes across the Polish defense line in the countries northwest. Krojanty, a small village in northern Poland, which was under the jurisdiction of the Free City of Danzig, became the field of battle which later turned into a story for future generations.

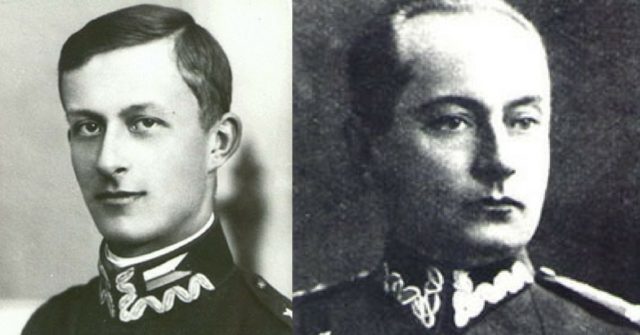

The 18th Pomeranian Uhlans spotted a group of German infantry resting at a railroad near the village. Colonel Kazimir Mastalerz, the commander of the Uhlans, ordered Eugeniusz Świeściak, commander of the 1st Squadron, to use the element of surprise. He was ordered to charge at the Germans, with his horsemen, who were mostly equipped with lances. The two other squadrons, which included the TKS/TK-3 tankettes as support, were held in reserve.

The initial charge proved to be successful. The German infantry dispersed as the Uhlans chased them across the field. But then, German armored vehicles (most likely Leichter Panzerspähwagen or Schwerer Panzerspähwagen) joined the fight, advancing through the nearby forest. They fired a machine gun barrage which decimated the Polish horsemen. Commander Świeściak was gunned down. Colonel Mastalerz hurried to his aid, prompting the second two squadrons to advance. He was killed soon after by the same armored vehicles.

The battle ended, and German and Italian war correspondents rushed to cover the story. As they saw the dead horsemen, they immediately concluded that the charge took place against the German armor. The Italian journalist, Indro Montanelli, wrote on that day about the bravery of Polish Uhlans who charged the German tanks with lances and sabers. This article was the initial point of the myth.

A third of Polish force was either dead or wounded after the Battle of Krojanty. Even though the battle was lost, it enabled the Polish 1st Rifle Battalion and National Defence Battalion Czersk to execute their tactical withdrawal from the nearby village of Chojnice. The charge left an impression on the Germans, as they ended their advance for the day. The self-confident and arrogant German officers were indeed frightened of the Uhlan’s cavalry charge, as they managed to disturb the Wehrmacht’s advance on several points along the front.

The Poles were able to outmaneuver the German Panzers, and strike the supporting infantry from the rear, leaving the tanks unguarded. On 15 different occasions, the Polish Uhlans managed to stage charges, cover the retreating friendly units and cause panic and confusion within the enemy. Even though the lance stopped being part of the official cavalry arsenal in 1937, it was still available as a weapon of choice. The traditional long spear was often decorated with a small Polish flag and was thus seen as a motivation tool, besides from being an effective weapon against infantry.

After a month of fighting, Poland fell to its conqueror. The Nazis wanted to mock the defeated Poles by further developing the propaganda myth which incorporated suicidal charges of Polish cavalry on German tanks. They also wanted to point out how superior the German people were in compared with primitive Poles who still used horses in battle even though the time of cavalry had certainly passed.

The Poles saw the myth as part of their mentality ― bravery against all odds, and adopted the story proudly and defiantly. The myth survived the war and was used as Soviet propaganda to discredit the pre-war Polish officers who, allegedly, wasted the lives of their soldiers. As late as the 1990s, this story was still taught in history classes in American high schools and colleges.

Nevertheless, the story remains inspirational as it depicts romantic bravery against a far superior enemy. A Nobel Prize winning author, Gunther Grass, was particularly struck by the news of the Poles charging the German tanks. He wrote in his famous 1959 novel, “The Tin Drum”:

O insane cavalry… with what aplomb they will kiss the hand of death, as though death were a lady; but first they gather, with sunset behind them – for color and romance are their reserves – and ahead of them the German tanks, stallions from the studs of Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, no nobler steeds in all the world. But Pan Kichot, the eccentric knight in love with death, lowers his lance with the red-and-white pennant and calls on his men to kiss the lady’s hand. The storks clatter white and red on rooftops, and the sunset spits out pits like cherries, as he cries to his cavalry: “Ye noble Poles on horseback, these are no steel tanks, they are mere windmills or sheep, I summon you to kiss the lady’s hand”.