The USS Indianapolis (CA-35) was a Portland-class heavy cruiser commissioned by the US Navy in 1932. She was the flagship of Scouting Force 1 prior to the Second World War, and eventually became the flagship for Adm. Raymond Spruance of the US Fifth Fleet. On the day she went down, Indianapolis was under the command of Capt. Charles McVay III, who wound up being blamed for her sinking. It took 50 years, and an unlikely helper, for his name to be cleared.

Sinking of the USS Indianapolis (CA-35)

During the Second World War, the USS Indianapolis served throughout the Pacific Theater. Her final mission was to deliver top-secret parts for the atomic bomb Little Boy to Tinian Naval Base. On July 30, 1945, the cruiser was traveling from the base to the Philippines for training duty when she was torpedoed by the Japanese submarine I-58.

The hit caused Indianapolis to sink in just 12 minutes. Roughly 300 crewmen went down with the ship, while the remaining 890 were stranded in the water. Not only did they have to deal with normal concerns – dehydration, exposure and exhaustion – they were also attacked by a shiver of sharks that were drawn to the bloody water. Initially, the fish attacked only the dead, but quickly became less selective.

Despite sending out numerous SOS signals, it took four days before the US Navy found the survivors, then numbering only 316.

Charles McVay III and the loss of the USS Indianapolis (CA-35)

Charles McVay was one of the men rescued after the sinking of the USS Indianapolis. He was livid that it had taken so long for help to arrive, but was never given a concrete answer as to the delay. The service claimed the SOS messages were never received, despite declassified records later showing that three of them had actually gone through. They were ignored for different reasons: a drunk commander, orders to not disturb and the belief one was a ruse by the Japanese.

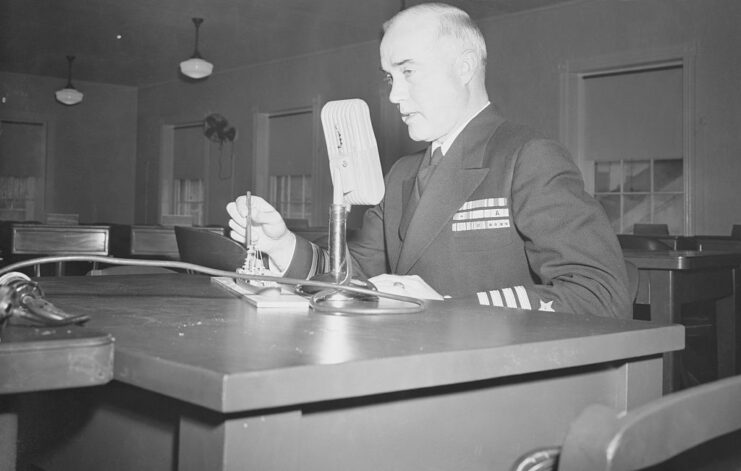

As the senior officer onboard the ship, he was court-martialed for what happened, despite Adm. Chester Nimitz‘s feeling a letter of reprimand would be enough. McVay was accused of failure to order the abandonment of Indianapolis in a timely manner, as well as failure to zigzag. He was charged for the latter, despite testimonies that this tactic was barely effective, which included one from Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) Cmdr. Mochitsura Hashimoto of I-58.

As if this decision wasn’t controversial enough, there was significant information available that showed Indianapolis was placed in a dangerous position not by McVay, but by other admirals. The captain had asked for destroyers to escort the vessel, a request that was denied, even though the area was known to contain Japanese submarines. This decision also meant Indianapolis was sailing blind, without submarine detection equipment.

A heavy burden to bear

Out of hundreds of US ships sunk during World War II, Charles McVay was the only captain to be court-martialed. Although the decision was eventually overturned by Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, and McVay later promoted to rear admiral, his career in the Navy was all but over, as he struggled to get over the treatment he’d received after the USS Indianapolis sank.

He officially retired in 1949, but this wasn’t enough to distance him from the incident. The families of those who perished in the sinking reacted in a variety of ways. Some didn’t blame the McVay, while others did. The latter went so far as to send him letters with horrible statements, like, “Merry Christmas! Our family’s holiday would be a lot merrier if you hadn’t killed my son.”

Eventually, the burden became too great, leading McVay to take his own life on November 6, 1968. He was found at his home in Connecticut with his pistol in one hand and a toy sailor in the other. The latter had been a gift from his father.

Hunter Scott to the rescue

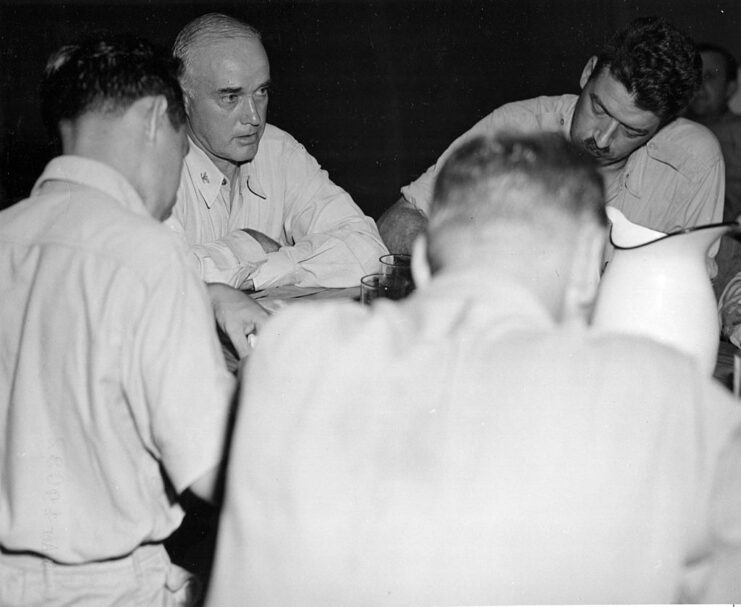

Sadly, Charles McVay didn’t live to see his name cleared, which it eventually was, thanks to the efforts of Hunter Scott. No, he wasn’t an expensive lawyer or professional researcher – he was a sixth-grade student who researched the sinking of the USS Indianapolis for a school history project. He interviewed nearly 150 survivors and consulted over 800 additional documents to conclude that McVay had been wrongfully charged.

Scott didn’t stop with just his school presentation. He brought his research to the attention of Congressman Joe Scarborough (R-FL), who helped him take it before the US Congress. His research was monumental, resulting in a resolution, signed by President Bill Clinton in 2000, that exonerated McVay.

He went on to join the Navy himself, serving aboard USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6).

More from us: SS Normandie: The French Ocean Liner Lost to a Suspicious Fire During World War II

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

Scott said during his impassioned speech to Congress:

“This is Captain McVay’s dog tag from when he was a cadet at the Naval Academy. As you can see, it has his thumbprint on the back. I carry this as a reminder of my mission in the memory of a man who ended his own life in 1968 […] I carry this dog tag to remind me of the privilege and responsibility that I have to carry forward the torch of honor passed to me by the men of the USS Indianapolis.”